I watched him as a kid, and waited a lifetime for the opportunity to tell him how much his example had meant to my childhood. But when we at last came fact to face it wasn’t what I thought it would – hoped it would be. I discovered that we all need a change of life.

CINCINNATI—It seems there was never a time when the name didn’t hold a certain significance in my life: Carl Erskine.

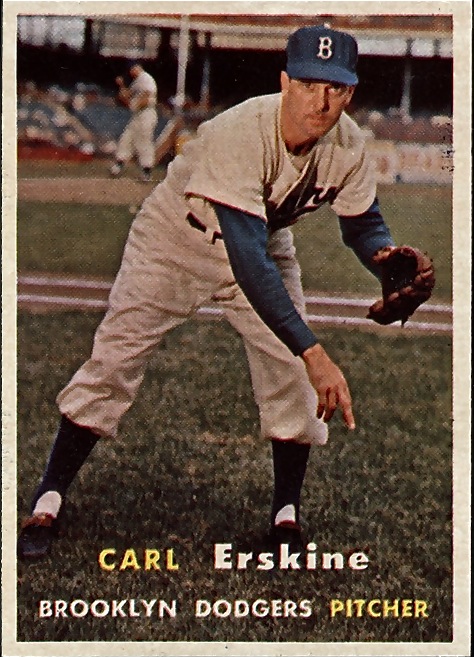

First, there was the 1957 Topps baseball card. There he was wearing that Brooklyn Dodger uniform like it was tailored just for him. The cap was perched perfectly on his head and he peered beneath its brim with a shocking intensity.

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Post.

“That’s a pro,” my dad said. “You can tell by looking at the man.”

Next came the glove, my first one. Dad said it cost $5.95 at Western Auto. Mom said that was too much money to spend on a glove for a boy that was only five years old.

It was a Nokoma and there in the palm, right there in the pocket, was the name: Carl Erskine. None of my buddies had a glove like that.

Lots of times we used gloves for bases back then, but I fudged on that. I didn’t want anybody stepping on it and I wouldn’t let anybody use it, either. It was too important to me. Because of that glove I got into my first shoving matches. Somebody might have even thrown a punch, but I doubt it.

On top of all this, I learned that my dad knew Erskine. Dad had signed a contract with the Dodgers in 1941 or ’42, but shortly after that he went off to fight in World War II. A few years and five major battle stars later he came home, but the Dodgers no longer had any interest in him.

When he talked about it—which was rarely—I could tell it made him sad, but he continued to play ball traveling around the Midwest playing in Industrial and Independent leagues and somewhere along the way he had become acquainted with Erskine, who lived in Anderson, Indiana, and came home in the off-season.

Besides Erskine, Dad had come to know Billy Herman, who he said was one of the best second basemen ever, who lived in New Albany just down the road, and Pee Wee Reese, the famous Pee Wee Reese. We all knew Pee Wee. We all knew he came from Louisville, which was just across the river and the closest place to our little town you could call a city.

In retrospect, I think Dad told us so much about Erskine and Herman and Pee Wee so that we would understand that a boy from any place, anywhere, could realize his dreams, dreams like playing big league ball.

Carl Erskine as he appeared on that favorite 1957 Topps trading card.

But oddly enough and as time went on, I kept crossing paths with Erskine. I ran into him in high school and in college when Hanover played Anderson College, and several times when I was covering the Reds, but there was never an opportunity to do anything other than to say hello.

Then, a few years ago, my friend Jim Plump and I were taking Danny Dean to meet former Red Jim O’Toole at Great American Ball Park. Dean loved O’Toole and had since childhood but had never met him. On our way to the private suites, we ran into Erskine, who was stepping out of an elevator.

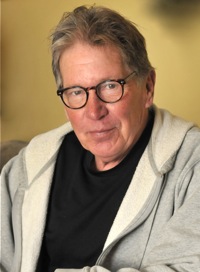

He was dressed in gray slacks and a red sweater. He had the tan of a deep-sea fisherman and moved as if he were 46, not 86.

Plump was first to see him. “Carl Erskine, how are you, sir?” he said.

“Mr. Erskine,” I said, somehow stirred even though I had spent the better part of my life working with professional athletes.

“Hi, fellas,” Erskine said, hurrying on to wherever he was going. He was clearly in a hurry and had no intention of stopping to talk with complete strangers.

I made up my mind that instant that I would run him down for an interview, and in the process, tell him what a roll he had played in my childhood. I was grateful and wanted him to know it.

