Looking back I could have been bitter, like some others, but I’m not. I remember my last baseball game – my last game as a Buckeye – with the satisfaction of having done all I could do with the tools I had…and maybe too much!

It made me stop and take note. Earlier in the summer, while looking through the Ohio State baseball archives for some other details, I saw the schedule and record for the 1974 season, my last as a Buckeye. My last season as an actual baseball player.

It made me stop and take note. Earlier in the summer, while looking through the Ohio State baseball archives for some other details, I saw the schedule and record for the 1974 season, my last as a Buckeye. My last season as an actual baseball player.

I remember three things, specifically, about that season.

One, after finishing tied for third in the Big Ten the year before with a 22-14-1 record, we dipped, and dipped badly in 1974…to 14-24 overall, and just 6-12 in the league.

Two, I remember excruciating pain trying to throw the ball after suffering an arm injury the previous year, my junior season. Back then it was just a sore shoulder, but in modern medical terms I know now that I had a torn rotator cuff.

Pain? It felt like an ice pick going through my brain when I tried to throw a baseball. And yet, given a diagnosis of a “strain” I tried to pitch through it, oblivious to the fact of what I didn’t know.

I didn’t pitch much my senior year. The coaching staff, the ageless Marty Karow and pitching coach Dick Finn, had recruited new, hard-throwing arms to the program and were giving those young guys every opportunity to get their sea legs as quickly as possible.

I, on the other hand, was just trying to throw something that moved…and that didn’t hurt.

A graduate assistant coach, Jon Warden, who had pitched for the Detroit Tigers on their ’68 World Championship team, spent a lot of time showing me how to apply a certain substance on the baseball, and letting the ball slide off my fingers with a forward spin it would dip dramatically by the time it got to home plate. Why not, I reasoned? A number of big league pitchers were doing it with apparent success.

My last start as a Buckeye, a 7-5 win over Michigan State in May, 1974.

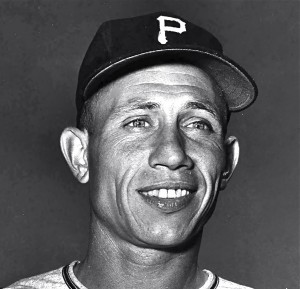

Former Pittsburgh Pirate Harvey Haddix was a good friend of my high school coach, Jim Hardman. They grew up together outside Springfield, and Hardman caught Haddix as a Clark County amateur. Haddix showed me how to ‘nick’ the ball with a metal eyelet on my Wilson A2000…to create wind resistance and added movement. “This will help the ball sink,” Harvey said. “No one will ever suspect in college baseball.”

I had started one game early in the year, lost badly, and never got the call again. That is, not until the next-to-last weekend of the season when a very good Michigan State team came to Columbus for a Saturday double-header and beat us up pretty good in the first game. We ran short of pitchers, and Dick Finn told me in the fifth inning that I would be getting the ball for the second game.

“Go as long as you can,” he said bluntly. “We don’t have anyone to help you.”

Marty Karow had been the coach at Ohio State since 1951, had won the national title in 1966, and frankly, was holding on for as long as his health would allow him to continue as head coach. A heart attack three years prior (that none of knew about) had seriously hampered his physical mojo.

Karow and I had locked horns on a couple of occasions. He didn’t like my playing in the Ohio State marching band in the fall, rather than showing up for fall baseball; but fall baseball then was nothing like fall baseball at Ohio State is today.

And, he didn’t respect that I didn’t throw all that hard, just 87-88 miles per hour by today’s measure. But, I threw breaking balls with more accuracy than anyone else on our pitching staff. And even though I led the team in innings, in strikeouts, and wins my sophomore year, Marty wasn’t satisfied because I didn’t throw, in his words, “Big Ten hard”.

Former big leaguer Harvey Haddix, from Springfield, taught me how to get some extra movement on the fastball.

He particularly didn’t like Warden teaching me alternative ways to pitch. As he watched me work out one day early in my senior year, my new ‘sinker’ was really diving.

“How the hell are you doing that?” he demanded.

Without thinking I admitted to what I was doing with the baseball.

“I’ll not have that on this team,” he stormed. “You either do it my way…or you don’t pitch.”

Except in that Saturday double-header against Michigan State. Doing it his way the Spartans scored five runs in the first before I ever recorded an out. Frustrated, and with no one to replace me, Karow came to the mound and said to catcher Terry McCurdy, “He doesn’t have a thing, Mac. If I were you two,” he paused, “I’d throw that good sinker you’ve been working on.” Marty never once looked at me as he left the mound.

But McCurdy and I looked at each other like we had been given the answers to the test. Eight pitches later we were out of the inning; and seven innings later the Buckeyes had come back from that early deficit to score a 7-5 win. Marty came to greet me with a big smile as I walked off the field with a big smile and pounded me on the back as we walked to the locker room in the North Athletic Facility.

The third thing that I remember was the week following that win over Michigan State. We were traveling to Indiana to finish the year and I had hoped that I might get at least one more chance to pitch, given my success against the Spartans. My optimism was heightened by the fact that following that game Karow had joked and told reporter Kaye Kessler that “every trumpet player in America was proud of me.”

