I got to know one of the great Yankees from their dynasty years in the 60s during the two years former third baseman Clete Boyer was a coach with the Columbus Clippers. He, and I, made the most of it.

Columbus – There is an underrated movie that ran in theaters in 1982 titled My Favorite Year, starring Peter O’Toole, Jessica Harper, Joseph Bologna and Lainie Kazan and one of the all-time exceptional character actors, Selma Diamond.

Columbus – There is an underrated movie that ran in theaters in 1982 titled My Favorite Year, starring Peter O’Toole, Jessica Harper, Joseph Bologna and Lainie Kazan and one of the all-time exceptional character actors, Selma Diamond.

The scene is 1954 and a Jewish kid from Brooklyn by the name of Benjy Stone is a go-for for the fictitious NBC variety show “The King Kaiser Show.’’

Stone’s all-time favorite movie hero Alan Swann, a swashbuckling Errol Flynn facsimile from the silent movie era, has been signed to do a couple of skits with Kaiser.

Veteran columnist Mark Znidar writes the Buckeyes for Press Pros Magazine.com.

It’s Stone’s job to baby sit Swann long enough for everyone to get the show done without any disasters.

We won’t go any farther into the plot other than to write that Swann is a fall-down drunk and has had great difficulty staying relevant in the early stages of the boob tube.

There is a happy ending and it’s a delightful 1 hour, 32 minutes, especially if you grew up in that decade or was a child of the ‘60s and heard stories from parents and relatives about the early days of television.

My favorite years were 1990 and ’91…when the New York Yankees assigned Clete Boyer to be the Columbus Clippers third base coach. To this day, his stories and inside information from those glory days are like gold bullion.

The introduction came during spring training in Tampa when Boyer asked who in the heck I was, shook my hand and invited me to a players-only barbecue on a Sunday. The Casey Stengel Yankees did not approve of Boyer getting so buddy-buddy with writers, but he did it anyway.

He told me that we probably would be among the few English-speaking people in attendance. Then he explained that the many Latinos in the organization – we’re also talking double-A and single-A players – couldn’t read menus in restaurants and didn’t eat well.

Boyer was traded to the Braves in 1966 after the Yankee dynasty was gone…and the Braves needed a big-name third baseman to replace Eddie Mathews.

What Boyer did was have his grill transported from his home from the suburban Atlanta area to the ballpark at his expense. He bought pounds and pounds of pork and fixings. Of course, there was Budweiser – lots of Budweiser – because he stayed loyal to St. Louis, the city where he was raised..

Until that time, I looked at minor league managers and coaches as mostly colorless, humorless men trying to get through the grind. That excludes the upbeat Sammy Ellis and the original good old boy, Charlie Manuel.

There was never anyone quite like Boyer.

I got to know Clete better when he’d hop rides in my rental car when the Clippers would travel from Richmond to Norfolk, from Rochester to Syracuse and from Pawtucket to Scranton/Wilkes-Barre. He was spoiled from his Yankees days and thought buses were beneath him.

He never made more than $800,000 during his big league career that started in 1955 with Kansas City and ended in 1971 with Atlanta, but the man was charitable to the hilt.

On the way to the team hotel in Norfolk, Boyer spied a K-Mart and burst out, “Let’s go there. Let’s go there.’’ The immediate thought was that he forgot to pack a toiletry.

“I’m going to buy some underwear for my boys and it’s on sale,’’ he said.

“Wait,’’ I said, “you have a son and daughter.’’

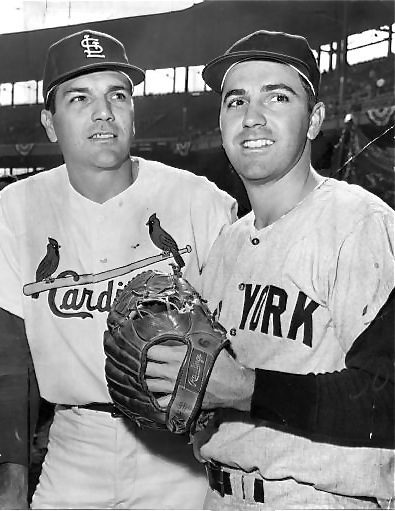

He played against his brother Ken in the 1964 Yankees-Cardinal World Series. They each hit a home run in game 7, the first brother duo in history to each homer in a World Series game.

