Yesterday was Jackie Robinson’s birthday, and much was again made of his breaking the color line in major league baseball. But I wish they would tell the entire story of breaking the color line, because I think Larry Doby’s family (and history) would appreciate it.

In my best imitation of Hal McCoy and his gift for telling the rest of the story…yesterday was the anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s birthday. Robinson, of course, was the man who broke the color line in major league baseball when General Manager Branch Rickey brought him to the big leagues in 1947 to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In my best imitation of Hal McCoy and his gift for telling the rest of the story…yesterday was the anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s birthday. Robinson, of course, was the man who broke the color line in major league baseball when General Manager Branch Rickey brought him to the big leagues in 1947 to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The story of what Robinson endured, his perseverance on behalf of African-Americans and other minorities who would eventually make it to the major leagues, and for equality across the scope of culture is well-documented.

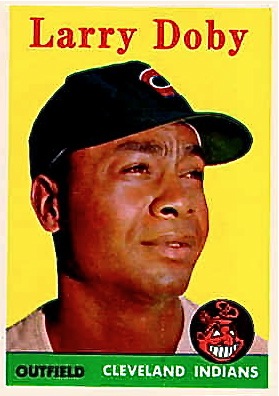

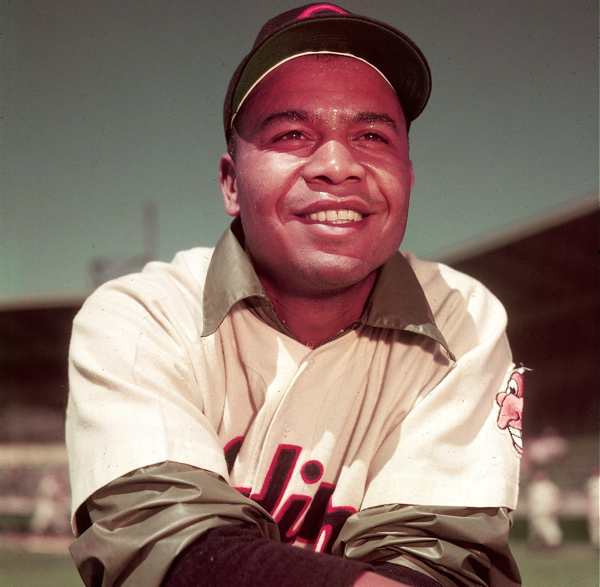

But what’s lost in history, what’s never mentioned in the same breath with Robinson, is the fact that another African-American named Larry Doby came to the big leagues that same year to play with the Cleveland Indians three months later, on July 5, 1947.

But what’s lost in history, what’s never mentioned in the same breath with Robinson, is the fact that another African-American named Larry Doby came to the big leagues that same year to play with the Cleveland Indians three months later, on July 5, 1947.

Doby was every bit as good a player as Robinson. In fact, their career numbers are very similar. Robinson hit for higher average (.313 to Doby’s .287), but Doby played longer than Robinson (15 seasons), hit 273 home runs (Robinson hit 141), and drove in 1,094 (Robinson had 761).

Doby was a quiet man who really didn’t talk much about being the first black player in the American League. Compared to the more public Robinson, he was a humble, quiet guy who endeared himself to teammates and contemporaries for his ability to play big in big situations. He hit .300 twice in his 15-year big league career, and seven times hit twenty home runs or more, his best years in ’52 and ’54 when he clubbed 32 for the Indians.

But it was Robinson who captured the headlines because he was the first in the major leagues…and more outspoken in later years for the sake of racial equality not only in baseball, but the country, as well.

Robinson was out of baseball by 1957, two years before the Dodgers would move west to Los Angeles.

Robinson was out of baseball by 1957, two years before the Dodgers would move west to Los Angeles.

Doby retired in 1960 and would go on in baseball as a scout and coach, and in 1978 he became the second black manager in major league baseball when owner Bill Veeck hired him to manage the Chicago White Sox. He finished out the ’78 season with the White Sox, compiled a 37-50 record with a horrible team, and was replaced in 1979 by Don Kessinger. He retired from baseball, officially, after the ’79 season.

But none of this do you hear about. I met Doby along the way in the spring of 1977 when he was the White Sox’s hitting coach. Curious, I asked him about his past and time with Cleveland, and listened to others’ attempts to get him to comment on being the American League’s black player in 1947. There was a sense of irritation from Doby, whether he was just tired of being asked or the fact that he didn’t get the attention he rightly deserved. But he would calmly say, “Jackie was the first, and he deserves the attention.”

Jackie was the first, indeed. And he did deserve the attention. But Larry Doby was just as good, just not as big a figure or publicly bitter about playing through the very same prejudice that Robinson endured. And for that he deserves the same attention. I doubt if I, or other baseball fans, will live long enough to see it. But I’d like to.

There was a recent post on Facebook from Roger Clemens, shared with me, where Clemens’ attempts to put his Hall of Fame snub out of mind and out of the yearly attention of baseball media.

Said Clemens: “Hey y’all! I figured I’d give y’all a statement since it’s that time of the year again. My family and I put the HOF in the rear view mirror ten years ago. I didn’t play baseball to get into the HOF. I played to make a generational difference in the lives of my family. Then focus on winning championships while giving back to my community and the fans as well. It was my passion. I gave it all I had, the right way, for my family and for the fans who supported me. I am grateful for that support. I would like to thank those who took the time to look at the facts and vote for me. Hopefully everyone can now close this book and keep their eyes forward focusing on what is really important in life. All love!

Said Clemens: “Hey y’all! I figured I’d give y’all a statement since it’s that time of the year again. My family and I put the HOF in the rear view mirror ten years ago. I didn’t play baseball to get into the HOF. I played to make a generational difference in the lives of my family. Then focus on winning championships while giving back to my community and the fans as well. It was my passion. I gave it all I had, the right way, for my family and for the fans who supported me. I am grateful for that support. I would like to thank those who took the time to look at the facts and vote for me. Hopefully everyone can now close this book and keep their eyes forward focusing on what is really important in life. All love!

Personally, I can’t question him making a generational difference for his family, his passion, or what he did to give back to his community and his fans.

But I can share an experience of what he didn’t give to a group of fans when I once ran into Clemens’ at a Florida restaurant, introduced myself, and mentioned that I was from the Miami Valley – Dayton, Vandalia, and Troy. He said nothing, and pushed past a small group of people standing nearby who wanted to, but were afraid to ask him for an autograph.

What I wish is this. We all have bad days, or course. But try to remember some of them when you post insincere crap on Facebook. It’s really hard to believe that you can win 354 big league games and you’ve put the HOF fame out of your mind…because people believe you juiced. In his case the rear view mirror is, in fact, the windshield to his future.

Pretty much like saying, “All love!”, with an exclamation point.

Larry Doby was the first black player in the American League, played 15 seasons, and hit .287 and 274 home runs. He later was the second black manager in major league baseball. (Press Pros Feature Photos)