Baseball and time change, as do the voices we come to depend on to describe the action. Too much change, for some of us, I fear. It’s been two years since Marty left. It seems…like light years.

Like many others around here, this Reds team has captured my interest like none other in a long, long time. And, like a lot of others, from what I gather, I enjoy keeping up on their progress by listening to the games on radio rather than watching television.

Like many others around here, this Reds team has captured my interest like none other in a long, long time. And, like a lot of others, from what I gather, I enjoy keeping up on their progress by listening to the games on radio rather than watching television.

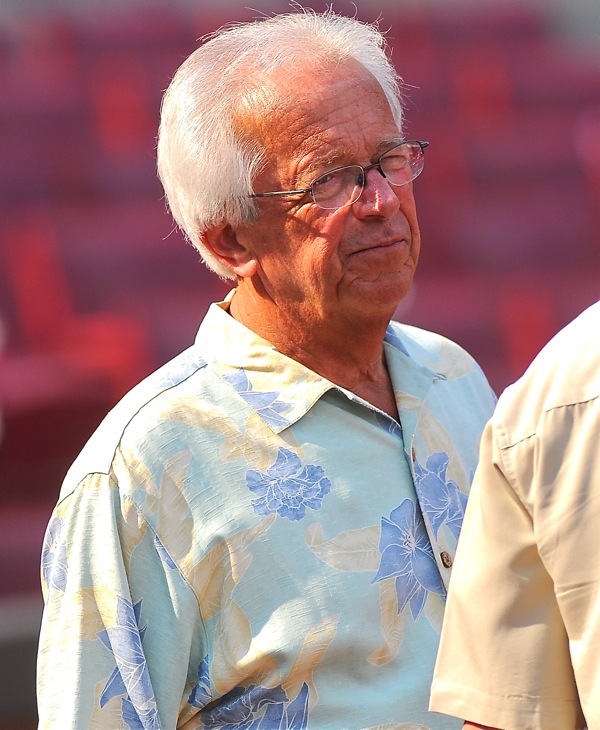

To a degree I think this is a product of the past, a matter of habit. For more than 40 years, Marty and Joe on the radio was synonymous with Reds baseball, good years and bad ones. Marty Brennaman and Joe Nuxhall made those bad seasons tolerable, and there were times when they were truly tested. Often, they were the show, the primary reason to tune in.

Why? Well, we could come up with a laundry list, but above all, they were honest. They called the game without indulging in hyperbole or resorting to apologetics, traits that have marked the television broadcast for years.

While members of TV teams often regaled the efforts of those bottom-feeders, Marty and Joe gave us a broadcast without guile.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

Fact is, Marty and Joe spoiled us much as the Reds great teams of the 70s spoiled those of us old enough to remember The Machine. Teams like that don’t come around very often. You are darn right lucky if one lands in your generation.

This brings me to the current radio team of Tommy Thrall and Jeff Brantley. They are pretty good together, especially when Brantley slips it back into low and remembers what got him where he is and with whom he studied and learned. They are a young team and with time I think they will get better.

But, in the meantime, there are some things that need to be fixed and the sooner the better—for them and certainly for their listeners.

Foremost, this constant over-analysis of every pitch in the game, every movement—in, out, up and down—has got to stop. It’s too much. I get dizzy trying to visualize what’s going on, and I can’t imagine anybody hitting what they’re describing.

It’s sounds like a graduate school course in pitching: Pitching 400 in your syllabus, the study of pitching paired with astrophysics.

In most cases they are talking about miniscule movements, along with a lot of would’a, could’a, should’a stuff.

Well, he started that ball on the outside corner taking a little off the pitch, thinking it might run back across the plate and take a dive down and out of the strike zone, which often happens when he throws that four-seamer, but this one stalled out, hung back and ended up right down the pipe and there ya go, home run.

I can buy some of this from Brantley. He was a big league pitcher for 14 seasons, a good reliever, winner of the Rolaids Relief man of the Year in 1996. He knows the craft, but I don’t remember him dwelling on pitches as much when he partnered with Brennaman.

I can buy some of this from Brantley. He was a big league pitcher for 14 seasons, a good reliever, winner of the Rolaids Relief man of the Year in 1996. He knows the craft, but I don’t remember him dwelling on pitches as much when he partnered with Brennaman.

For my money, Brantley is best when he’s hunkered down behind the microphone talking baseball, sharing his insights and telling stories, even if its about his latest haul down to UDF for a strawberry sundae or his latest faceoff with a plate of fried chicken and a bowl of biscuits.

As for Thrall, he jumps on this pitch thing willy-nilly, and sometimes I get the impression that Bugs Bunny is on the mound, or at the very least, the pitch was thrown with a Wiffle ball.

That pitch started out on the outside corner, cut across the plate and then went down and in and into the dirt and I can’t believe the umpire didn’t call it a strike.

We don’t need all this. Balls and strikes, that’s all we really need to know. That’s what we want to know.

Granted, if a particular pitcher is known for a particular pitch—Steve Carlton and the slider, for instance, Mariano Rivera and the cutter or Bruce Sutter with the split finger—then, of course, we want to hear about it, but even then not over and over, ad nauseum.

In fact, all the attention to different pitches gets a little tiresome. I don’t especially care if it was a two-seamer, four-seamer, slider, cutter or curveball. I don’t much care if it came through the back door, front door or a bathroom window—apologies to Joe Cocker.

As for Thrall, he’s a hard worker, knows the game and obviously loves his job. But I sometimes get the feeling he is paid by the word. He makes me think of an expression my grandmother sometimes used when she encountered a talkative sort: “He surely likes the sound of his own voice.”

Over the years I had the opportunity and privilege to interview many of the great announcers: Vin Scully, Jack Buck, Harry Caray, Ernie Harwell, Harry Kalas and Pee Wee Reese, among them. I am proud to say Marty Brennaman is a good friend, and I was fortunate enough to write Joe Nuxhall’s biography. All these guys had one thing in common, and they talked about it all the time. They let the game breathe. They gave it space.

Over the years I had the opportunity and privilege to interview many of the great announcers: Vin Scully, Jack Buck, Harry Caray, Ernie Harwell, Harry Kalas and Pee Wee Reese, among them. I am proud to say Marty Brennaman is a good friend, and I was fortunate enough to write Joe Nuxhall’s biography. All these guys had one thing in common, and they talked about it all the time. They let the game breathe. They gave it space.

Nuxhall said it very well. “It took me years to understand that you don’t have to talk all the time. Feel like you got to say something about every move. You don’t want to crowd the game. Hell, that’s the reason we got those microphones out the window. People want to hear the sound of the game, not me yappin’ away.”

Towards the end of his illustrious career, Scully said: “After all these years I am still guilty of getting lost in a story or a memory. But, in the end, you must always be aware that the game is the thing. That’s the show. You are not the show. Let the game speak. It often tells a marvelous story all by itself.”

Of course, it’s only fair to point out broadcasters of such stature operate on a much longer leash than relative newcomers. I once ask Thom Brennaman why he was so much better doing a national game than he was doing a Reds game, whether it was on radio or TV.

He looked me dead in the eye and said, “You think so? Well, you have to remember I am an employee of the Reds and the game is our product.”

“So, you are a salesman of sorts?” I said.

He didn’t answer me. He didn’t have to. He only smiled.

For now, I’m buying the Brantley/Thrall tandem. I just wish they would lean back a little and shift it into low.