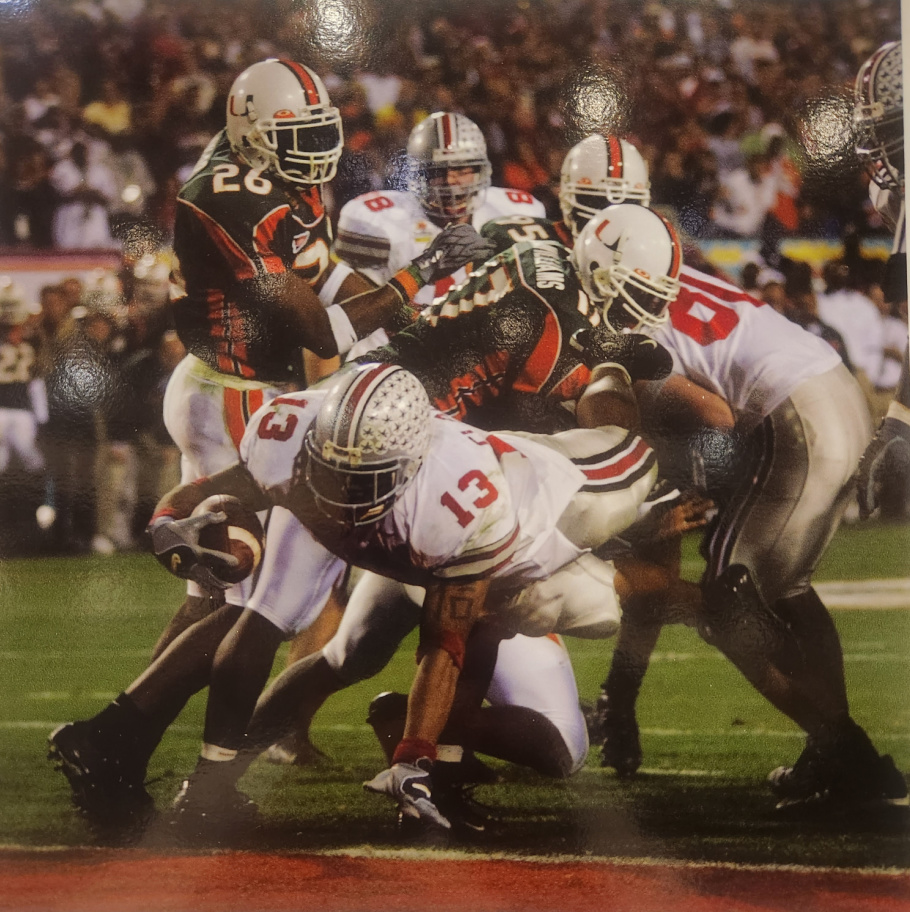

Neal Lauron’s classic photo of Maurice Clarett diving into the end zone for the winning touchdown in Ohio State’s national championship victory over Miami…the photo is iconic…the story behind it is inspiring.

PressProsMagazine.com’s Bruce Hooley was among those the late Neal Lauron asked to speak at his Celebration of Life service on Sept. 30. Bruce spoke about Neal through the prism of one night in his career as a Columbus Dispatch sports photographer. You certainly know the photograph. Now you know, the story behind it, and the type of man who gave Buckeye Nation the perfect photo on a perfect night in the desert two decades ago.

Columbus, OH — I cannot accurately tell you about my friend, Neal Lauron, without referencing a night in both our lives when we were very far from Central Ohio.

Columbus, OH — I cannot accurately tell you about my friend, Neal Lauron, without referencing a night in both our lives when we were very far from Central Ohio.

Neal, a Dispatch photographer, and me, the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s OSU football beat reporter, were casual friends in that era. We’d see each other at games each week and exchange pleasantries like professional colleagues do.

Over the last three years, after Neal contracted 911-related cancer from his work in New York City following the 9-11 terrorist attacks, we became very close and shared many deep conversations.

In one of those talks, Neal told me the story of the iconic photo of Maurice Clarett, diving into the end zone for the winning touchdown in Ohio State’s 2002 national championship victory over Miami.

I always knew the photo was great.

I never knew until that day over breakfast in West Columbus that the story, and the man behind it, were even greater.

It’s one of those rare photos that epitomizes perfection in timing, execution and story-telling…the kind another photographer might take once to forever set a the standard as the best of his work. But in Neal’s case, it was the kind of photograph he took so often that the depth, texture, variety and impact of his talent is what came to define his work.

