He’s best known for his relationship with the Brooklyn Dodgers and for helping teammate Jackie Robinson ease the tension of crossing baseball’s color line in 1947. But those who knew or met Pee Wee Reese remember him now for being not only a great ballplayer, but just a good human being.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

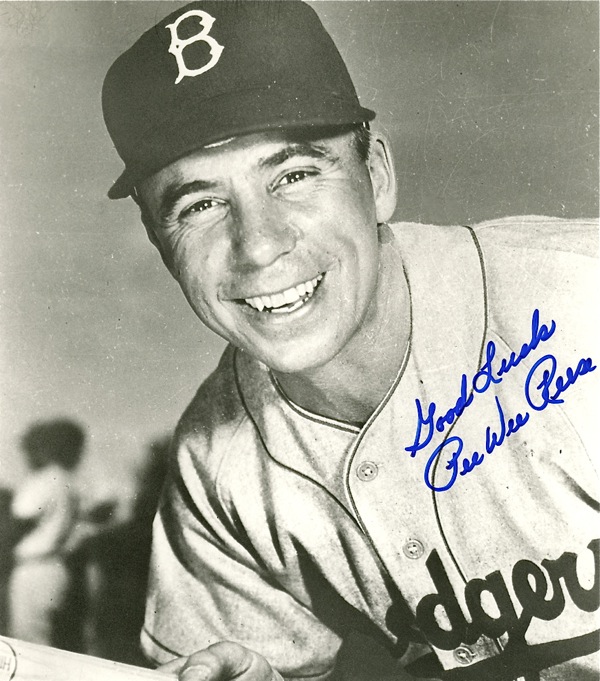

CINCINNATI — He was a man who entered a room and everyone noticed him. He wasn’t tall. He wasn’t striking in appearance. He was quiet and graceful.

His handshake was soft but firm, and when he smiled there were lines in his face, tanned from the golf course, that spoke of long seasons and lessons learned. He smoked a pipe and he laughed easily. He was an Old Spice man, figuratively and literally.

This was Harold Henry “Pee Wee” Reese.

The first time I saw him he was walking through the Reds clubhouse at Riverfront Stadium talking with Johnny Bench and Joe Morgan, joking with Reds broadcaster and former pitcher Joe Nuxhall, who, years ago, had faced him and his Brooklyn Dodger teammates.

“Hard man to get out,” Nuxhall said. “One of those pesky little sh***’s who always managed to get the bat on the ball, but one hell of a guy. I always admired him.”

So, it seemed, did everyone.

By that time, Pee Wee’s career was long over. He came out of Ekron, Kentucky, a tiny town in Meade County, and spent 16 seasons with the Dodgers, from 1940 through 1958. He was Brooklyn’s team captain through the Dodgers’ greatest years, and helped Jackie Robinson, the first black man in major league baseball, make his way. He did so with public displays of acceptance, friendship and respect.

One of the most historic came at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, when spectators booed and jeered, casting racial epithets at Robinson. Reese, a southerner, walked across the field and embraced Robinson.

One of the most historic came at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, when spectators booed and jeered, casting racial epithets at Robinson. Reese, a southerner, walked across the field and embraced Robinson.

Reese earned the Hall of Fame for his performance on the field and for his character during baseball’s most volatile time. He was called “The Little Colonel”.

During the 1980s, Reese worked for Louisville Slugger, and from time to time, he would show up at Riverfront to make sure orders were in place and players were satisfied. He made his rounds in the Reds clubhouse and then would make a run through the visitor’s clubhouse.

After his business was done, he would make his way upstairs to the pressroom and dining room. He would take a seat by the big glass windows looking down on the field, order a Coke with lots of ice, a bag of salted-in-the-shell peanuts and sit down to watch the game.

One night, I mustered up the stuff to go introduce myself. I walked up to his table, told him my name and said, “Mr. Reese, your were one of my father’s favorite players. I just wanted to say hello.”

“Is that right?” he said. “Who were the others?”

I mentioned Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio.

“Good company,” he said, smiling. “Have a seat, son. Have some peanuts. I dearly love these peanuts.”

That first night we talked about the Reds, their fall and their struggle. “Hard to see them in this state,” he said, “after all those great years in the 1970s, but baseball is highs and lows, believe me.”

That first night we talked about the Reds, their fall and their struggle. “Hard to see them in this state,” he said, “after all those great years in the 1970s, but baseball is highs and lows, believe me.”

As time passed, I never missed a chance to visit with Pee Wee. Always it was the same, Pee Wee sipping on a Coke, munching peanuts and occasionally lighting and tamping his pipe, always looking the same, sounding the same, never changing.

One night, I asked him about the 1951 season, when Brooklyn lost a 13 1/2 –game lead to the New York Giants, and faced the Giants in a three-game playoff series. I asked him what it was like when Bobby Thomson hit the three-run homer to win the playoff and knock the Dodgers out of the World Series.

He sat back in his chair, re-lit his pipe and said nothing for a moment. “How many times,” he said, “do you think I have re-lived that moment? How many times do you think I have told that story?”

“Countless times,” I said.

“Countless times, you’re right. But it’s always worth re-telling because something important is lost to so many.”

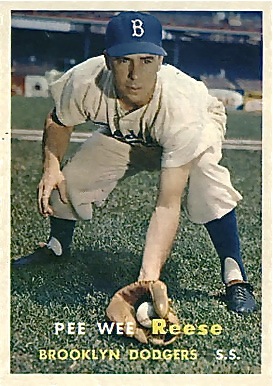

Pee Wee Reese as he appeared on the classic 1957 Topps trading card.

He talked about the first two games of the playoff, the Giants winning the first game, 4-1, and Clem Labine throwing a shutout in the second game. “So,” he said, “deciding game back at the Polo Grounds, October, 3rd, 1951. We got a 4-1 lead going to the ninth. (Don) Newcombe is getting tired.”

He sat there for a moment, enjoying his pipe. It was as if he could see it all playing out before him, all over again. Alvin Dark singled and then Don Mueller followed with a base hit. One out later, Whitey Lockman doubled to left-center; Dark scores, 4-2, two men on.

“So, they call to the bullpen, and as I understand it, Labine was spent and Erskine was putting his curveball in the dirt,” he said. “So, it’s (Ralph) Branca, who pitched the first game. Second pitch, (Bobby) Thomson hits the home run. ‘Shot Heard Round the World.’ We lose. History. Baseball history.”

With that, Reese tapped the bowl of his pipe in an ashtray. “Makes me want a drink,” he said. “But I have to drive back to Louisville, but there is more, son, and this is what I will always remember about that day.

“At the Polo Grounds, you had to walk out to center field to get to the visitor’s clubhouse. The Giant fans are going nuts. It was one of the longest walks I’ve ever made. So, I’m going up the stairs and there is Branca, laying on the steps, face down, crying his heart out.

“That’s what I will always remember most about that day, him thinking the whole season was his loss. Hell, it was our loss, and the saddest part of it is, Ralph never got away from it, never got over it. It scarred him. Wasn’t right. It was one pitch.”

He stood and shook my hand. “I don’t mind telling the story,” Pee Wee said. “I just want people to tell it right, all of it. Just do me a favor. Every chance you get, tell it right.”

Pee Wee Reese played shortstop for the Dodgers from 1940-42, and from 1945-58, the only major leaguer to have reached base three times in one inning, in May of 1951. He later enjoyed a popular broadcasting career with fellow hall-of-famer Dizzy Dean on the NBC "Game Of The Week".