Caught as we all are in the snare of Covid19, I find myself thinking about the things that matter most – memories from baseball. Earl Lawson, the Hall of Fame baseball writer, and John McNamara, the former manager of the Reds, offered me their friendship and guidance in the early days of what turned out to be a long trail.

He sat back and tapped one of those brown, skinny cigarettes from his pack, all the while looking at me with half a smile and, like always, a little laugh there on the edge of his voice.

He sat back and tapped one of those brown, skinny cigarettes from his pack, all the while looking at me with half a smile and, like always, a little laugh there on the edge of his voice.

“Well,” he said, firing his lighter, “you think you got it? Any questions,” he said, wincing, weathering his own smoke. “Anything you can think of?”

He didn’t wait for my answer. Instead, he flagged down the waitress who was on her way to the old, wooden bar that stretched from one tired end of the House of Morgan tavern to the other. It was an old joint, right across the street from our offices at Eighth and Broadway. “Hon,” he said, holding up his glass, “another one of these, please.”

“You got it, Earl,” she said.

Everyone knew Earl Lawson, especially those that followed the Cincinnati Reds or had an abiding interest in baseball. Without exaggeration, Earl was a living legend. He was welcomed and respected all around and I was lucky enough to be his understudy – his protégée, as he liked to say.

Earl had been the Reds beat writer since 1949, first with the Cincinnati Times-Star and for the Cincinnati Post since 1958. His writing was tight. His clothes were sharp. He was fair and feisty with an edge rooted in a tour as an infantryman in the Pacific Theater during World War II. He’d soldiered at Corregidor and Bataan. He was a proud man with a big heart and a deep regard for a job he refused to view as work.

“You’re joking, right?” he’d say. “My office is a ballpark. My hands never get dirty. I stay in the finest hotels in the country, eat at the best restaurants and I seldom, if ever, spend my own money.”

Earl Lawson: “My office is a ballpark. I stay in the finest hotels in the country, and I seldom, if ever, spend my own money.”

Earl loved the job so much he and almost never took a day off. But lately his back had been nagging him. Beyond that, his doctors had increased his heart medicine and—perhaps most significant—after years as a divorcee, Earl had fallen in love again, deeply and hopelessly in love.

So, after more than a year working at his side, he was sending me off on my first road trip with the Reds.

“You’re gonna do fine,” he said, sipping at his drink. “You been at this a while, now. Hell, we wouldn’t send ya if we didn’t think you were up to it.”

I nodded, trying to act like the responsibility didn’t make me nervous, but the more Earl offered encouragement the more I wanted a Scotch myself, maybe more than one.

“Here’s the thing,” he said, finally, “just stick to the facts and you can’t go wrong. Follow your own style, but play it pretty straight. What’s that term you use?”

“Show dog,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said, laughing. “Don’t try to be a show dog on your first trip, right out of the chute, and if you get confused or got a question, don’t be afraid to ask somebody. You got friends in that clubhouse. You can’t do this job without friends, God knows.

“In this job you are only as good as the people who will talk to you, the people who trust you. Without them, you are nothin’, nothin’.”

With that, Earl finished his drink and tossed enough cash on the table to cover the bill and a generous tip.

My preparation was complete, or so I thought. We were standing on the street preparing to go our separate ways when he suddenly stopped. He was 15, maybe 20 feet away but I could still pick-up Earl’s predilection for fine and fancy cologne. The joke around the office was tried and true: “You know when Earl’s in the building before he ever gets off the elevator. You can smell him and he sure smells sweet.”

He stood there smiling at me, his hands in his pockets. “Do a good job,” he said. “I’ll be watching.”

Great, I thought, nothing like a little added pressure. I walked to my car wishing I’d had a Scotch or two, or three, or…

It was September 1981, a strike season. My assignment was a four-game series in Philadelphia, a series that mattered. The Reds were trying to win the Western Division and land a spot in the expanded playoffs, but time was running out.

THE DAY BEFORE we left, September 2, Tom Seaver threw eight innings of two-hit shutout ball. Joe Price added a scoreless ninth and the Reds coasted to a 7-0 win over Montreal. For all its comfort, the win still left the Reds three games behind Houston, which was showing no signs of loosening its hold on first place in the West.

The first day in Philly went well for the Reds. A rookie on the beat couldn’t have asked for much more. The Reds won, 9-3, and the game was never really in question. Afterward, the mood in the clubhouse was light and the music was loud.

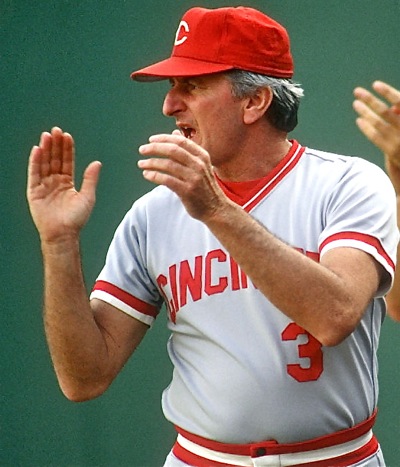

“Sad to report,” McNamara said to Earl Lawson following my first road trip with the Reds. “He did fine. He listens.”

