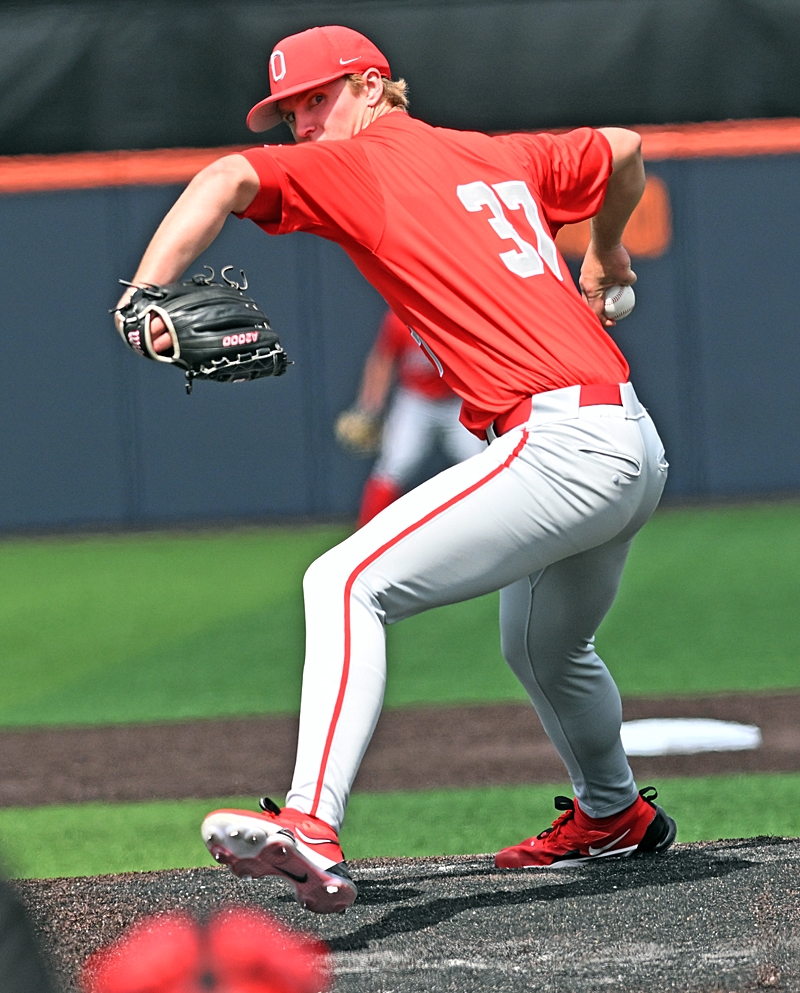

Ohio State’s Zach Brown is a freshman from Santa Ana, California, and learning the craft of pitching at the next level. (Press Pros Feature Photos)

The pitching coach of the Ohio State Buckeyes shares in insights on one of the most important rudiments of baseball, and baseball at every level – why to some throwing strikes comes easy, and not for others…pitching and velocity…and how to put a good or bad performance behind you and move on.

It’s the bane of every baseball coach in America.

It’s the bane of every baseball coach in America.

Baseball, you see, is about 80% dictated by your ability to pitch. If you don’t believe that, just try to win at any level without good pitching. And when Yankees catcher Yogi Berra once said, “Good pitching will beat good hitting every time, and vice-versa”, what he meant was just that. If you can’t pitch you’re going to get your brains beat out in baseball.

High School pitchers need to remember…that pitchers at the next level were in your shoes as recently as one year ago.

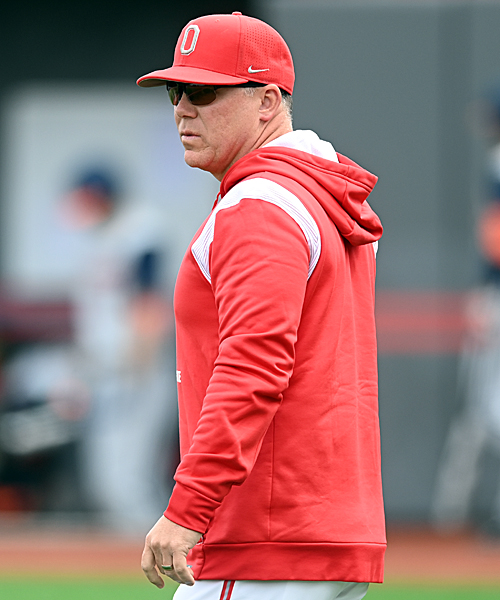

So with that in mind we recently cornered Ohio State assistant head coach, and pitching coach Sean Allen to share his insights on pitching – ideas and concepts on throwing strikes, throwing too many strikes, and how to put a bad performance behind you. And if you’re a high school baseball coach trying to develop y0ung pitchers, you could do so much worse than consider what Allen has to say.