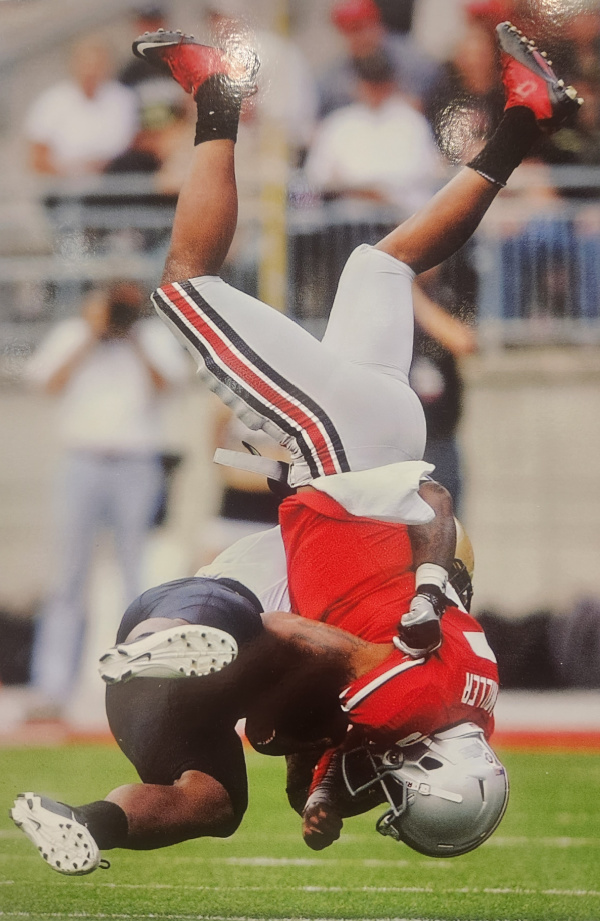

Troy Smith may have lost his helmet, but Neal Lauron never lost his head under pressure, capturing this unique image of OSU’s 2006 Heisman Trophy winner. (Photo courtesy of Lauron family, via Columbus Dispatch).

Almost every Ohio State fan instantly knows the photo, because so many Ohio State fans of that generation have it hanging somewhere in their Buckeye room.

Shooting a photo so distinctive results from a confluence of factors….a snap of the shutter at the exact right time and flawless positioning to capture the image. It also takes the perfect lens to frame the action, and pristine focus. In other words, lots of preparation and professionalism, which Neal required of himself in everything he did.

He told me his night started by doing something he had never done before…something that just isn’t done at mob scenes like national championship football games where there are two or three times more photographers than optimum available spaces to accommodate them.

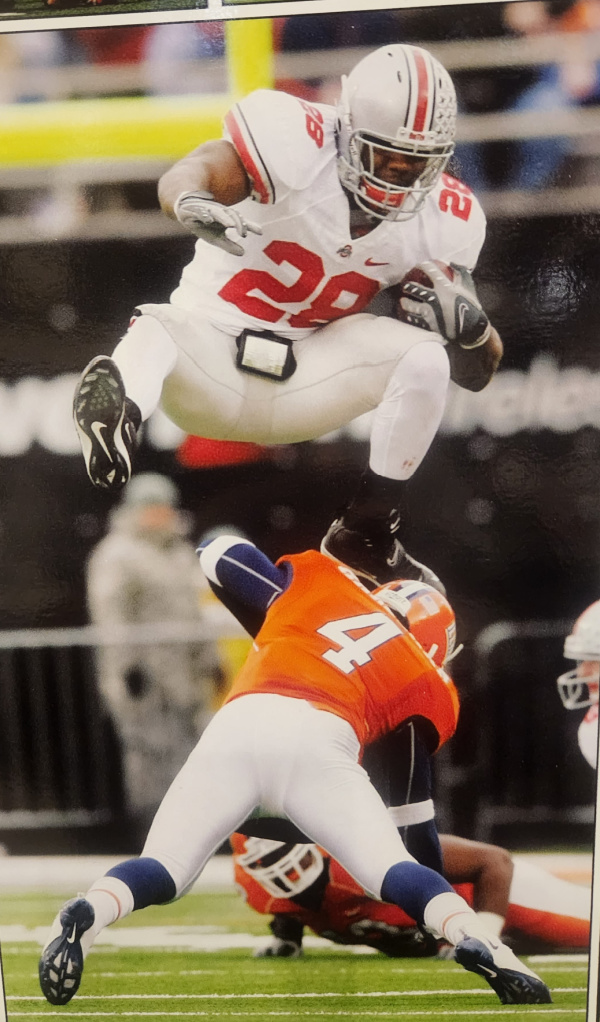

You couldn’t get one over on Neal Lauron’s fast shutter, no matter how high Beanie Wells’ jumped. (Photo courtesy of the Lauron family, via the Columbus Dispatch).

