Sign of the times? There was a time when you went to a major league game to learn, not be entertained or to hear a statement on political correctness. You went because you were interested…in baseball!

CINCINNATI—It was early April 1963 and on this particular Saturday afternoon, Crosley Field was bursting with its own brand of beauty.

CINCINNATI—It was early April 1963 and on this particular Saturday afternoon, Crosley Field was bursting with its own brand of beauty.

The grass seemed greener, the sky more blue. Even the dirt in the infield seemed prettier and better than any dirt anywhere else in the world. Back then baseball had a hold on us like nothing else in the world—men and boys, alike.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

Before we had cleared the turnstiles we could hear the sounds of the game: the snap of the ball meeting well-oiled leather, the unmistakable sound of the ball on the bat, that smart crack that split the air.

“See, we’re late,” my uncle said, pressing a through the crowd. “You were dawdling along and now we’re missing batting practice and infield.”

Uncle Bob had specific rules about attending a big league game. They were rules honed by a lifetime in baseball. He was signed by the Yankees out of high school and climbed through the organization to Double-A ball before he was cut loose.

“I was one of those guys who couldn’t hit the breaking ball well enough to make the grade,” he often said, and always there was a note of sadness in his voice.

Along the way he had made many friends and come away with strong feelings about the game and more knowledge than most.

Back then some of his rules seemed silly. Today, I understand. Back then he always dressed for the game: usually, a sports coat or a sweater and nice slacks. He insisted I wore pants. “No jeans,” he said. “No shorts and no sneakers. We’re not going to the damned county fair. We’re going to a big league ballgame.”

We always arrived at the park in time for batting practice and infield no matter the circumstances, no matter who was playing or how things stood in the standings. His reasoning was simple.

“I’ll tell you why,” he said. “Because that’s when you learn, when you see things about players. What they do. What they don’t do or don’t do well.

“Bud, that’s when you can spot one of the most important things about this game—character, whose got it and who doesn’t. That’s when you can tell who wants to work for it and who doesn’t. Talent isn’t always enough. Rarely, is talent alone enough to make it in this game.”

Don Blasingame was the popular incumbent at second base for the ’63 Reds. Pete Rose said to him in spring training, “I’m going to take your job.”

It was a speech I heard countless times over the years. I heard it before every Reds game we attended and every baseball game we watched on television, especially when his beloved Yanks were on The Game of the Week.

When Pee Wee Reese and Dizzy Dean were calling the game, Bob would sit quietly for long stretches then say something like, “It’s a great thing to have a talent like Mickey Mantle, but players like that don’t come around very often. The players who make a team really good are the meat and potato players, the workers who make the most of what they have: (Yogi) Berra, (Bill) Skowron, Bobby Richardson, (Tony) Kubek.

“Don’t misunderstand. They are all talented. But they know what they can do and what they can’t do, and they go out and give it their very best every damned day.”

Then, he would smile and say very slowly: “Look at me. That’s what you’ve got to do, and everyday no matter what level you’re playing. You’re out in the pasture playing ball or on some scrub diamond, you give it everything you got and you empty that tank every time you go out there.”

SO, BACK THEN on that Saturday afternoon in early April 1963, the topic came up again as we settled into our seats a few rows behind the dugout on the third base side of the field, and it came up because of a player who had caused a big stir during spring training, a 22-year-old rookie second baseman named Pete Rose.

“There, number 14,” Bob said. “Some people really like him, and some don’t. Word is he’s pretty full of himself. I heard that early in spring training he walked up to Don Blasingame—a veteran and well-liked, mind you—and says, ‘I’m the guy who is gonna take your job.’ No flipping wonder some guys don’t like him. I’m surprised somebody didn’t drop him on the spot.”

We watched Rose take ground balls during infield and watched him dart in and out of the batting cage during BP. “The kid’s got one gear, high,” my uncle said. “But that’ll wear off with time—if he lasts.”

In those lazy moments before the game started—when the grounds crew put the final touches on the field, watering the infield and touching up the chalk around home plate and down the lines at first and third—my uncle talked with others seated around us, and Rose was the dominant topic. Like the Reds players, their feelings were mixed, as well. Most were adopting a wait-and-see approach.

Personally, I was more interested in watching Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson, who went about their business with such ease, and who seemed, to me, at least, amused by Rose and his boundless energy.

