Baseball mourns the loss of a legend. My sorrow is for the loss of a man of brilliance, a man of kindness and good humor. My sorrow is for the loss of a friend.

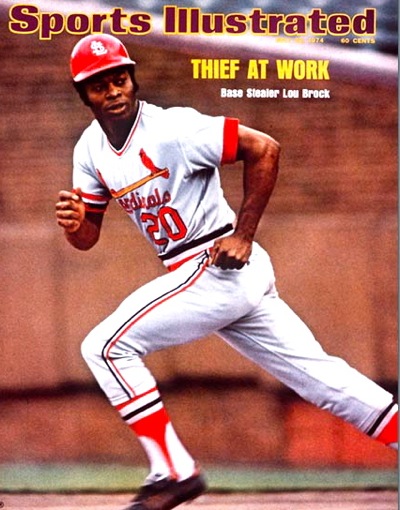

CINCINNATI—Back in the 60’s when I was a kid, Lou Brock was just another face on a baseball card. He became, of course, a Hall of Famer and a St. Louis legend. He was also a friend. He died Sunday after a battle with diabetes and cancer.

When I heard the news my throat tightened and my heart ached, and—honestly—it still does. He helped me in many ways, as I’m sure he did for many others.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

Lou and I became acquainted in the fall of 1980. Brock was in town on a promotion for Anheuser-Busch and since Earl Lawson, our baseball writer at The Cincinnati Post wasn’t available, the sports editor turned to me. “You up for this?” he said.

Up for it? Hell, I almost tore the doors off the building getting to the interview. At the time, Brock was a giant in the game. He had broken Ty Cobb’s record for stolen bases. Cobb’s mark of 892 was believed to be unbreakable, like Babe Ruth’s 714 career homers and Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak. But Brock ended his career after the ’79 season with 938 stolen bases.

I couldn’t wait to meet Brock and he was hardly a disappointment. Brock treated me as though he had known me for decades, like I was some long-lost, shirttail cousin. He was one of the most genuine people I had ever met.

His smile was as broad as the kitchen table. His voice carried a musical note born of his native Louisiana. He made you as comfortable as an old, beat-up, just-right pair of pants. We talked on and on and mostly about what Brock called “the science” behind his record for stolen bases and his approach to the game.

“See,” he said over and over, “you can’t separate one from the other. People think so. They see me or hear about me, and all they think about are the stolen bases.

“Don’t get me wrong. I’m very proud of that, but it’s kind of a product of the way I went about the game.”

There is not enough room her to begin to describe every thing that went into Brock’s success stealing bases. It was mathematical, psychological—physiological. But it was, at bottom, part of an overall approach to the game, and one that altered the Cardinals and led to much of their success in the 60’s and thereafter.

Lou Brock accumulated 3,023 hits, a .293 lifetime average, and 938 stolen bases during his hall of fame career with the Cubs and the Cardinals.

It was best described, perhaps, by Ken Boyer, who anchored the Cardinals infield for many years. Boyer was manager of the Cards in 1981. One morning during spring training we sat in his office drinking coffee by the tanker and talking about Brock’s approach.

“Lou changed the damned game,” Boyer said, “the way people went about the game. Sure, Maury Wills stole bases. (The Dodger shortstop set a single season record in 1962 with 104.) But Lou ran the bases. I mean ran ’em, and all the time no matter the circumstances.

“A perfect example. We’re in Philly, I think, doesn’t matter. Lou gets on. No outs. He’s aggravating the pitcher. Getting a lead, then stretching it. Then, backing off. Driving the guy crazy.”

Finally a pitch is delivered and the hitter pokes one to right field.

“He doesn’t hit it that hard, but Lou had a great jump,” Boyer continues. “I mean he’s half way to second when the ball hits the ground and he is at full speed.”

The guy in right doesn’t field the ball that cleanly and Lou has turned second and is heading full-go for third. The right fielder’s throw is cutoff by the second baseman, who’s looking over his shoulder trying to see where Lou is headed.

“So,” Boyer goes on, “he doesn’t handle the ball cleanly—doesn’t drop it, but doesn’t get a good grip on it—he’s looking for Lou and Lou’s headed home. Hell, he’s bearing down on it.”

So the throw home is off and doesn’t have a lot on it. Boyer is smiling, leaning back in his chair.

“The throw is up the line, third base,” he says. “The catcher has to come up the line to get it. Lou’s out of the baseline a little, just enough to slide around him. Well, he’s safe. Meanwhile, the guy who got the hit is at second and eventually scores on a ground out and a sac fly. We win the game by a couple of runs. Stuff like that happened all the time and the longer Lou played the more it happened.

“Other guys on our club who had some speed started doing stuff like that, not just going one base to the next. It caught on all over the league. Hell, the Dodgers made a livin’ on it, too, and a big, big part—Lou Brock. Take that to the bank.

“We ask Lou about it. You know what he says, he says, ‘Got to make ‘em think. Got to surprise ‘em. Once in a while.’”

Days later, I ask Lou about Boyer’s memories. He only smiled and shrugged. He said he kept notebooks on all his opponents, their strengths and weaknesses; wrote in them after every game and even added things he picked up on opposing players from newspapers and magazines.

The most elaborate notes were on pitchers, their moves to first, their tendencies but no one—nothing—was discounted. His reasoning was simple.

“You need to know. Talent alone,” Brock said, “is never, ever enough. But, knowledge is everything. Knowledge is invaluable and the smallest thing just might help you sometime. You never know. I could never have done what I did without studying other players.”

Once during our travels together he opened the trunk of his car for some reason or another. There was a toolbox, a Brock-O-Bella, a beat up Cardinals cap and heaps of notebooks, all sizes and shapes, spilling out of an old cardboard box. I picked one up. Every line and page was filled. Here were the remnants of a season.

“I got a basement full of those,” he said. “You won’t understand it. It’s my own personal shorthand. That’s knowledge, and you know what they say. Knowledge is everything.”

I have told this story about Lou before, perhaps here. But it seems more appropriate now than ever.

Off and on for the better part of a year Lou and I traveled together working on his project on stealing bases and always he had a small dark book with him. I saw him studying it in hotels, in bars, in restaurants—whenever he had an idle moment.

One night we were working late in his room and I saw it lying on his bedside table. It was tattered and dog-eared “Lou,” I said, “what’s that book you are always carrying around?”

He picked it up, looked at me with that big smile and said, “Why, it’s a dictionary. Haven’t you ever heard the old joke?”

He picked it up, looked at me with that big smile and said, “Why, it’s a dictionary. Haven’t you ever heard the old joke?”

The joke—with minor variations—goes something like this:

A white man dies and arrives at heaven’s gate. St. Peter meets him and says: “Well, hello. We know about you. One last test before you enter heaven. Spell ‘dog’.” The man spells ‘dog’ and St. Peter says, “Come right on in.”

The next man in line is Hispanic. St. Peter says, “Spell ‘house’.” The Asian person spells ‘house’ and goes right in.

“The next man,” Lou says, smiling as broad as can be, “is Black. St. Peter says, ‘Ah, okay. Spell chrysanthemum.’”

“That,” he says, still smiling that smile I will never, ever forget, “is why I carry a dictionary.”

Then, he closed the book, leaned forward, looked at me and said, “Can you spell chrysanthemum?”

When I stumbled and failed, his laughter filled the room. He slapped his knee, joyfully and said: “See, my friend, knowledge!”

Baseball mourns the loss of a legend. My sorrow is for the loss of a man of brilliance, a man of kindness and good humor. My sorrow is for the loss of a friend.