Time didn’t seem to matter to Tommy Lasorda. It didn’t matter if it had been a day, a week or years since you had last seen him, nothing changed. His greeting was always loud and warm, a verbal embrace that made you feel good about all things.

CINCINNATI – Seems friends are falling left and right these days. Just Friday I heard about Tommy, a fellow who wasn’t too well liked in these parts.

CINCINNATI – Seems friends are falling left and right these days. Just Friday I heard about Tommy, a fellow who wasn’t too well liked in these parts.

Oh, he had a few friends here. But most seemed to think he was a braggart, a blowhard, a bad actor who was more sales pitch than sincerity.

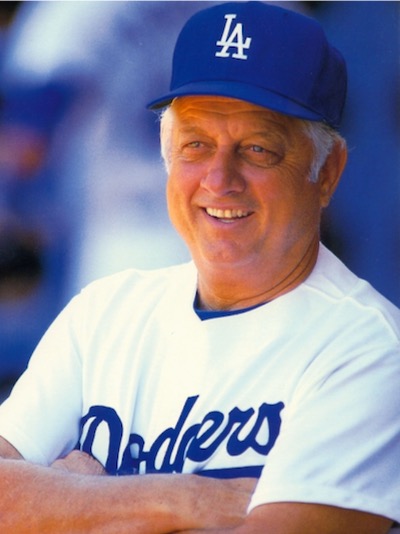

Tommy Lasorda, who managed the Dodgers from 1976 to 1996, died in Los Angeles. He was 93 and been doing battle with a bad heart.

Around here, Lasorda is best remembered as the leader of a dreaded opponent. For so long and for so many it seemed the Reds and Dodgers were engaged in a fight for dominance in the National League. Most years, when LA came to town the rivalry was so intense and important you couldn’t beg or borrow a ticket.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

The rivalry began during Walter Alston’s quiet reign, but when Lasorda took the stage no one sold it bigger, louder or better. Lasorda was one of baseball’s best carnival barkers, right alongside Sparky Anderson. Their love and energy for the game was as boundless as it was infectious. That—along with all their success—is why they stand in the Hall of Fame.

I met Lasorda in 1983 during the National League playoffs. The story has been told before and many times. Hours before Game One I was stumped for a story and I wandered into his office.

There was Lasorda standing on a chair behind his desk. His arms were outstretched and uplifted to the heavens. He looked like an evangelist at a old time camp meeting. Instead of shouting about the wages of sin, he was singing the praises of his ballclub and the glory of Dodger blue. His congregation was small but noteworthy. In one corner stood Leo Durocher, one of the most volatile if not entirely successful managers in the game’s history. Next to him and rapt in Lasorda’s rant was comedian Don Rickles. Chuck Conners, “The Rifleman” of television fame, sat in a chair near Lasorda’s desk. Right behind Conners stood the demur and dainty Florence Henderson, Mrs. Brady of “The Brady Bunch”.

“You never know who will walk into this office,” Lasorda said, pointing at me. “Look, I’ll be damned if it’s not David Brenner.

“You all know David. He’s a great comedian, always on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Great guy. David, come in. Take a seat. Glad you could stop in.”

All around there were nods of acknowledgement and nothing I could do or say, including offering my press pass as proof, would convince Lasorda or his audience I was not the famed performer from Philadelphia, though I must admit there was an uncanny resemblance. From that point forward, I was always “David” to Lasorda.

The following year, I had taken the position as Reds Beat Writer for The Cincinnati Enquirer and was learning the ropes about travel around the league and about each city. On our first trip to LA, I stayed late in the press box finishing a feature. By the time I was done, all the Reds writers were gone. I called for a cab and after an unusually long delay the dispatcher said one would be along. He said, “Meet him in the parking lot.”

The following year, I had taken the position as Reds Beat Writer for The Cincinnati Enquirer and was learning the ropes about travel around the league and about each city. On our first trip to LA, I stayed late in the press box finishing a feature. By the time I was done, all the Reds writers were gone. I called for a cab and after an unusually long delay the dispatcher said one would be along. He said, “Meet him in the parking lot.”

Well, the parking lot at Dodger Stadium is enormous. It’s the size of a small ranch. I packed up and found what I thought was the players’ entrance. To my dismay, however, the parking lot was completely empty except for a couple of cars that looked as though they were parked and abandoned about the time Walter O’Malley bought the property back in ‘57.

A half-hour later, no cab, no traffic and the clock kept ticking. I was beginning to grow very uncomfortable when I spotted car coming my direction. As it began to slow to a stop, I started thinking about how I was going to defend myself. This was not a cab.

The car stopped, a nice car—nothing flamboyant—and the window was lowered. At first, I didn’t recognize the face. “Damn it, David, is that you?”

It was Lasorda with his wife Jo.

“Get the hell in here,” he said. “You wanna get killed. This ain’t Cincinnati.”

He took me back to his office and made a phone call. In a few minutes I was picked up by a car service and headed downtown. When we pulled up in front of The Biltmore hotel, I asked the driver what I owed him.

“Not a thing, man,” he said. “You must know somebody.”

As a rule his Dodgers were a happy lot. Some of that came from winning. Much of it came from Lasorda.

Time didn’t seem to matter to Tommy. It didn’t matter if it had been a day, a week or years since you had last seen him, nothing changed. His greeting was always loud and warm, a verbal embrace that made you feel good about all things. He was a hot-damn, good–to-see-you kind of man, an attitude and bearing that seemed to rub off on all around him, and especially his players. As a rule, his Dodgers were a happy lot. Some of that came from winning. Much of it came from Lasorda.

No one wins two World Championships, four National League pennants and eight division titles because you have talent. It takes a lot more than that and Lasorda had what it took.

When Kirk Gibson played for the Detroit Tigers, he was a somber sort whose pursuit of excellence was dogged and determined. In LA, “Gibbie” found pleasure in the game and a belief that anything was possible even when he was hurt and tired and needed rest more than another game or another at bat.

This was not exclusive to Gibson. Lasorda nurtured his players like a parent, praising them to the extreme at times, and criticizing them, sometimes ruthlessly, when he saw fit. But, most, if not all, loved playing for Lasorda.

Rick Monday played for Kansas City, Oakland and the Cubs before coming to the Dodgers in 1977. He was a smart, seasoned free spirit.

“There is no one like Lasorda,” he once said, “and that’s a damn good thing.”

Tommy’s only trouble was that he was a man of his times. He spoke from his heart. He said what he thought and with little concern for rectitude. In the eyes of some, this attitude hurt him. To others, he was just Tommy, as loveable as he was profane.

It has probably been 10, 15 years since I have seen Lasorda. But I will miss him. He always made me laugh and always made me feel as if I were important to him.

Of course, I’m not sure he ever knew my name. I was always, to the end, David.