A few weeks later, I landed a phone number for Erskine in Anderson, and on a sunny afternoon I drudged up the courage to call him.

He answered after a few quick rings and was genuinely pleasant. I identified myself and said I was hoping he had the time to talk about his career.

He said nothing for a moment, a moment long enough that I could feel some of my excitement begin to flag.

“Well,” he said, “I guess we can do that. But right now (he paused again) isn’t a good time.”

He said he was headed to the dentist or something. Honestly, I don’t remember where he had to be. He suggested I call back in a couple of days. I suggested a day or two that would be opportune. He said either would be fine.

I called on the first appointed day and there was no answer. On the next attempt, he picked up.

Yes, sure, he remembered, and he apologized for not being home the previous day. “Just a lot going on,” he said.

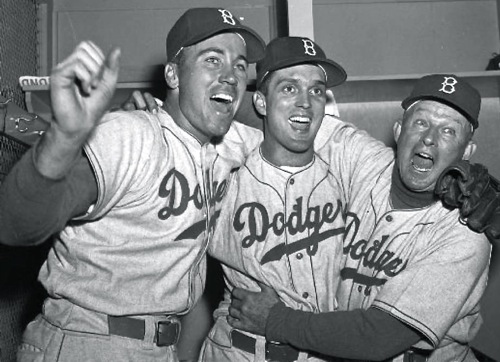

Erkine (center) celebrates the Dodgers winning the 1953 pennant with Duke Snider (left) and manager Chuck Dressen (right).

So, we launched in. I told him that I had made a study of the Brooklyn Dodgers and that I had read everything I could get my hands on, mentioning a couple of titles like The Boys of Summer, by Roger Kahn.

He liked Kahn, he said, then added: ‘Some of it is pretty good. Others took, let’s say, some liberties.”

We discussed different players: Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Carl Furillo, Reese, of course, but I could tell he wasn’t really enthused with the conversation.

Finally, and somewhat discouraged, I asked him what he thought about most when he considered his baseball career.

“Now, it’s like it was a different life,” he said. “I thank the Lord for those years because that allowed me to meet so many people who became very influential in my life.”

“Like who, sir?”

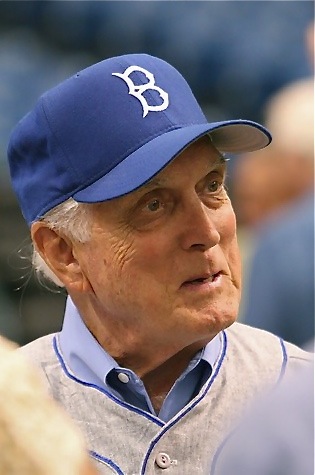

Carl Erskine is still a Dodger legend for his 14 strikeouts in Game 3 of the 1953 World Series.

“Well, like Bishop Fulton J. Sheen,” he said, “and Dale Carenegie. Norman Vincent Peale. They were people who influenced my life so much it is hard for me to describe…

“It was people like that that I would not have had the opportunity to meet had it not been for baseball.”

They helped him, he said, prepare for the second stage of his life.

“I played for 12 years,” he said. “I was just 32 when I left the game. I had a lot of life ahead of me.”

He returned home to Anderson after his career where he devoted his life to the community and those, like his son, Jimmy, who suffer from Down syndrome. He still worked for the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), helping former players who suffer from physical and financial problems. His contributions to his hometown were countless, and in Brooklyn a street was named for him.

I started to tell him about my glove and the baseball card, but decided not to. It didn’t seem like it would be important to him, and truthfully, I didn’t get the idea he was too wild about doing the interview in the first place.

Still, he was kind enough to talk with me and I will long remember that call even though it didn’t go very well, leaving me somewhat deflated.

But, long ago I learned that something good almost always comes from every interview, the good ones, the bad ones and the ones that just go flat. This one did, too.

There are far too many ballplayers who cling to every moment they spent in the game and do so to a their detrimental effect, and there are those like Erskine, who move on and teach us that—no matter what one might do—there is always a next step.

There are far too many ballplayers who cling to every moment they spent in the game and do so to a their detrimental effect, and there are those like Erskine, who move on and teach us that—no matter what one might do—there is always a next step.

When I was a five-year-old boy his baseball card and the glove with his name on it led me to try and be the best ballplayer I could be.

When I was turning 60 or so, he taught me there was probably something else ahead, and if I hadn’t found it just yet, I better keep looking.

Years have passed since then and I still walk around, eyes wide open – most times.