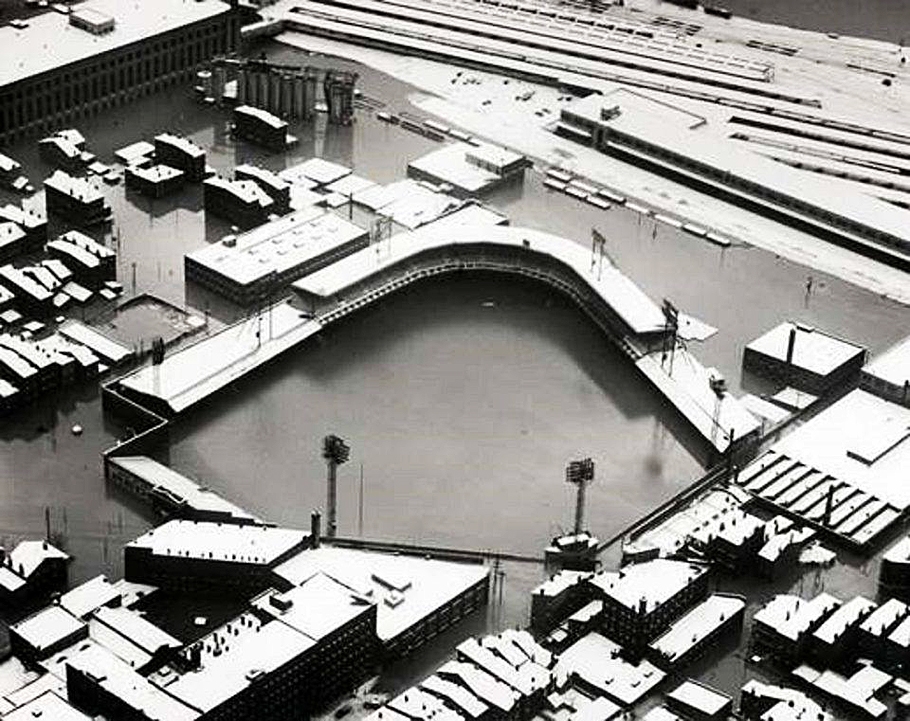

The absurdity of the old Polo Grounds, in New York City, original home of the New York Giants (now San Francisco) and the New York Mets. (Press Pros Files)

The state baseball tournament is played this weekend in Canal Park, one of my favorite venues for such an affair, because the park reminds us of some of the old-time parks that were asymmetrical, different, and a little kooky.

Akron, OH — Once upon a time, in the era of stirrup socks, suicide squeeze bunts, ball park mustard and no softball-style City Connect uniforms, baseball was played in quaint and diverse parks, stadiums and fields.

Akron, OH — Once upon a time, in the era of stirrup socks, suicide squeeze bunts, ball park mustard and no softball-style City Connect uniforms, baseball was played in quaint and diverse parks, stadiums and fields.

There were quirks, nooks and crannies.

The Cincinnati Reds once played in Crosley Field, a hazard for left fielders. Instead of a warning track in front of the wall, there was a 15-degree incline, a slight hill.

Hall of famer Hal McCoy writes UD Flyer basketball and the OHSAA state baseball tournament for Press Pros.

It was not uncommon to see outfielders fall as they chased fly balls up that hill. Former Reds outfielder Alex Johnson once fell three times in one game, twice on his back and once face first into the grass.

When the OHSAA state baseball tournament commences this weekend in Akron, they’ll play in asymmetrical Canal Park, home to the Class AA Akron RubberDucks.

The park is in downtown Akron, on Main Street, near the old Ohio-Erie Canal and it has its danger points for outfielders.

It is 331 feet to the left field corner, 376 to left center, 400 to center, 375 to right center and 337 to right field. But it has a couple of hazards, like left center where the wall tucks in, creating an alcove where triples are born.

Most old parks were built in the downtown areas on oddly-shaped pieces of real estate that forced designers and architects to be creative with their slide rules.

The most oddly-shaped ball park of all time was the Polo Grounds, which sat across the Harlem River from Yankee Stadium up on Coogan’s Bluff.

Its horseshoe shape made it look more like Ohio State’s football stadium than a baseball park. It was only 279 feet to left and 258 feet to right. But it was 483 feet to dead center.

Cleveland Indians fans still despise and abhor the place. In the first game of the 1954 World Series, Cleveland’s Vic Wertz hit the famous 460-foot blast to center that Willie Mays caught with his back to the infield, over the shoulder.

In the same game, New York pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes lofted a 260-foot fly ball to right that crash landed into the seats for a home run.

Said pitcher Early Wynn, “I can stand on the mound and urinate over that right field wall.” And manager Al Lopez said, “We were beat by the longest out of the year and the shortest home run of the year.”