His boys happened to be Graig Nettles, Rollie Fingers and Cesar Cedeno. He managed them in the long defunct senior league that played out during the winter.

“Those guys should all be set financially,’’ I told him.

“All of those guys you mentioned are broke,’’ he said.

When the 1991 season was winding down, Boyer took broadcaster Terry Smith, traveling secretary Mac McComb and me to a restaurant called ‘Mama Mia’s’ in Massachusetts, just across the border with Rhode Island. The club was in Pawtucket for a series.

We were told to order anything and everything on the menu. He bought expensive wine and, of course, Budweiser. He’d frown if you ordered Miller or Coors or anything else. We dined like royalty.

The waitress brought the check and I grabbed for it. Boyer clutched a wrist and squeezed pretty hard.

“What do you think you are doing?’’ he said. “This is on me.’’

I told him I wanted to put down the tip.

“I just got paid $10,000 cash to sign autographs for a couple of hours,’’ he said. “This isn’t going to break me.’’

Boyer brought alive the era of the ‘50s and early ‘60s in baseball for me that up until then consisted of grainy black and white highlights.

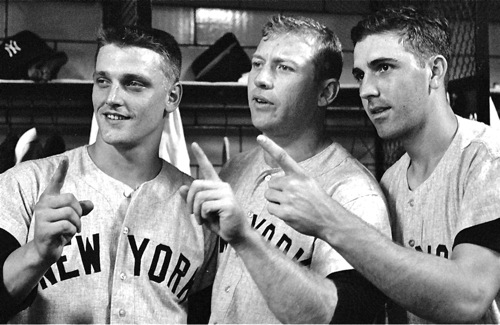

Boyer once told me that the Yankees would go into every game thinking they were going to win. They considered trips to Cleveland and Kansas City like practice games. Mantle, Whitey Ford, Billy Martin, Yogi Berra and Roger Maris, he said, always knew when opponents were intimidated and went for the easy kill.

Documentaries and books have revealed at length that Mantle partied hard because he thought he’d die early like his father. Boyer said Mantle also drank heavily because his legs were shot long before he turned 30 years old and was in great pain on a daily basis.

Maris went on to become a distributor for Budweiser, but wasn’t a drinker. In 1961, he did hit 61 home runs and was voted American League most valuable player, but New York was the worst city in baseball for this introvert.

