His ability to hit a baseball, run like a deer, and catch anything that flew were just the baseball attributes of former Red, Vada Pinson. Later in life I was to find out that there was much, much more. He was one of the good guys, too.

CINCINNATI — Just a few days ago I was cleaning out a dresser drawer when I found a small box pushed down in a corner partially buried by ancient underwear and socks that had gone solo.

CINCINNATI — Just a few days ago I was cleaning out a dresser drawer when I found a small box pushed down in a corner partially buried by ancient underwear and socks that had gone solo.

The box puzzled me. What was in it?

Money? Couldn’t be. Money doesn’t last in my house.

Jewelry? Impossible. Never been a rings-and-things guy, not even in the days of Miami Vice and Studio 54.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

What was it? It made a shuffling sound when I shook it back and forth.

What was it? It made a shuffling sound when I shook it back and forth.

I opened the box and—and hey—inside, were 30 or 40 baseball cards, all from the 1950s.

Years ago, in a moment of sheer lunacy, I sold my collection. Got a nice price, too, nearly five grand. But, to be honest, there had not been a time since I let them go that I didn’t regret it. When I walked away from the dealer’s counter with that check in my hand, I left behind an important part of my childhood—in fact, one of the very best parts.

But here was a welcome remnant of that treasure. Most of the cards were from 1959—the player pictured in a circle—and they had that baseball card smell, that distinct, unmistakable scent of history.

As I thumbed through the cards, I wondered why I had kept this particular group, and how they had been separated from the rest. For the most part, they were, marginal players: Bobby Del Greco, Don Hoak, Jungle Jim Rivera, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, Johnny Logan, Billy Goodman and—who would have thought?—Elmer Valo and Granny Hamner.

Some made more sense. There was Rocky Colavito, the dark slugger who played with the Indians and Tigers, and hall of famers Warren Spahn and Whitey Ford. I looked at Ford’s card wondering how many people were still around who actually knew his given name; not many, I figured.

A dull day had suddenly taken a nice turn, and it was about to become much better. Near the bottom of the box, among the last two or three cards, I came to one that held special meaning.

“Look at this,” I said, taking a seat on the side of the bed. “I can’t believe it.”

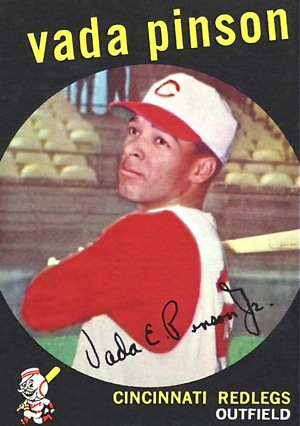

I grew up in the heyday of baseball cards, and none was finer than the 1959 Topps set with Vada Pinson.

It was like answering an unexpected knock at the door and seeing a dear, long absent friend, the one who knows more about you than you know about yourself.

I held the card at the corner, staring at it as if I’d just drawn to an inside straight. It was Vada Pinson, a 1959 Topps; Vada Pinson, the graceful, left-handed hitting center fielder, who years ago captured my respect and admiration.

Pinson played for the Reds from 1958 through ’68, the better part of an 18-year career; 11 formative years in my life—second grade to senior year—years consumed by an abiding love for the game and every thing about it.

Pinson was one helluva’ ballplayer, one of my absolute favorites. In his prime, he was a .300-hitter generally good for 200 hits and 20 homers, and he was blazing fast: 3.3 seconds home-to-first.

But Pinson could not be defined by baseball’s numerical measuring stick. Vada Pinson was a presence. He looked as though his uniform had been tailored for him, as if he’d never broken a sweat or faced a challenge he couldn’t meet. He played hard, but seemingly without effort. When he emerged from the dugout at Crosley Field, it was impossible to take your eyes off the guy.

Pinson had style and good looks, and a nature to match. Win or lose, he could muster a smile and a kind word. After games he would linger in the players’ parking lot outside Crosley Field. He signed every scorecard pushed his way, and he did something very few players did. He actually talked to kids, really talked to them.

To a farm boy from Indiana, they didn’t come much better than Vada Pinson. Sure, he was a good ballplayer—horribly underrated. But he was something else, too. He was a good guy, and, by 14, I had learned that lots of heroes were not necessarily good guys.

That was a truth that continued to be revealed as the years passed and my career took me deeper into baseball. There were good guys and bad guys and sometimes, you found out, unfortunately, there were some whose only redeeming quality was the ability to hit the breaking ball real hard or real far.

