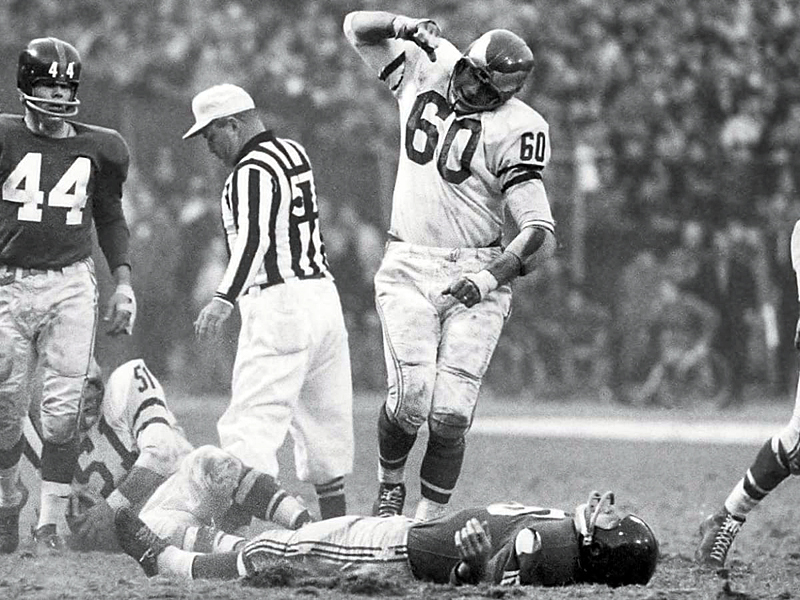

Gruesome as it seems to some today, our heroes were the players we watched on the weekends. We wanted to be just like them. (From Private Collection)

We grew up as kids who entertained ourselves. It wasn’t always pretty, or safe by today’s standards…and it wasn’t appreciated by the local evangelicals. But in the end it’s what we did for fun, and most of grew out of busted lips and chipped teeth…grew up to be just fine!

Cincinnati, OH – It didn’t fit. It seemed completely out of place.

Cincinnati, OH – It didn’t fit. It seemed completely out of place.

A bunch of kids—maybe a dozen or more—were gathered in a large field. The field was bordered on one side by a major thoroughfare and on the other by a slew of buildings, some new and shining, some old and nearly spent.

I was caught at the intersection waiting on a light surrounded by four lanes headed east, four headed west and three more coming in from the north. It was 4:30 in the afternoon. Traffic was thick and angry, every body dead-bent on where they wanted to go, where they wanted to be — and every one else, be-damned!

My attention had first been drawn to the kids as I approached the stoplight. It looked like it might be a fight, but maybe not. What was it? I couldn’t figure it out.

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Post…popular for his stories of sports nostalgia.

Then, just as the light turned, engines roared and a horns started to bark and blare, I realized what was going on. Right away, I started looking for a place to get off the road so I could get a better look. There were errands to run but they could wait. This was worth a longer look.

I worked through traffic, made my way around the block and found a parking lot near the field, and right there, right in front of me, there it was: kids playing old-fashioned tackle football, no uniforms, no pads, no coaches, no parents, no holds barred, just good old-fashioned tackle football. In my mind I could see Vince Lombardi in his tan overcoat walking the sideline at Lambeau Field, yelling at the top of his lungs: “Just what the hell is going on out there?”

As I stepped out of the car, a ball carrier was grabbed by the back of his sweatshirt and spun to the ground. He stood, laughing and threw a friendly jab at the kid who had tackled him. Like the rest he was maybe 10 or 12 years old; like the rest he was grass-stained and mud-splattered head-to-toe.

I leaned against my car just watching, listening to them talk and yell.

“I’m Joe Burrow.”

“Yeah, right! You throw like your mother.”

“Yeah, well you know what you can do.”

For part of an afternoon, they were their heroes:

“I’m Ja’Marr Chase.”

“Yeah, right. Well, I’m Tyreek Hill. Eat my freakin’ dust.”

They were having fun but they were serious, too. They were friends, but in moments tempers flew. They pushed. They shoved. They cursed. But the game went on.

For part of an afternoon, they made an aging man very happy. I got back in the car and left the boys to their game and their dreams.

All the way home, the memories the game had stirred kept coming, filled with the faces and voices from the past, the gang from back home. I could see them clearly: Sammy “Soup” Campbell, Big Dave Crane, the Stutsman brothers, Pete “Bad” Byrne, Shep, “Ol’ Lefty” and so many others whose names had faded with the years that had passed.

Baseball was our game. We lived baseball and basketball was a close second. But when it got cold and nasty and the ground was frozen or turned to mud from the melting snows, we played tackle football.