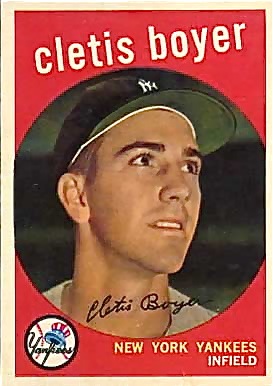

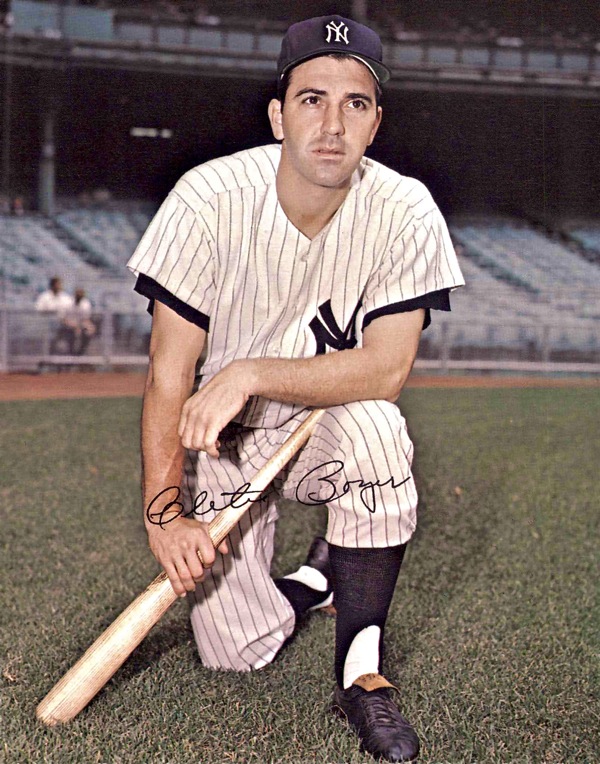

Boyer on his first Yankee card after his trade from Kansas City in 1959.

What you read and see in the documentary on ESPN about Billy Martin is true. Sober or drunk, he would brawl if a teammate or, yes, marshmallow salesman looked at him the wrong way or made a snide comment.

Every single day was war for Martin because he grew up deprived and tough in Oakland. Ballclubs said he’d never make it because he was too skinny and too short. He proved them wrong because of rage stemming from those criticisms.

When he was a coach with Oakland in the 1980s, Boyer said Martin often wouldn’t show up for games until shortly before the national anthem because he was at a bar or with a woman, or both.

Whitey Ford, Clete said, was everybody’s friend. He was crafty on the mound, witty in the clubhouse, and kept many bars in the green. His strength was that no moment was too big for him.

Boyer said catcher Elston Howard was the one player on the roster who acted his age. He was a class act. Clete didn’t care for Berra, saying he was cheap and went his own way after games.

No one could put the alcohol down like Boyer. He once autographed two or three baseball cards – he knew I was a collector – before a game. I told him he ruined one card by autographing directly over his face.

“That was a bad card,’’ he said. “The photographer showed up on a morning that I was hung over. I look terrible, so I sign my face.’’

Boyer’s philosophy was that the baseball season took so much out of a player, coach, and manager that alcohol was needed to diminish the stress and pain.

The players were dreading a 5 a.m. wake-up call the morning after the Clippers played extra innings at Pawtucket. It was about midnight when everyone got back to the hotel.

Ah, but I didn’t make it back to the room until 2 a.m. We had only a few beers because it was so late.

Boyer kept telling me that everyone on the team was going to feel crummy whether they had alcohol or water, and four hours sleep or none.

The next morning, Clete was smiling sitting on the bus. He was wearing sunglasses to hide what amounted to sleeping bags underneath his eyes.

“How do you feel?’’ he said.

“Pretty good, actually,’’ I replied.

The glory years…Yankee greats Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle, and Clete Boyer as the Yankees won five pennants and two World Series from 1960-’64.

Then Boyer pointed over one shoulder and to second baseman Andy Stankiewicz. Stankiewicz was ultra-religious. He didn’t drink, smoke or run around looking for women. There was no tougher man on game day and no better teammate.

Stankiewicz looked beat that morning.

“Hey Stanky,’’ Boyer said, “how do you feel?’’

“What do you think I feel like?’’ Stankiewicz said.

Clete looked at me and said, “See, I was right.’’

Translation: Sleep is overrated.

One spring training, players and coaches kept asking Boyer how he had lost so much weight during the off-season.

His reply: “Budweiser and Slimfast. That’s all you need.’’

Boyer was a fatalist, but he did fear for his safety one morning when the pilot of our jet aborted a take-off at Port Columbus.

The pilot got on the intercom and said he didn’t like the readings of one of the gauges or something like that.

Boyer clearly was shaken. It was a panic stop that few experience.

“Why didn’t he just say we forgot the damned coffee?’’ Boyer said.

It got worse for him.

A player several rows behind said, “Hey, Znidar, what would the headline be if the plane went down?’’

Before Boyer could respond, the player said: “Former Yankee great Boyer killed in plane crash. One hundred or so other people also die.’’