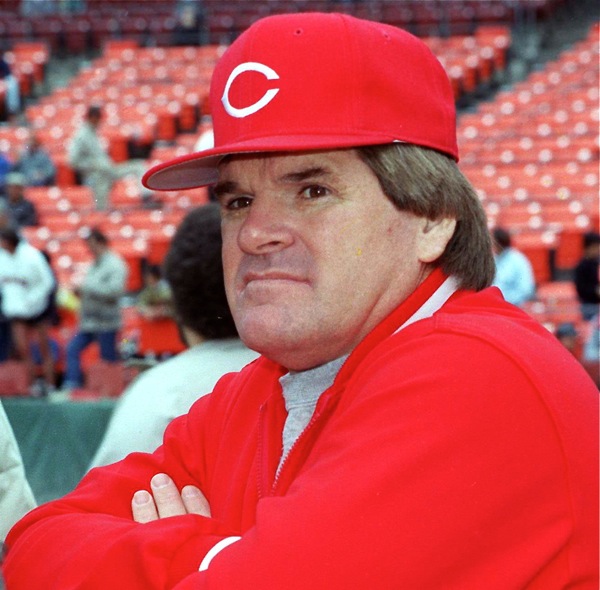

Pete Rose as he looked as a rookie in 1963…and before he was assigned uniform #14.

We started to see more of Rose when Bob Friend hit him with a pitch early in the game. Rose didn’t flinch. He turned and sprinted—sprinted—for first. He hit the bag at full speed and made a turn as if he were going to take second.

“Look out,” Bob warned, “that’s a hotdog move and it won’t go over well. What’s he doing sprinting to the bag? Friend ain’t gonna like that, bein’ shown up like that. He’ll get dusted for sure. Wait and see.”

In Rose’s next at bat, Friend did throw a couple of pitches up and in, but it cost him a walk and again Rose sprinted for first, again taking a big turn before easing back to the bag. Friend stepped off the mound and eyed Rose, whose only reaction was a smile and a tug on the bill of his cap.

At that point, Uncle Bob offered a concession. “I don’t know that I like the little hotdog,” he said. “But he sure as hell has some grit. I’ll give him that. He’s either going to be respected or hated. I don’t know which.”

Before the game was over Rose added a triple to left and scored on a single by Pinson. When the game was over, he was 1-for-3 with a run scored and one of the Reds’ two extra base hits. The other was a home run by Frank Robinson. The Reds lost, 12-4.

“Look at this,” Bob said, pointing toward my scorecard. “Rose was on base in three of his five at-bats.” He considered this for a while, thinking about what he wanted me to see and learn.

“This kid, Rose, is not that talented,” he said. “He doesn’t have an arm. He’s not a burner, but you and all your buds can learn from him. He’s not afraid of a damned thing, and he’s out there bustin’ his butt every minute he’s on the field. He’s got guts and grit. He may never be well liked, but he’ll be respected. I guaran-damn-tee he’ll be respected.”

OVER THE YEARS and before his death last year, Bob and I talked about lots of players. As for Rose, it was somewhere during his 44-game hitting streak when Bob allowed that Rose might last. “Ya think, Bud?” he said, laughing.

He never liked Rose. He preferred players like Stan Musial, Mantle, Carl Yastrzemski and Johnny Bench, those whose play was marked by a quiet excellence. But he admired Rose because he did so much with what he had.

“Everything he does is about winning,” he said. “Look how many times he changed positions to make the team better. Hell, he played third and right field and your grandmother has a better arm. But, he made it work.”

Baseball meant everything to Bob. When we went to Crosley Field we went to watch and learn and savor the efforts of those who had reached the highest point of the game we loved, and no distractions were allowed.

I will never forget a game when a group of guys—probably in their mid-30s—were seated down from us yelling, laughing, stopping every vendor that came along. When we weren’t passing hotdogs and beers down the line to them, we were standing up so they could go back and forth down our aisle to another food booth or the men’s room.

I will never forget a game when a group of guys—probably in their mid-30s—were seated down from us yelling, laughing, stopping every vendor that came along. When we weren’t passing hotdogs and beers down the line to them, we were standing up so they could go back and forth down our aisle to another food booth or the men’s room.

Finally, Bob had had enough. He stood up and yelled: “Hey, boys, did you come here to watch the damn game or to eat your flipping dinner. There’s a bar right across the street.”

A few words were exchanged, but the boys down the aisle watched the rest of the game with a more acceptable deportment, and when they left their seats, they went the other way—the long way around. They may not have liked Bob. I’m sure they didn’t. But I believe they respected him.

Back then, you could learn a lot at the ballpark.

The Buckeye Diamond club is proud to sponsor coverage of Buckeye baseball on Press Pros Magazine.com.