But on Monday Karow didn’t even speak to me at practice. And I wasn’t asked to throw on the side, our normal weekly routine – not even live batting practice. On Wednesday Dick Finn took me aside and awkwardly said, “You’re going on the trip because it’s your final weekend, but you won’t be pitching.”

This is a pretty good example of sports at the next level – what I sometimes tell high school parents obsessed with the idea that sports, and life, should be fair and equitable. That’s a nice sentiment, but hardly reality. You don’t question playing time in college.

I remember that final trip as being rather somber. We didn’t play well in the first game of a Saturday doubleheader, and as I stood at my locker tucking in my shirt prior to the final game of the series Karow walked up to me. We were the only people left in the locker room.

The immortals of Ohio State baseball are honored on the outfield wall – left to right – Fred Taylor, Steve Arlin, Bob Todd, and Marty Karow.

“I want to explain something to you,” said Karow. “You deserved that game last week. You’ve been a good player for me for four years and you gave me all you had.

“But we’re not going to use you today because you can’t do it the way I want. You know that, and I know it. You’ve tried. But not anymore. I wish you the best, whatever you do.”

I had no words, just contempt. I don’t even remember the final outcome, but we must have won the second game because I remember the bus ride back to Columbus as being better than the trip to Bloomington.

I remember going to the North Athletic Facility for one final time on Monday, to clean out my locker, turn in my stuff…and one last long look at #6, my uniform shirts, home and road.

Marty never showed up as we all hurried to get done, and I didn’t take it upon myself to look him up to say goodbye. I went to my car, turned out of the parking lot, and headed for home – to Piqua.

At about Plain City, driving west on route 161, it hit me. The finality of playing baseball for the last time…the pride of being a Buckeye…of winning a handful of games in four years…and truly, as Karow had admitted, of giving it all I had.

At about Plain City, driving west on route 161, it hit me. The finality of playing baseball for the last time…the pride of being a Buckeye…of winning a handful of games in four years…and truly, as Karow had admitted, of giving it all I had.

For year afterwards I thought about that day, that and the fact of being told I wasn’t ‘Big Ten’ good, a sentiment felt by more than one of my teammates who left after the ’74 season. It was a hard lesson – bitter to swallow – and when I learned that Karow had died a decade later my only memory was of that icy stare the last time we spoke.

I never forgot, and over the years the reality has served me well. I ran out of time at Ohio State, but in the real world I quickly learned the importance of getting back up when you get knocked down. Get back up and do it better.

It was the only way then, and it’s the only way now. No need to complain, and no recourse.

Today, you call the superintendent of schools…and an attorney!

The McKinley Funeral Home of Lucasville, Ohio, proudly supports Ohio State Buckeye baseball on Press Pros.

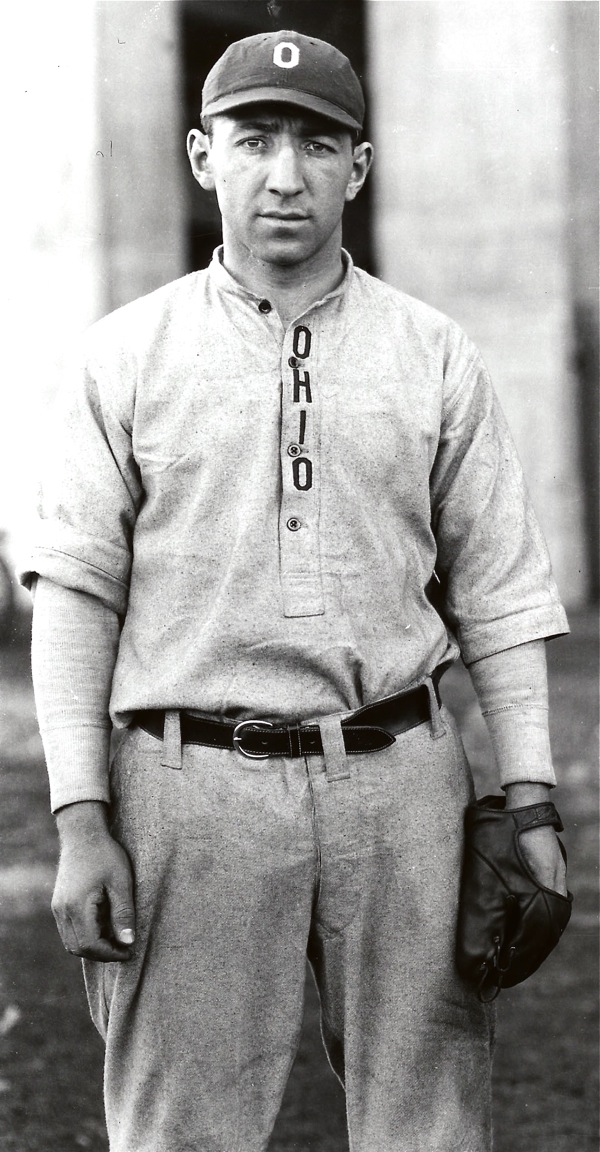

This photo of Ohio State coach Marty Karow, from 1926, tells you everything you need to know about his competitive personality. Hard-core, he was also an All-American fullback in football, and later played for a month in 1927 with the Boston Red Sox. (Ohio State Photo Archives)