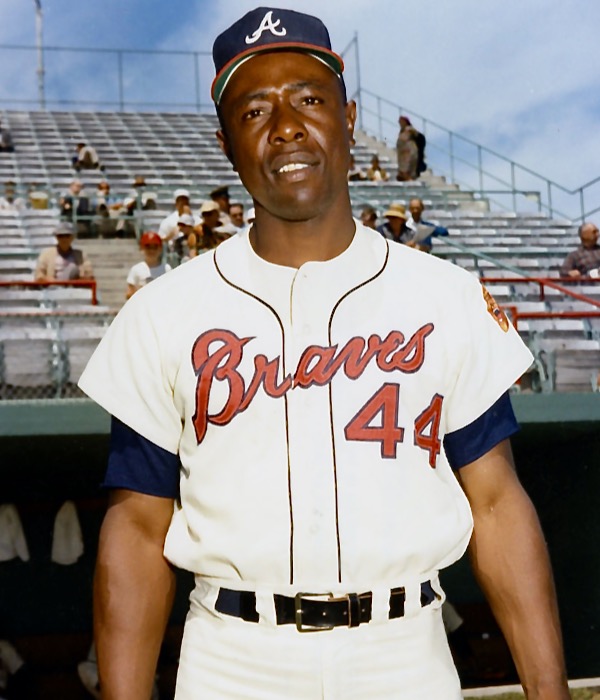

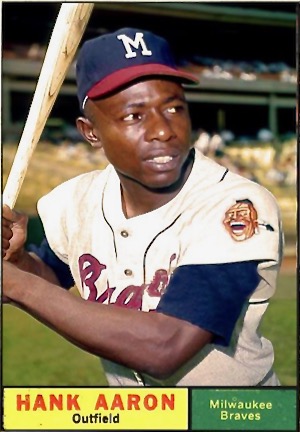

He’s remembered as one of baseball’s legends, and by some…still the all-time legitimate home run king. But I will remember former Braves great Henry Aaron as a really kind and interesting human being who took the time to just talk baseball.

In my fifty years of playing, officiating, and just being a fan of baseball, there are more than a few cherished moments.

In my fifty years of playing, officiating, and just being a fan of baseball, there are more than a few cherished moments.

I threw a pair of no-hitters in the summer of 1970, playing for Frosty Brown’s first (or second, I’m not sure) Troy Post 43 American Legion baseball team. They came within two weeks of each other, against Beavercreek and Miamisburg.

I played baseball at Ohio State, where I walked on during the winter of my freshman year, made the varsity baseball team and pitched four years on the strength of the skills I developed from playing not on some elite summer travel team…but with that same Troy Legion team that played at North Market Street Field.

And after college I took the risk of setting aside the normal career path of working in the public sector…for pursuit of a career in baseball – umpiring seven full seasons in A, AA, and AAA minor league baseball from 1975 through 1981. And it was there, on a night in Orlando, Florida in 1978 that I had one of the best experiences in my baseball life – the night that I actually met, in person, and got to talk with home run king Henry Aaron.

On that May evening I had worked home plate in a Double A game in Orlando between the Savannah Braves, the AA affiliate of the Atlanta Braves, and the Orlando Twins, the AA affiliate of the Minnesota Twins. The Braves won that night behind a young righthanded pitcher named Ricky Mahler (later to play in the big leagues with Atlanta). Afterwards, there was a knock on the umpire’s dressing room door.

My partner got up and opened the door and Henry Aaron stuck his head inside and asked, “Would you guys mind if I asked you a couple of questions?”

I was stunned, of course, recognizing Aaron immediately. Seriously…how many times does Hank Aaron knock on your door and ask to come in.

I was stunned, of course, recognizing Aaron immediately. Seriously…how many times does Hank Aaron knock on your door and ask to come in.

I motioned him in, offered him a half-mutilated folding chair to sit on, and he began by asking my opinion of Ricky Mahler’s performance that night. Aaron, at the time, was serving as the farm director of the Braves organization, and it was his job to assess the progress of their top drafted prospects.

Struck by the irony, I asked, “Why would you ask me, after all the years in baseball that you have? I’m sure you’ve seen a lot of Ricky Mahlers.”

Aaron just smiled and said, “Yes, but not from your perspective. Tell me what you can about his breaking pitches and fastball…compared to the Twins’ pitcher.”

