A mere six years after he was prematurely ushered out as a player, Tony Perez returned as the manager of the Reds for the start of the ’93 season. A mere six weeks into the job, after 44 games, he was fired! It was the third time the organization had tossed him to the curb. But, once again, he stood tall and bigger–in every respect–than those who controlled his fate.

Over the years—still today—people ask me what player I liked best of all those I met as a Reds beat writer and later as a television reporter in Cincinnati. It’s a hard question to answer because there are so many I liked, that I considered a friend and for so many reasons. There was no one funnier than Dave Parker, no one nicer than Davey Concepcion, few as smart and foresighted as John Bench, and no one more kind than Tom Hume.

That said, there was no one I respected and admired more—as a man, as a good human being—than Tony Perez. In a short period of time, I learned why trading Tony sank The Big Red Machine. Tony is one of those people who simply makes all those around him better, and in all respects. No one who knows him would argue that point, and yet, the Reds organization stepped on him and hurt him time and again.

The measure of the man, of course, was that when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2000, there was no question that he would enter as a member of the Reds.

Hopefully, the story that follows begins to explain my admiration for Atanasio. He is simply better than most. – Greg Hoard (June, 2020)

CINCINNATI — After Tony Perez was ushered into retirement late in the 1986 season, wheeled to the curb like last week’s refuse, he held true to character. He remained the good soldier.

CINCINNATI — After Tony Perez was ushered into retirement late in the 1986 season, wheeled to the curb like last week’s refuse, he held true to character. He remained the good soldier.

In the final week of his playing career, he was named the National League Player of The Week. Perez was 8-for-19 at the plate with a home run, three doubles and six RBI.

In the meantime, as the season wound down, the questions continued for Perez. Did he want to coach? Did he want to scout? Did he want to remain with the Reds organization? He never lost patience. He fielded every question; answered as best as he could. He told reporters he thought he would like to coach. It was a response that brought eager responses from his younger teammates, players like Eric Davis, Barry Larkin, Kal Daniels and Paul O’Neill.

“Doggie,” Davis said, “has so much to offer. It would be foolish not to have him on the coaching staff.”

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Post.

Veterans echoed the cause. “Hell, yeah,” said Dave Parker, two-time batting champion and National League MVP. “Who wouldn’t want a man like that around the clubhouse? He’s forgotten more about baseball than most people know.”

“Really, you don’t have to ask,” said Gold Glove third baseman Buddy Bell. “That’s Tony Perez. The man has a wealth of knowledge and this is a young team. We can all benefit from the things he knows.”

But against all this, Pete Rose, manager of the team, raised questions about Perez’s future as a coach. “He’s not coaching material,” said Rose. “But let me explain that. Doggie doesn’t like to come to the park every day at 2 o’clock like coaches have to. That’s not his make-up. Scouting, yes. Doggie would be a great scout. Being the manager, I would like to have him around all the time. But,” Rose continued with a shrug, “it didn’t look like that was in the cards.”

It was not one of Rose’s better moments.

Outside the Reds organization, others in baseball began to take note of what was has happening with Perez. A respected agent was adamant about what was occurring. “It’s imminently clear,” he said, a sharp edge in his voice, “that someone there wants no one around who can detract from the luster of his position. Mark my words.”

As it turned out, Perez was hired as a coach. Some believed that was largely because of owner Marge Schott’s loyalty and appreciation. Schott, for all her flaws, clung to every remnant of the Reds’ glory days, and Perez had always treated Schott with respect and dignity. That, of course, was just his way. He was as much a gentleman as he was a clutch hitter.

Perez became a fixture on the coaching staff. He was there when Rose charged into umpire Dave Pallone, leading to a 30-day suspension. In fact, it was Perez who restrained Rose, keeping him from doing himself further damage. He was there through Rose’s banishment from the game and a season that was trashed due to a controversy that not only ended Rose’s career, but strangled a ballclub.

He survived the departure of general manager Bill Bergesch and his replacement Murray Cook. Next came Bob Quinn, who, along with Schott, hired Lou Piniella as manager, and the man who led the Reds to their wire-to-wire World Championship in 1990.

He survived the departure of general manager Bill Bergesch and his replacement Murray Cook. Next came Bob Quinn, who, along with Schott, hired Lou Piniella as manager, and the man who led the Reds to their wire-to-wire World Championship in 1990.

Perez was there through it all, always there to help, always there to lean on. But the organization was beginning to deteriorate from the top down. Schott had stripped the farm system and her behavior, particularly since the Rose suspension, had become an area of concern for baseball. The commissioner’s eye was always on Schott, and in the dawning day of political correctness, the Reds owner was an easy target. In conversation, she openly said things often heard around the garage in the 1950s. Her remarks slighted Jews, Asians, and African-Americans. On one occasion, she dropped the “n” word in reference to her million dollar outfielders, Dave Parker and Eric Davis.