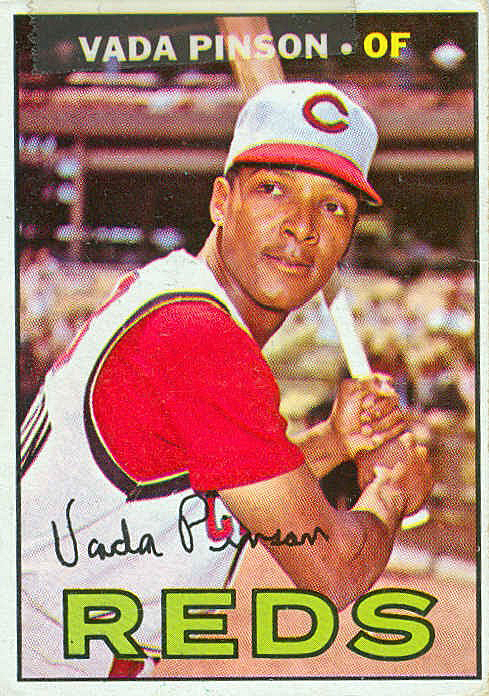

Others consider this the best Pinson baseball card of his 18 major league season – 1967 Topps autographed design.

Vada Pinson was the exception. In 1986 or so, Detroit was in town for the annual Kid Glove Game to benefit Knothole Baseball. I was hanging out around the batting cage, when Hall of Fame writer Earl Lawson pulled me aside.

“There’s somebody I want you to meet,” Earl said. “I remember you told me he was one of your heroes as a kid. Come on.”

The Tigers were taking batting practice, and as we walked toward the cage a man turned and smiled. I knew the face. I knew the smile. “Earl,” he said, “how are you? It’s been a long time.”

It was Vada Pinson, then a coach with Detroit. Still, it looked as though his uniform had been made just for him. Still, he had that presence that set him apart. He didn’t appear to have aged. It seemed as if he would never age.

Long ago, Lawson and Pinson had quarreled over Pinson’s penchant for swinging for the fences, rather than bunting for base hits and taking advantage of his speed. An ongoing difference of opinions on the subject finally led to a whale of a clubhouse fight, but any sign of lingering animosity had passed with the years.

Earl introduced us, told Pinson that I was the new beat writer for The Cincinnati Enquirer and that he had “taught me the ropes, brought me up right” during my days with him at The Cincinnati Post.

Pinson extended his hand and said, “Well, Greg, you are in real trouble.”

We talked for a while before the conversation moved to the visitor’s dugout. He talked about playing at Crosley, his days with the Reds, how it wasn’t the same for him after Frank Robinson was traded to Baltimore.

“That hurt,” he said, “in a lot of ways.”

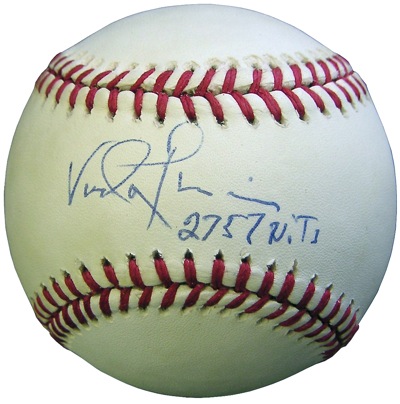

A rare signed baseball by Vada Pinson, on which he inscribed his career hit total – 2757 hits!

I was 34 years old, but I might as well have been sitting on Santa’s lap. Finally, I mustered the courage to ask the question I had always wanted to ask him.

“Vada, do you think you ever got the recognition you deserved? I mean you played center field when the world knew two center fielders.”

He dropped his eyes for a moment, and offered that smile once again. “Willie and Mickey,” he said. He laughed, and looked out on the field, where the grounds crew was making final preparations for the game.

“That’s just the way it was,” he said. “In the National League, there was Willie and the rest of us. In the other league, it was Mickey (Mantle) and everybody else – until his legs started giving out on him.

“There were a lot of good players then, guys I guess you could say didn’t get there due in that same situation: Henry Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Robbie (Frank Robinson).

“See, Willie and Mickey, they were the game. We—and don’t get me wrong I’m not saying I was there with Robbie, Clemente and Aaron, hell no—the rest of us, we were the other guys. That’s just the way it was.”

Game time was growing near and it was time we went our separate ways. I thanked him for his time. “My pleasure,” he said. “I enjoyed it.”

As we stood and shook hands, I said: “I know this. I saw it every time you took the field. You loved the game.”

He nodded; didn’t say anything for a moment. “Yeah,” he finally said, “but there was something I loved more, something I’ve always wondered about.

“I loved to play the trumpet. I took the trumpet with me on the road. Use to practice in my room at the hotel or off in the stairwells, some corner at the ballpark. Always dreamed of being on stage playing my horn.”

I didn’t know what to say. Apparently the surprise showed on my face.

“It’s true,” he said. “But, things happen for a reason I guess.”

I sat there on the side of the bed, studying the card, remembering that time with Vada at Riverfront. The card, like that day, was one of the many unexpected gifts in my life.

I went to the kitchen to find a plastic sandwich bag, something to protect the card. I was thinking about the card, reminiscing, when I caught a glimpse of the calendar on the refrigerator. Christmas was just days away.

Pinson was right. Things happen for a reason.