You can’t see the Crosley Field terrace in this photo. The ballpark was this far underwater during the 1937 flood.

Boston’s Fenway Park, built in 1912, still stands and the 37-foot Green Monster still stands in left field, just 310 feet from home plate. Routine fly balls clear the wall and disrupt traffic on the Massachusetts Turnpike. Hard line drives that might be home runs in other parks, clank off the Green Monster and ricochet to the left fielder and he holds the hitter to a single.

And then there is the Pesky Pole in right field, just 302 feet to the right-field corner. It is named after Boston infielder Johnny Pesky, who was adept at curling home runs just inside the pole.

The old Yankee Stadium was another playing field with odd dimensions. It was only 296 feet to right field, built that way to accommodate the towering fly balls hit by Babe Ruth, which earned the stadium the name The House That Ruth Built.

Huffer Chiropractic can help your athlete perform at their best – with offices in Osgood, Jackson Center, and Dublin, Ohio.

But if the Bambino hit one to dead center it was where home runs went to die. It was 500 feet to the center field wall. And there was a flag pole and three marble monuments that were in the field of play.

The monuments were memorials to former manager Miller Huggins, Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Some fans and even some players thought those gentlemen were buried there. Not true, just an urban legend.

Another old park still surviving is Wrigley Field. Not only does if have walls jutting in and out in left center and right center, the walls are brick and the ivy that covers them does not cushion outfielders who run after fly balls. Many outfielders have suffered broken arms, dislocated shoulders and flattened noses running full speed into the unforgiving bricks.

To make it even more challenging, there is a wire basket on top of the walls that protrude in front of the walls. Outfielders who get to the wall, ready to snag fly balls, watch those balls plop into those baskets for a home run.

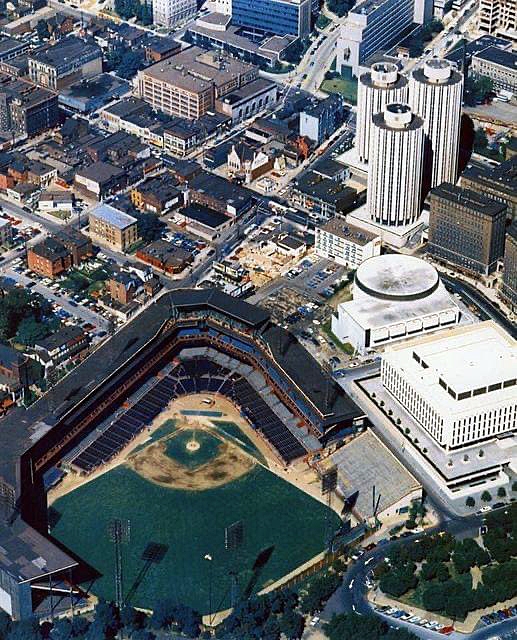

The Pittsburgh Pirates once played in Forbes Field where the fences were so far back that three light tower stanchions were in the field of play.

It was 457 feet to left center, until slugger Hank Greenberg arrived. To accommodate his awesome power, they moved that fence in 40 feet and sports writers dubbed it “Greenberg’s Garden.”

Cleveland Municipal Stadium, called “The Mistake on the Lake,” was a pitcher’s paradise when it opened because the fences could barely be seen by the naked eye from the pitcher’s mound — 470 feet to center and 463 feet down each line.

Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field was literally carved out of a city block in downtown…and was 457 field to dead center. and the batting cage was out there and part of the field.

When maverick Bill Veeck bought the Indians in 1947 he moved all the fences in to make the place respectable, except for those howling winds off Lake Erie.

When Briggs/Tiger Stadium was built, it had no upper deck. So they built one and it was unique. Because Trumbull Avenue was right behind the right field stands, they had to build it so that the upper deck protruded toward the playing field.

It overhung the lower deck and was 10 feet closer to home plate above the right field fence. Outfielders who camped under fly balls 15 feet from the fence thought they had an easy catch until balls dropped into the upper deck.

Detroit’s Norm Cash knew how to cash in and made a habit of lofting upper deck home runs that wouldn’t have been homers into the lower deck.

Before Dodger Stadium was completed, the Los Angeles Dodgers played three seasons in the Los Angeles Coliseum. It was so narrow, a legitimate baseball configuration was impossible.

The left field fence was only 250 feet from home plate, close to the dimensions of a Little League Park. They constructed a high screen atop the wall, but that didn’t stop Wally Moon. He became adept at hitting towering fly balls to left that cleared the screen and writers called them Moon Shots.

There won’t be any light stanchions, monuments, flag poles, grassy inclines or monsters of any color for the state tournament, but there are enough ball park idiosyncrasies to make the weekend interesting for the high school boys.

Sad picture of history…Forbes Field as it was left for the new Three Rivers Stadium in 1971.