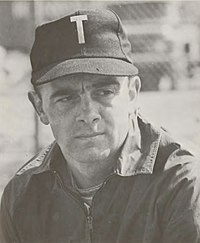

I knew him for four developmental years of my life. And while they weren’t all good years, I learned something from former OSU baseball coach Dick Finn that’s universal about school, sports, business…and life.

I got a text from a former Ohio State baseball teammate, Jim Haney, Tuesday morning informing me that our assistant coach back then (1971-’74), and later the Buckeyes’ head coach, Dick Finn, had passed away.

I got a text from a former Ohio State baseball teammate, Jim Haney, Tuesday morning informing me that our assistant coach back then (1971-’74), and later the Buckeyes’ head coach, Dick Finn, had passed away.

Finn was 88, and I knew he had been in poor health for some time.

He grew up in Allen County, Ohio area and was an outstanding high school pitcher for St. Rose School, in Lima. He came to Ohio State to pitch for Marty Karow in 1954 as Karow sought to make the Buckeyes relevant in something besides football. Having built Texas A&M into a perennial Southwest Conference champion, Karow left A&M in 1950 to return to Ohio State, where he had played baseball and football in the 20s.

Finn was a little, wiry guy who had a reputation back then for being a hard thrower…and one that could throw hard all day long. He once told me he was taken out of a college baseball game just once for a relief pitcher…and was embarrassed that it happened.

Dick Finn coached at Ohio State from 1970 through 1987.

But by the late 60s he had risen as a coach at Toledo University and came back to Ohio State in 1969 as Karow’s assistant, in charge of pitchers. And when I arrived in the winter of 1970 all Finn knew about me was what he had read in a letter of recommendation from my American Legion coach in Troy, Ohio, Frosty Brown.

“Frosty says you can throw strikes and get people out,” said Finn during our first meeting. “If you can we’ll take a look. If you can’t, we have enough people like you already.”

This was just five years after the Buckeyes had won the 1966 NCAA national championship, but the program was a far cry from that group that included Steve Arlin, Arnie Chonko, Chuck Brinkman, and Bo Rein. So I showed up at French Field House to throw during indoor scrimmages.

I did throw strikes, and I got some people out. But Finn and Karow were both concerned that I didn’t throw ‘Big Ten’ hard, as Karow called it. Still, they gave me a roster spot in the spring of 1971 and took me on the pre-season trip to Coral Gables, Florida. There I got a real education on the difference in pitching to high school and Legion hitters and those at the next level trying to make an impression on major league scouts. However, I got enough outs, and pitched well enough for OSU to keep me around. I made three varsity appearances that season, and got this assessment from Finn at the end of the year.

“We think you’re going to grow and get stronger. And when you do I hope you come back with a better fastball.”

By the following year I did get bigger and stronger, but I didn’t throw significantly harder. Still, Finn gave me a chance to pitch as a sophomore and I led the team in wins, innings, and strikeouts. But I couldn’t do it in the manner expected, and by my junior year I had lost ground. It was then that I went to him for a fateful meeting.

“We just think the new kids we’re recruiting give us a better chance of winning,” he said. “You need to become more competitive.”

That was hard to understand, given what success I had had, but I wanted to play and I was determined to impress him. I tried a lot of things – everything, in fact. But I never got to the point where I threw ‘Big Ten’ hard. I had some injuries, some anger, and a lot of frustration. Twice during my final two seasons I pitched the second game of doubleheaders with this directive from Finn: “Go as long as you can because we don’t have anyone to pitch in relief.”

Which wasn’t exactly true. It was just Finn’s way of telling me he expected me to find a way to compete. Years later I brought that up to him and he remembered as if it had happened the day before. “Those two games were an education for me,” he said. “I realized you were good with what you had. And I’m sorry I didn’t see it before.”

It’s not as cut and dry now as it was back then. I think contemporary college baseball is more receptive to different styles and types of athletes now. But the one thing that hasn’t changed is that which defined Dick Finn. You have to compete in life; and not just give it lip service.

You have to earn the respect of both teammates and opponents, and it doesn’t matter if it’s a baseball team or the workplace. That’s what I learned from him – that sometimes you have to hear some hard things. We all learn later than we should about life, and I made sure he understood that I knew that the last time we talked.

You have to earn the respect of both teammates and opponents, and it doesn’t matter if it’s a baseball team or the workplace. That’s what I learned from him – that sometimes you have to hear some hard things. We all learn later than we should about life, and I made sure he understood that I knew that the last time we talked.

He nodded with that smile of his that meant he appreciated it as a compliment. And it was a compliment, because it happens to almost everyone in life, no matter what you do. We don’t all throw 90. Sometimes you have to find another way.

And somebody has to tell you.