The late Willie Stargell was a man who gained respect in countless ways, one of baseball’s most popular players, and a hall of famer on and off the field. And yet, he was more than that. He was an old soul and a good one.

CINCINNATI—He sat at his locker, a large cup of coffee in his right hand. In his left, he toyed with two new bats, studying them from the knob to the barrel.

CINCINNATI—He sat at his locker, a large cup of coffee in his right hand. In his left, he toyed with two new bats, studying them from the knob to the barrel.

It was three hours before first pitch at Riverfront Stadium, about the time the visiting locker room begins to awaken. The coffee pots were filled and steaming. There were donuts and muffins aplenty for those just crawling out of the sack and hurrying to the ballpark; sandwich meat and soup for others.

The Pirates were in town and after all the playoff games between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, all the sweat spent and heated words exchanged over the years, the waters between the Pirates and the Reds ran a little rough.

It was early in the 1980 season and Willie Stargell, a fixture in Pittsburgh for two decades, wasn’t getting that much playing time. Still, every at-bat, every moment he spent on the field reflected his sense of honor and respect for the game. Pirates manager Chuck Tanner had once said, “Having Willie Stargell on your team is like having a diamond ring on your finger.”

Nothing had come easy for Wilver Dornell Stargell. All he had earned and worked for was cherished. He was of the color and generation of players who had faced trials beyond those presented by the game, itself. Yet, he had survived and flourished, and done so with a smile on his face, not a chip on his shoulder.

His teammates called him “Pops”, an expression of admiration, appreciation and, beyond all else, affection. No one ignored Stargell, and he ignored no one. He looked all in the eye and never down on a soul.

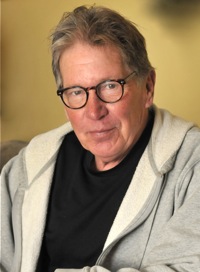

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Some of his teammates were in the training room; some in the players’ lounge reading the papers or watching television. Others were already at work in the batting cages, and some were just making their way through the door, a little worse for wear. There are some—and always have been—who handle the road better than others. For those somewhat tardy, Stargell offered a burr.

“Nice to see ya,” he’d say, maybe smiling, maybe not. For some, he would speak and then glance at the large clock that hung over the door that led to the field, re-enforcing his point.

I had introduced myself and ask him if he could spare a little time.

“You know what,” he said, “the road can eat ya up—if ya’ let it. Sneak up on you and before you know it, it’s got a hold on ya’ and some just can’t shake it.”

He sipped his coffee and studied his bats, but nothing in that clubhouse escaped his eye.

“So,” he said, “what was it you wanted to talk about?” Before I could answer he held his hand out as if he was stopping traffic. “Not the ‘We Are Family’ thing,” he said. “Sister Sledge and all that. That’s old news, man. That’s last year. This, this is a whole new thing—whole new season.”

Okay, I said, let’s talk about you: what’s passed and where you are now.

Can you name these former Pirate greats from the pre-‘Lumber Yard’ years? Find the answers below.

He smiled then, big as you please. His eyes were his most striking feature. They were large, a rich brown and steady as a stone. They came with a weight. You knew he was looking at you and you knew you were being examined. He was a man, it seemed, who looked for worth, one kind or another.

I ask him if he was easing toward retirement. He leaned the bats he had been holding into a corner of his locker, and sighed. “I wonder about that,” he said, “if anybody in this game ‘eases’ toward retirement.

“Lots are re-tired. They don’t have much to say about it. No choice whatsoever. Don’t let the door hit you in the ass, and for some it’s like that famous sayin’, ‘They just fade away.’”

That’s MacArthur, I offered. Talking about old soldiers. The general.

“Yeah,” Stargell said. “The one with the pipe.”

“Yep,” I said. We shared a chuckle.

He was warming to the conversation when Bill Madlock, beginning his second full season with the Pirates and already a two-time batting champ, rolled up to Stargell’s locker.

“Pops,” he said. “You got a minute. Sorry to interrupt. Won’t be long at all.” Madlock wanted to talk about one of the Reds relievers they were apt to face in the series.

I stood apart while they discussed the pitcher’s tendencies in quiet tones. “Sorry,” Stargell said, returning to our interview. “Where were we? Oh, yeah, retiring. Baseball isn’t that much different than any other profession. You reach a point when you just aren’t what you were, and you got to recognize that.

I stood apart while they discussed the pitcher’s tendencies in quiet tones. “Sorry,” Stargell said, returning to our interview. “Where were we? Oh, yeah, retiring. Baseball isn’t that much different than any other profession. You reach a point when you just aren’t what you were, and you got to recognize that.

“You’ve seen it in your job. Guy stays too long and it’s—no other way to put—it’s embarrassing. It happens all over the place.

“Besides,” he said, reaching for his sleeves and his game jersey. He stopped, then, to ask the clubhouse attendant what color jerseys they were wearing that night. “Gold, black, white—what? Good lookin’, but confusing. Hey, what color pants? Man got to ask what pants he’s wearing. Don’t seem right. Damn.