He was charming on those flights. A pretty aging woman obviously had an eye for him and started a conversation by asking why he used lip balm constantly when it was summer.

“Because you never know when you are going to use them,’’ he said, winking.

She became flustered and turned around in her seat. Her husband didn’t have to worry about any further conversation.

I must write a Bob Uecker story that I have retold hundreds of times.

In 1966, Boyer was traded to Atlanta when the Yankee dynasty was over and the club was rebuilding. The Braves wanted a big name to replace Eddie Mathews and to develop the fan base after the move from Milwaukee.

In 1966, Boyer was traded to Atlanta when the Yankee dynasty was over and the club was rebuilding. The Braves wanted a big name to replace Eddie Mathews and to develop the fan base after the move from Milwaukee.

It’s common for bars and restaurants to comp big league players’ food and drinks merely to have them hang around in order to draw fans.

One night, the owner of the bar that Boyer and Uecker frequented had to take an urgent call in the back room. He asked Uecker if he would pour drinks until he returned.

“I always wanted to do this,’’ Uecker said.

The owner returned to see a jam-packed building and people clawing for drinks.

“This is great,’’ he said to Uecker. “But where are you putting the money?’’

Uecker looked at him with a straight face and replied, “I’m just pouring the drinks. You didn’t say anything about taking money.’’

The barkeep lost hundreds that night, but the flip side was that business exploded from that point.

The Koverman-Staley-Dickerson Agencies remind everyone to stay positive and be safe during the current Covid-19 emergency.

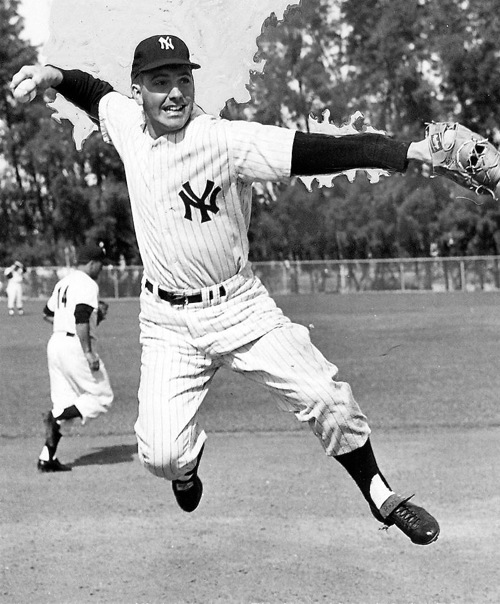

Boyer was a character, but he sure could play. He won one Gold Glove and had to go to the National League to get it in 1969. You see, Baltimore’s Brooks Robinson won the award every single season. Boyer led the league in defensive WAR two seasons and was in the top 10 seven other times. He played in five World Series, getting a winner’s share in 1961 and 1962.

When he showed the Clippers video of his fielding gems in the clubhouse, one snarky question from one player was why didn’t he field more balls cleanly.

Boyer excused himself to go to the coaches’ office and brought back one of his old gloves.

The players then started asking him how in the world could he field with leather that small.

The fictional Benjy Stone has nothing on me. He had Alan Swann for a couple of days. I had Clete Boyer for two seasons. I am better for it.

Clete passed at age 70 in 2007 in Lawrenceville, Georgia. No one packed more into a life than he did.

(All quotes in this story are paraphrased, but as accurate as I can be almost three decades after the fact. I think Clete would approve.)

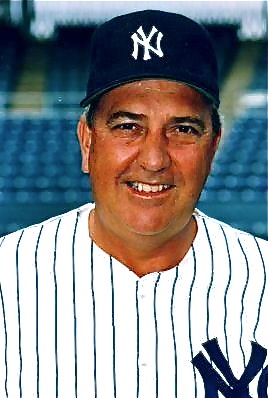

He was a lifetime .240 hitter. Clete Boyer made his money with his glove, but it took a trade to the National League (Braves) in 1966 for him to finally win a gold glove award. (Press Pros File Photos)