Back then in Blocher, a tiny little town in the southern most part of Indiana, we hadn’t heard of flag football or touch football. We only knew the football we saw on TV, the hard-nosed game that belonged to our heroes: Jim Brown and Johnny Unitas, Paul Hornung, Frank Gifford, Ray Nitschke, Sam Huff, Bobby Layne and, or course, Dick “Night Train” Lane and Max “Party All Night” McGee.

Back then in Blocher, a tiny little town in the southern most part of Indiana, we hadn’t heard of flag football or touch football. We only knew the football we saw on TV, the hard-nosed game that belonged to our heroes: Jim Brown and Johnny Unitas, Paul Hornung, Frank Gifford, Ray Nitschke, Sam Huff, Bobby Layne and, or course, Dick “Night Train” Lane and Max “Party All Night” McGee.

We could run. We could throw and most of us could take a lick. We fought. We cursed. There were busted lips here and there and Sammy chipped a front tooth. But when the game was over, no grudges were held. We were buddies and we’d head over to Raymond’s, our hangout—much to the owners’ dismay.

Raymond’s was half gas station, half grocery store and if you had a quarter in your pocket, you could get a Coke, a Hershey bar and a bag of chips. For 50 cents, Raymond would make you a baloney and cheese sandwich on white bread — of course.

Our problem back then was finding a place to play, and in a strange way that led some of us — well, me anyway — to a loyalty that lasted for decades.

For a while, we played behind the old, abandoned two-room schoolhouse that many of our parents had attended. But there were rocks in the field and broken glass, even chips of coal. So, we moved to the big lawn behind the Methodist church.

The grass there was thick and plush and somehow the ground was seemed almost soft when you were tackled or knocked down. It was a great place to play, all we needed or wanted and close to Raymond’s, too.

I don’t remember how long we played there, but I do remember the solemn night my mother sat me down after dinner and told me we couldn’t play there any longer.

“There have been complaints about you boys fighting and cursing,” she said.

Seems the minister had spread the word to our parents that the church viewed our game and our behavior as unacceptable. Consequently, we were “banished”.

“Besides,” Mom said, “you’re killing the grass. They say.”

“Banished,” Mom said, shaking her head. “Complaints from members of the parish. Can you imagine?”

Dad looked at me and chuckled. “Criminal,” he said, smiling.

Within one short season we managed to be banished by both the local Baptist and Methodist churches.

Come to find out, the Post Mistress Miss Belle Webster, a very proper old maid and a pillar of the church, had led the charge against us. Her house was just across the street from the churchyard and she had taken her complaints of our fighting and cursing to the minister.

Word came round that we were a bunch of “hooligans” who spoke like “sailors on leave.” Every gossip-monger in town was whispering about our behavior.

After a few days without a field, Big Dave suggested we play at the Baptist church just about a mile out of town. But, apparently word had spread.

We jumped on our bikes and headed out, many of us riding double, but we had no sooner gathered in the parking lot than Brother Kern, the reverend there, burst through the front doors.

You would have thought we were a gathering of demons; that young warlocks had darkened his doorstep.

“No, sir,” he railed. “Be off with you. We’ll have none of your shenanigans around here. Bunch of little troublemakers. Your behavior is beneath this place and won’t be abided on these grounds.”

He had us all but doomed to perdition when Shep, more informed and outspoken than the rest of us, interrupted.

He had us all but doomed to perdition when Shep, more informed and outspoken than the rest of us, interrupted.

“Brother Kern,” Shep said, “we’re only playing tackle football. Hell, we could be dancin’. How ‘bout that?”

Of course, this didn’t go over very well, so we sped off on our bikes, a tackle football team without a place to play but a happy bunch, nonetheless.

Of course, being a tiny little town, word of the incident with Brother Kern had spread by dinnertime. Dad and Mom and I talked it over, Mom — our family representative at the Methodist church — doing most of the talking, and after a while everyone sat quietly.

Finally, my dad folded his napkin, sighed and said, “Well, boy, you been banned by the Methodists and the Baptists — not wanting you to play on their property.

“Leads me to one thought,” he continued. “The Catholics must have an entirely different view of football.”

I looked at him, not understanding the grin coming to those dark eyes.

“Why, don’t you understand, boy,” he said. “Look at Notre Dame and all they’ve done.

“Besides,” he went on, folding his newspaper, “baseball season ain’t that far away.”

In the days that followed, my dad and his friend Dike, a drinking buddy, cleared out a field behind an abandoned barn near my grandpa’s garage. That’s where we played for some years and where, over time, I figure, many of us became Notre Dame fans—one way or another.