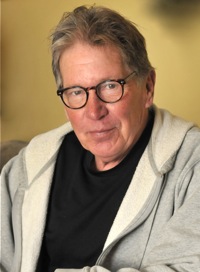

Known for his days as a beat writer for the Cincinnati Reds, his ability to spin a good yarn transcends baseball and sets columnist Greg Hoard apart from most baseball writers. Here’s one of his best…with season’s greetings to all.

CINCINNATI — Christmas is comfortable now. The kids are grown and healthy, and after 35 years of marriage my wife and I are still on speaking terms—most days.

But each Christmas I remember the one that left me with the lesson I have held close all these years.

It was back in the 60s and brutally cold, the kind of cold that makes your teeth hurt and your nostrils frost. It seemed like it had snowed forever.

It had snowed so long that sledding, snowball fights and snow forts weren’t fun any more. It was going to be a white Christmas for sure, but burning the tree for firewood was beginning to look like a real possibility.

We’d had stopped wondering if Santa was coming to town and started facing the fact that the oilman couldn’t make it to the house. You grow up faster on a farm. That’s a fact. It’s impossible for your folks to hide the facts of life.

Wood stoves, coal stoves and fireplaces were working overtime. School had been out for days, weeks, and truth be, we would all have traded a little arithmetic and some serious study hall for all the wood we were chopping and toting, and the coal we were humping to the house.

The hardest thing at our place—and everything was tougher because Dad was out on the truck and caught in the storm up north—was keeping the horses fed, watered and up in the barn at night. I remember throwing straw around the stalls, feeling their warmth, how they smelled in the cold and how the breath from their nostrils seemed to cloud the air like fog and land like a mist on my face.

We had three mares, two of our own—both sorrels—and a big chestnut we boarded for some folks in town. They were great horses, but as with all good ones they had minds of their own and what they seemed to hate above all else was confinement.

No matter how large and grassy the pasture, they pushed at the fences. No matter how bad the weather, the barn was never good enough, never what they wanted. I came to believe that horses are explorers by nature; and that given their head, they will lead you to trouble.

Times weren’t great where we lived and the weather was making things tougher. The Christmas season and all that went with it was largely obscured by the difficulties of everyday life. But folks were doing their best and not just for their own.

Neighbors with tractors were going up and down the roads to clear snow, and folks with trucks or good tire chains checked in on neighbors to see if everything was okay.

If no smoke was coming from someone’s chimney, a neighbor would show up, knocking on the door and asking if there was something wrong or something needed.

By the time Christmas Eve rolled around Mom and I were better off than most. The wind was still whistling through the windowsills and the cracks in the old farmhouse, but we had fires going in both stoves and the fireplace, and for yet another night we let the dogs in to sleep on their favorite rug or curled up at the foot of the bed. Dogs don’t forget favors.

Looking back it was almost cozy. The pantry was stocked and so was the fruit cellar. We had a few presents under the tree and by nightfall the horses were up and the chores were all done.

Not long after we had turned out the lights and rooted down deep under the quilts and comforters, the phone rang. The season was about to lose a little more luster.

It was our nearest neighbor Mr. Lewis, not a friendly type in the first place. Lewis, as my dad observed, “was very churchy but not very kind.”

Lewis informed my mother—in no uncertain words—that our horses were loose and running around, up and down his driveway, into his yard spoiling his family’s Christmas Eve. He pretty much ordered her to come get ’em and fast.

I never liked Lewis. I played with his kids and I’m not so sure they liked him much either.

You can guess how Mom and I felt. Here we were getting into the warmest clothes handy, heading into the dark of night to catch three mares that had no intention of being caught. The dogs were excited and up for the hunt. Tails wagged and they sang their excited songs.

We grabbed flashlights, some carrots and apples and began our fruitless venture.

Lewis’ farm and ours was separated by a quarter mile of gravel road and 40 acres of overgrown pine and cedar, and with all the snow that had fallen it formed the perfect playground for our runaway mares.

We trudged along for hours, it seemed, calling and whistling but it was no good. The dogs fell into the snow for a rest. The horses toyed with us. We would get just so close, almost within reach, and they would break into a trot, pine branches swinging back off their withers and swatting us in the face.

When our fingers and toes were numb and the cold made it hard to move our lips, mom sat down in the snow making an odd sound. At first, I couldn’t tell if she was laughing our crying. The dogs ran to her side, licking and nuzzling.

“Ah, son,” she said, “sit down here with us.”

I sat down in the snow with her and the dogs, the flashlight shining up past her face. She was smiling through the tears and snow on her cheeks.

“I’m betting it’s after midnight,” she said. “We’ve been out here a while. Too long. It’s Christmas! We’re going home. To hell with it.”

As we headed out of the thicket, across the pasture and back toward the house, she seemed determined—not about to be broken.

We kept on slogging along, the snow up to our knees in most places, but we didn’t stop and we found ourselves laughing about the whole night.

When we got up to the house, she stopped and looked up at the chimney, smoke curling toward the clouds.

“What about the horses, Mom?” I said. “What are we gonna do? Lewis will be mad.”

She didn’t say anything for a minute, just kinda laughed under her breath.

“Let him be mad,” she said. “He seems to like it that way. Nothing we can do about that.”

Rounder, the big black and tan shepherd chose just then to bay at the moon, and mom laughed out loud, long and hard.

“As for the horses, it’s Christmas. They’ll come home when they’re ready.”

She stopped and looked around at the night, at all that was around us. “I think,” she said, “the horses always come home at Christmas—most times, anyway.”

She stopped and looked around at the night, at all that was around us. “I think,” she said, “the horses always come home at Christmas—most times, anyway.”

We went in the house. She warmed up coffee and made me one, mostly milk and sugar. The clock chimed once.

The next morning the three mares were gathered down around the barn gate, eager to get back in their stalls. We took the dogs, fed the horses and made sure all the gates were locked down tight.

That Christmas I got a new ball glove, a Wilson, a really good one. It lasted a long time, but not as long as the memory of that Christmas long ago.

Mom was right. On Christmas, the horses come home—most times, anyway.