“That hurt,” Parker said, years later. “That hurt a lot. But we made up. When I was coaching for the Cardinals, I was standing around the batting cage and I felt this little arm on my back. I turned around and it was Marge. I said, ‘Hi, Marge. How you doin’?’ She said, ‘Hi, honey.’ I just smiled. How could you stay mad at a little old lady who had no idea how hurtful her words were?”

In the midst of Schott’s troubles, Piniella announced that he would not return to the Reds as manager. It was 1992 and, by that time, Jim Bowden had succeeded Quinn as GM and was the youngest man to hold that position in the history of the game. That fall, Bowden signed Perez as manager.

Given Schott’s remarks regarding minorities and the societal climate, the choice of Perez was both predictable and transparent, especially since Bowden had also hired Davey Johnson, Bobby Valentine and Ray Knight as either advisors or coaches. Members of the media casually referred to that group as “managers in waiting,” a viewpoint that was encouraged by the fact that Perez was signed to a one-year contract and had little or no input regarding the formulation of the roster.

While all around him seemed to recognize that Perez was a manager of convenience, that he was set-up to fail, “Doggie” went about his business with dignity and an innocence that bordered on naievete. He said he was proud to have the job; honored, and that he would do everything he could to meet the challenge. He made no reference to the wolves at the gate.

His tenure lasted 44 games. After a 1-and-6 road-trip to the west coast, Perez was awakened by an early morning phone call from Bowden. The call came around 7 a.m. The message was simple: “You’re fired.”

The previous night, Bowden had called Johnson asking him to take the position. The next morning, after calling Perez, Bowden called a local sportscaster, cursing him out and banning him from Riverfront Stadium because of a report that Perez would be fired that included a derogatory comments about the methods and means employed by the Reds imperious GM.

Bowden was irate, not because of the report but because the reporter had quoted ESPN’s Peter Gammons saying, “The Reds and their $50,000-a-year general manager, Jim Bowden, have decided to fire Tony Perez as manager after just 44 games, which is preposterous.”

“Let me tell you something,” Bowden roared into the phone, speaking to the broadcaster, “I make a helluva lot more than $50,000, and I make a helluva lot more than you.”

It was the beginning of an insane day. The Reds seemed bound for mindlessness. Clarity of thought was not at a premium.

Reporters spent most of the day tracking down Perez. The good soldier had been “fragged” again. He finally agreed to an interview request in mid-afternoon. I met him in the lobby of his apartment building, One Lytle Place, just yards from the stadium.

He managed a smile as he walked into the lobby, but there was pain and disappointment in his eyes. He slipped into a chair and leaned back with a sigh. “Some kind of day, right?” he said, offering a hollow laugh.”I hear you been banned.”

“I’m in good company,” the sportscaster said. They were quiet for a moment. Then, the interview began.

“You have to be disappointed. You’ve got to be mad, right?”

He said nothing for a moment, just leaned forward and clasped his hands. On one hand he wore a Reds World Series ring. After a long, long moment, he spoke, and ever-so quietly. “You could say that, yes…Forty-four games into the season, I don’t think it’s fair. But it’s happened. It’s a raw deal, but what are you going to do? I’m disappointed. I’ve never been more disappointed in my life.”

He said nothing for a moment, just leaned forward and clasped his hands. On one hand he wore a Reds World Series ring. After a long, long moment, he spoke, and ever-so quietly. “You could say that, yes…Forty-four games into the season, I don’t think it’s fair. But it’s happened. It’s a raw deal, but what are you going to do? I’m disappointed. I’ve never been more disappointed in my life.”

I knew his heart was broken. I wanted him to lash out, as I wanted to lash out. I was angry. I felt he had been used. I urged him on. “C’mon, Doggie,” I said. “Tell me how you feel. This is not the first time this organization has hosed you.”

He looked at me with an odd expression, as if he did not quite understand. “Look,” I said, “you’re the first guy they trade when they are dismantling ‘The Machine.’ Then, they hurry you into retirement; didn’t give you the dignity of making your own call, and now this. They used you. Now, they spit you out.”

He sat there, saying nothing, looking down once in awhile at the championship ring on his finger, as if he was thinking over what he had just heard and what he had lived most of his life.

“Yeah,” he said, finally. “But if it wasn’t for the Reds, I would have nothing. Understand?”

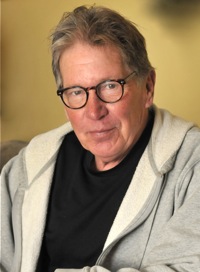

One of the most popular Reds of all time...and a favorite of the fans...Perez was fired after just 44 games as manager. (Press Pros Files)