He came to Ohio State with Bill Mosiello in 2022 after spending six seasons as the pitching coach at the University of Texas for head coach David Pierce. Where, in 2021, Allen was recognized as the top Division I assistant coach in America. With previous stops at Houston, Florida International, and Tulane his 15 seasons of experience in college baseball are as comprehensive as any you’ll find. What he knows about baseball and pitching is tried and true.

While presently working with an acknowledged young staff at Ohio State, he’s in the midst of drawing upon that past experience with four freshman, a returning sophomore, and two transfer sophomores pitching at the Division I level for the first time. And those seven pitchers are the core of a staff that’s thus far pitched the Buckeyes to a 23-22 record and in the hunt for a Big Ten Tournament bid.

Like everyone in baseball, he acknowledges that throwing the ball across the plate – strikes – is where pitching begins, or ends. So we asked…why does it come easier for some than others?

“So many pitchers today are out there chasing numbers – velocity,” says Allen. “Young pitchers believe that you have to have velocity to pitch.”

“If I had the answer of how to throw strikes I’d be a rich man,” he smiled. “I think the biggest thing is to repeat what you do – a repeatable delivery. When you have a repeatable delivery, the same mechanic every time, it makes throwing strikes easier and more simple. And a lot of it comes down to mindset.

“So many pitchers today are out there chasing numbers – velocity – and trying to do more than they can. It’s important to understand that if you have good mechanics the fastball will come. Our sophomore Blaine Wynk had never pitched at the Division I level, and yet his fastball can be 94 to 98 at maximum velocity. But he has some of that old-school mentality, too, when he backs off a bit to just throw a strike. When he does that he can still throw it 90 miles per hour and spot it for a strike.

“It’s also important to understand that you have to pace yourself. If you’re a starter it’s hard to throw it as hard as you can for seven innings. If you’re a reliever you can go full out for an inning.”

When he speaks in these terms he sounds a lot like former Atlanta Braves pitching coach Leo Mazzone, credited with developing Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz…three hall of famers.

Huffer Chiropractic can help your athlete perform at their best – with offices in Osgood, Jackson Center, and Dublin, Ohio.

“Throwing the fastball is a violent arm action when you try to throw with maximum effort on every pitch,” Mazzone says. “It’s hard to do for young pitchers and maintain the kind of muscle memory skills (mechanics) necessary to be a consistent strike thrower. As you begin to tire you lose some of that muscle memory. And personally, I don’t care how hard a pitcher throws.”

Allen concurs.

“Velocity is the state of where we are in baseball,” he adds. “Again, it’s a mindset in young pitchers who believe that you have to have velocity to pitch. They look at the big leagues and every pitcher there is throwing harder and harder. But in the big leagues they can throw it a hundred miles per hour and still throw 60% strikes. They’re big leaguers for a reason. What young pitchers don’t realize that 90 miles per hour now is not necessarily a swing-and-miss fastball. So you have to have command of a secondary pitch. You’ve got to be able to get hitters off time and actually pitch. The guys that can manipulate the ball and the strike zone are the ones who truly have success at this level of college baseball.”

Allen also confesses that it’s possible to throw too many strikes, making it easier for the hitter to anticipate and time up a pitch within the strike zone.

“Our guys who have the most success are the ones who can get ahead in the count, and ultimately make a hitter chase,” he says. “Again, it comes down to command where you change a hitter’s timing and comfort. Today, if a young pitcher can hit 93, but gives up a couple of home runs in the inning, he still thinks he’s had a good day. Instead of going out there and having three up and three down by commanding 88 mph quality pitches in the strike zone, they’d much rather hit 93 and put it out there on social media. Like I said, it’s just where we’re at, but I think we have some guys [at Ohio State] that have a different mindset.”

You’re not going to be successful all the time, which Allen acknowledges, and shares the mindset of how long you dwell on a bad outing before preparing for your next one.

“You have to have a short memory, positive or negative,” says Allen. “And prepare for your next opportunity.”

“You have to have a short memory,” says Allen. “You’re going to have bad outings, but the next day it’s important to have a good attitude. I tell guys all the time that win or lose, you’ve got twenty hours, whatever, to get to the next day and start preparing for the weekend, in our case…or your next start, or opportunity. You can’t spend too much time on the positives or the negatives. You have to be the right kind of kid, be a team guy, and trust what you’re doing.”

And coaches at the next level are usually quick to point out that talent aside, the players they’re developing presently were very recently high school pitchers. So they’re dealing with many of the same issues – positives and negatives – that you’re dealing with.

“We never get done with teaching because there’s always so much to learn,” says Michigan State’s Jake Boss.

A year can make a big difference…for Chase Herrell (freshman from Milford), Gavin DeVooght (freshman from Walled Lake, Michigan), Zach Brown (freshman from Santa Ana, California), and Jake Michalak (freshman from North Royalton, Oh).

A year ago they were walking in your shoes.