Neal arrived early, and he took a roll of duct tape out to the field. He picked a spot in the end zone and taped off a space just big enough to hunker down on his haunches and snap away. On a routine Buckeye game on a Saturday in Columbus, where Neal would have had cache because of the high esteem in which he was held by his colleagues, this would have been seen as a bit odd and a break from proper protocol.

But in a national championship environment, on sidelines filled not just with photographers and videographers, but glad-handers and hangers-on of every sort from every aspect of celebrity culture, an unknown local newspaper photographer from Columbus, Ohio staking out his own private 3×3 space for others to respect and reserve solely for his use was absurdly ridiculous.

But as Neal explained to me in that distinctive, high-pitched voice of his, “What the heck man. Might as well give it a shot.”

So Neal taped off his spot and then returned to the photo area to set up his laptop and prepare to eventually transmit his digital images back to Columbus. An hour or more later he returned to the field for kickoff and was stunned the space he had taped off was still there and waiting for him.

The game began, and Neal began working. It was a great game, a close game, and at halftime Neal and the team of Dispatch photographers raced to the back of the stadium and begin transmitting their photos. Neal was in rhythm, getting his photos back faster than anyone, about to sprint back to the field for the second half when an on-site editor pulled him aside.

Want a greener, healthier lawn? We can help. contact Weedman USA at 614-733-3747 or go online to Weedman.com.

“Since our deadlines are brutal and since you’re the best and the fastest we have at transmitting photos, could you please stay back here for the second half and transmit other people’s images so we have everything we need when the game ends.”

Neal was stunned. And crushed. The biggest game of the best season in Ohio State history in decades, and they wanted him to shelve his enormous creative talent and transmit other people’s work without shooting any more photographs of the game himself?

He pondered the request and told me what he wanted to say in response: “Don’t you know…I’m the man?”

“It was the kind of photograph he took so often that the depth, texture, variety and impact of his talent is what came to define his work.” (Photo courtesy of the Lauron family, via the Columbus Dispatch).

Instantly, Neal said, he felt convicted over his ego rising up, and so he agreed. He would transmit the photos of his colleagues, fighting the temptation to agonize over every peak and valley in momentum he couldn’t capture on his on camera array, as the game approached a pulsating finish.,

Field goal, Miami, we’re tied…. Overtime! Miami wins!…Wait, there’s a flag. No, they don’t…We’re tied again…Double-overtime!

Neal grabbed one camera with a standard lens, small enough he could secure it easily, like a football under his arm, as he sprinted back to the end zone.

He’d been gone for well more than 90 minutes, but, amazingly, his spot was still there. No one else was in it.

Neal crouched down beside other photographers from around the country with their mammoth telephoto lenses, all of whom were no doubt wondering, “What does this dude think he’s going to do with that little thing?”

The second overtime started with Ohio State in possession, and the handoff went to Clarett. Neal clicked the shutter and paused to consider what just happened. In moments like these, there is an instinct which only the great creative artists have. Neal had that instinct, and it told him, “You got the shot.”

But just to be sure, he checked the viewfinder on his camera.

He indeed had the shot.

Polaris Pools is proud to sponsor coverage on PressProsMagazine.com. To inquire about a beautiful Polaris Pool in your backyard, go to shearerlandscaping.com/polaris-pools/

This would have been a really tempting time for Neal to exult to himself in triumph, “I told you…I’m the man.”

But instead, he reacted quite differently.

He broke out in tears and began weeping openly.

Why?

Neal told me he realized in that moment that what mattered was not the glory he would receive from taking the photo that perfectly

summarized the thrilling events of that night. What mattered to him was proof of how things worked out because he chose to do the sacrificial thing, rather than the selfish thing.

As Neal finished his remarkable story, I could offer little in return other than to say, “Wow, what a story.”

Now you know the story, too. And if that prompts you to express your posthumous appreciation for Neal’s work, and for the kind of man he was, you can contribute to the Neal Lauron Memorial Scholarship Fund for one graduating Grove City Christian School student each year with plans to major in the arts (photography, music, graphic design, etc.).

Paste this link into your browser to donate to the Neal Lauron Memorial Scholarship Fund: https://pushpay.com/g/thenaz?fnd=7VRZIv9eJXZOfQns6eC08g&lang=en&src=pcgl