We talked for a moment or so before Aaron thanked me and turned for the door. I stopped him, calling him by his first name.

“Hank, I’d like to ask you a question.” He smiled and turned around.

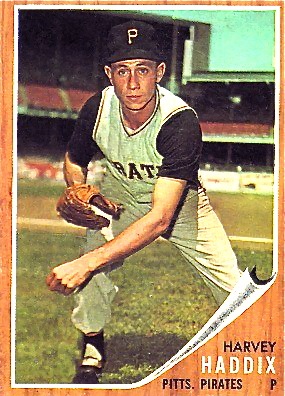

“I live in Ohio, near Springfield…where Harvey Haddix lives,” I said. “And I wondered if you would tell me about the night in 1959 when he pitched the twelve-inning perfect game against the Braves in Milwaukee? I know you were on that Braves team, and scored the winning run in the 13th inning.”

A year later after pitching his 12-inning gem, Springfield native Harvey Haddix was actually the winning pitcher in game 7 of the 1960 World Series, against the Yankees.

I had grown up hearing a lot about Haddix, because my high school coach in Piqua was from Springfield and had caught Haddix during summer baseball games when they played together as teenagers. Hardman used to describe Haddix’s curveball this way: “It looked like an egg falling off a Westinghouse (stove).”

But on that night in Milwaukee – May 26, 1959 – Haddix was 33 years old, pretty much a journeyman pitcher in his first year with the Pittsburgh Pirates, and it was later admitted that the Braves had stolen the Pirates’ signs from their bullpen during the game and relayed the pitches to the dugout and the Braves’ hitters. Still, for twelve innings no one could touch Haddix.

Aaron’s face lit up as he leaned back against the locker room door, then corrected me.

“I didn’t score the winning run,” he admitted. “Felix Mantilla scored the winning run. He had got on base on a throwing error by Don Hoak (the Pirates’ third baseman) to break up the perfect game. Then they walked me intentionally to pitch to Joe Adcock.”

Adcock hit what appeared to be a walk-off home run to deep right-center, but Aaron thought the ball simply bounced off the wall, so he cut across the diamond back to the dugout rather than rounding the bases. Since Adcock had passed him and Aaron had left the base paths, both men were ruled out, and the game ended 1-0 on Mantilla’s run.

“Yeah, I remember that night very well,” Aaron continued. “Funny thing, a lot of us on the Braves bench were actually rooting for Harvey to win that game. Some us knew him because he had been around for a while…with the Phillies and the Reds the two previous years. Harvey was a good pitcher and a nice guy – very popular. And Lew Burdette was pitching for us and some of the guys on the Braves weren’t that fond of Lew.

“Yeah, I remember that night very well,” Aaron continued. “Funny thing, a lot of us on the Braves bench were actually rooting for Harvey to win that game. Some us knew him because he had been around for a while…with the Phillies and the Reds the two previous years. Harvey was a good pitcher and a nice guy – very popular. And Lew Burdette was pitching for us and some of the guys on the Braves weren’t that fond of Lew.

“People have always talked about how good Sandy Koufax’s curveball was, but Harvey threw pretty hard and his curveball was just as good as Koufax’s. I always thought it was a shame that he didn’t win that night, because no one ever came close to doing that again – being perfect for twelve innings.”

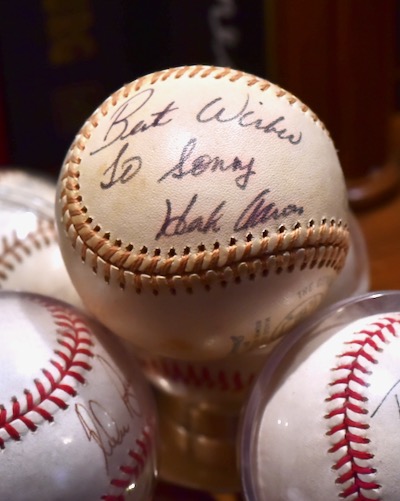

We talked for a few more minutes before he signed a couple of balls and left…and actually thanked me for remembering and asking about that night – May 26, 1959 – the night Harvey Haddix pitched the longest perfect game in major league history.

I still have the baseball that he signed…and that memory of home run king, Henry Aaron.