“What was I saying? Oh, yeah, how no one should go out looking bad. Man, I have played with and against some of the very best this game has seen, ever will see.

“I played with the very best. No one like him, ever!” He recognized the question on my face and those heavy eyes rested on me, some disappointment present.

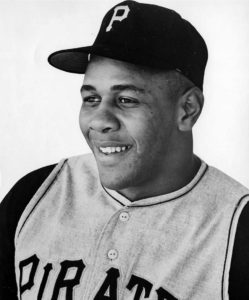

“Clemente,” he said. “Roberto Clemente. None like him in the world, in the world I’m saying: at the plate, in the field, throwing, fielding, running the bases. The man could beat you so many ways. He could beat you by just being in the on-deck circle.

“Here’s what I’m sayin’. You got a man on base Roberto is up. Well, he ain’t gonna get nothin’ to hit. So, Roberto walks and maybe the man on has been able to steal a base because pitches to Roberto been in the dirt—somethin’. Now, here comes the next hitter and the pitcher—no denying this—they relax a little, maybe subconsciously, because Roberto didn’t hurt him. And that guy at the plate gets something he can handle. Base hit. Scores a run, maybe two, the way Roberto could run and force the play. That could mean the game and all Roberto did was go to the plate then run the bases like a blasted, crazy horse. Best ever, in my opinion. The Lord just took him so early (Clemente died at 38 in a plane crash while delivering food and clothing to earthquake victims in Nicaragua).”

Stargell did not want to linger over his own numbers. At that point—he would play a minimal role for the Pirates the next three seasons—he had over 2,000 hits and 1,400 RBI. He had hit over 450 home runs, so many of them other-worldly shots. He had over 900 extra base hits.

“Hall of Fame numbers,” I offered.

“We’ll see,” he said, smiling. “We shall see. Nothing is a given in this game. Point is we all would like to go out on a high note, but the world don’t work that way for everybody.”

He acknowledged that his playing days were coming to an end. “The bones, man. They ache,” he said.

Then, he quickly added that there were other things in the game he wanted to accomplish.”

“Manage?”

“We’ll see,” he said. Again, he smiled.

Our time was running out. The music was turned up: Earth, Wind and Fire charged the clubhouse. All around players were getting jacked up for the game, and our discussion was continually interrupted by one or another of his teammates as first pitch drew closer. Some who visited him were serious. Catcher Ed Ott asked Stargell about pitching to Johnny Bench. They talked quietly.

“Not much works,” Stargell concluded. Ott agreed.

The effervescent Dave Parker stopped by Stargell’s locker. “Pops,” he said, full of himself and his talent, “I think I got three hits in this bat tonight. What d’ya think?”

“Betcha,” Stargell said. “Dinner on me.”

Bowlerstore.com, in Versailles, Ohio, is a proud sponsor of Buckeyes baseball on Press Pros Magazine.com.

Teammates asked about pitchers, situations, the tendencies of umpires. They ask about good restaurants, bars off the beaten path, and—oh, by the way—had he seen that cute little waitress at the hotel. Pretty soon it was time for writers to leave the clubhouse.

“I didn’t give you much, man,” Stargell said, as we parted.

“More than you realize,” I said.

I ended up writing a story about respect and how we might be getting a last look at an aging player still so valuable to his team and the game; a man—above all—so important to his teammates.

On Sunday, getaway day, I stopped in the Pirates clubhouse to thank Stargell for his cooperation. He was standing at his locker with Parker and Tanner.

We talked briefly and shook hands. As I turned to leave, he called me back. “Hey, wait,” he said, pulling something from the back of his locker.

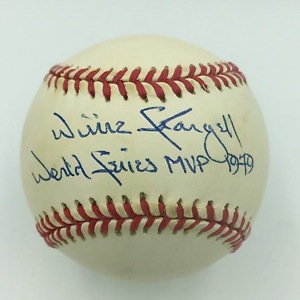

“For you,” he said, sticking a Stargell Star on the lapel of my jacket. “I enjoyed our talk.”

“For you,” he said, sticking a Stargell Star on the lapel of my jacket. “I enjoyed our talk.”

“Better be appreciatin’ the hell outta that,” Parker said. “The man here don’t just be passing them out like candy, ‘specially to sports writers.”

I was as proud as I could be, and I kept that star for years. But some how with time and all that comes with it, the star was lost. I’m shamed that I was so careless. But I never forgot that time with Stargell. He was a man who gained respect in countless ways, and he was more than that. He was an old soul and a good one.

After his death in April 2001, it was Joe Morgan who paid Stargell the most telling tribute.

“When I played,” Morgan said, ‘there were 600 baseball players and 599 of them loved Willie Stargell. He’s the only guy I could have said that about. He never made anybody look bad and he never said anything bad about anybody.” (Former Pirate greats above (l to r): Roberto Clemente, Matty Alou, Willie Stargell, and Manny Mota)

His terrifying swing produced 450 home runs...and a lot more massive line drives that never gained the elevation to leave the park. (Photos Courtesy of the Ewing private collection, Cambridge, Oh)