I made my rounds for a word with the principals in the game—mostly George Foster, who had driven in five runs four on a grand slam in the eighth—and was on my way to Manager John McNamara’s office when I saw Dave Collins talking with a several other players. He was animated, intense. His mood didn’t seem to match the overall atmosphere. I could only hear a bit of his conversation. “It’s not right,” he said.

Collins was a hard-nosed player. He left nothing in the dugout. He was a fast, contact hitter; a forthright sort who was generally friendly and upbeat.

I started towards Collins’ locker, but Dave Concepcion caught my eye. He shook his head, suggesting that might not be a good idea.

“Not a good time,” Davey said, after I sidled up to his locker stall. Ray Knight was standing nearby. “Nah, Greg,” Knight said. “He’s got a burr just now. Let it be.”

My curiosity was piqued. Collins was 1-for-3 with a stolen base, a run scored and a walk. I ducked back in to McNamara’s office, where he and coaches Russ Nixon and Bill Fischer were kicked back having a beer.

“You’re back again, Rook,” Mac said. “Earl would have his story written by now. What’s on your mind?”

Collins, I said, seemed upset about something but I wasn’t sure why. Before I could say anything more, Mac stared at his beer, then lifted a hand stopping me in mid-stream.

“Nothing for you to worry about,” he said. “Trust me.”

“He’s right, Bud,” Nixon said. “Don’t give it a thought.”

Nixon had played minor league ball with my uncle and had taken me under his wing early on. I trusted him implicitly; Russ knew more about me than I wanted most to know.

“Okay,” I said. “I just don’t want to get burned.”

Mac laughed. “You won’t,” he said. “You won’t. Believe me.”

“Relax, Bud,” Nixon said. “There’s no fire there and this ain’t brain surgery.”

The next day was good for me, not so good for the Reds. My competition had no screaming headlines about Dave Collins—to my relief—and that night the Reds lost, 7-6. After the game, I made a conscious effort to check on Collins. He was no different than anyone else: quiet after the loss, dressing quickly with little to say.

The next two nights—a loss Saturday, a win Sunday, both games decided by a single run—Collins was visibly upset. Saturday night he was miffed. Sunday he was tilting toward anger: tossing his gear around his locker, talking to those who would listen.

Nostalgic image…Frank Robinson cranks a home run at old Crosley Field…with the left field terrace and the 328 sign in the background.

When I approached him, he was, as usual, both articulate and astute. He was angry, he said, because he was being needlessly replaced late in games for defensive purposes. McNamara was pulling him for Sammy Mejias.

“Nothing against Sammy but they don’t need to do this,” he said. “I am not a defensive liability.”

Above everything else, his sincerity led me to take I the story to Mac, whose initial reaction was a long, tired sigh. “We split four in Philly, we’re two back on Houston and he’s talking about coming out late…”

With that, he stopped as if he didn’t want to address what he didn’t comprehend.

“Sit down,” he said, dressing for the bus and the flight home. “Let me lay this out for you, and I’m doin’ this only because you are new to this.”

He referred to Collins as a “hard-nosed, solid” player. He said he enjoyed having him on the team. “I like Dave,” he said. “I like him a lot.”

His weakness, Mac continued, was that he trusted his speed too much and because of that sometimes played a base hit into extra bases. Beyond that, there were issues with his arm. It was, he said, a little short.

For those reasons, he was dropping Mejias in late in close games, like Saturday and Sunday, or in games that were basically decided in the late innings, like Thursday night when the Reds had coasted to a 9-3 win.

“Dave knows this,” Mac said, and there was another of those long sighs. “We’ve talked about it. It’s a matter of pride, and I like it that he gets (ticked)-off. It means something to him. He’s the kinda guy who will keep after it. He’s always pushing himself. But my job is to win games.

“Now,” Mac said, giving me a hard look. He had these blue eyes that could pierce porcelain, eyes that would lock you in place. “You gonna write this? Does it serve any one? Does it serve a purpose?”

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Post.

I didn’t write it. I wrote the game.

When we got home, the Reds were beginning a three-game series with the Padres. Earl was on the field for batting practice talking with McNamara.

“There he is,” Earl said, pounding me on the back. “How did my boy do, Mac, okay? You have to set him straight? I told him to count on his friends.”

Mac smiled at me and held that smile, not saying a word for a long, long moment. Once again, he held me with those eyes.

“Sad to report, Earl,” he said, smiling. “He did fine. He listens.”

“I told him to count on his friends,” Earl offered. “Can’t do this job without friends.”

Mac nodded, turning his attention to the batting cage.

“Any job, Earl,” he said. “Any job. Right, kid?”

Bats for every occasion, including ‘fungos’. Phoenix is proud to support Buckeye baseball on Press Pros.