It’s an old story filled with hard truth. It has served me well for years, especially when days were difficult and times were confusing. Lately and for good reason, I’ve played it over and over in my mind. Most of us have such a story. We may not share it but we remember it and hold it close. This one is about shattered glass and a broken dream. It’s about a day when there weren’t enough runs and the outs were all gone. It’s about understanding one’s place in a big damn world that’s not always easy to comprehend.

Hope was slipping away. Wishes were giving way to reality. From the beginning it was a lost cause. That’s all I heard—from everyone.

Hope was slipping away. Wishes were giving way to reality. From the beginning it was a lost cause. That’s all I heard—from everyone.

“Stupid.”

“You’re an idiot.”

My best friend, Sammy Campbell, turned on me: “Do you really believe the Reds can beat the Yankees in the World Series? Come on. Did you hit your head or somethin’?”

My dad, a man who held reason above all else, questioned my logic.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

“Boy,” he said, “you best give this another thought. Those fellas don’t have much of a chance, not much a’tall.”

Deep down I suppose I knew the Reds’ chances were slim-to-none in the 1961 World Series, but I had been lucky enough to go to a few games at Crosley Field, and since then, my loyalties had shifted from the Yankees—who all my friends followed—to the Reds.

But that day—sitting there in front of that small black-and-white Zenith in the old trailer my dad kept at his garage—my heart began to sink. Everything my friends said and my dad had preached appeared to be true, and it looked like I was going to hear it for a long, long time. Looking back I think I dreaded that as much as the Yankees winning the series. (After all, it was real hard to root against Mickey Mantle.)

But here it was unfolding before me: the Reds succumbing to the power and proficiency of the Yankees. It was the ninth inning of the fifth game, New York having already taken three games and riding a 13-5 lead into the bottom of the inning. The Reds were down to their final three outs.

Still, I sat their locked onto the TV set buoyed by the foolish optimism of youth. I was 10 years old. “The Reds could rally,” I tried to convince myself, “climb out of this hole and salvage the series. They had the top of the order coming up.”

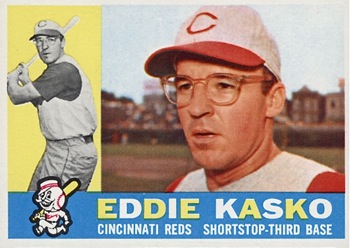

Elio Chacon pinch-hit for Don Blasingame against the lefty Bud Daley, but he grounded out to short. The next hitter was Eddie Kasko, who next to Frank Robinson and Wally Post, had hit better than anyone among the Reds in the series.

About that time my dad walked into the trailer and stood behind me. He needed to go to town to buy parts for a job he was working on and wanted me to hurry along.

Shortstop Eddie Kasko, who died recently, was one of my favorites, and played well against the Yankees in ’61.

“This is over, son, come on,” he said. “They haven’t done anything since the fifth, and they’re not going to. Let’s go. We’ll get something to eat, a burger or something.”

“I’m coming, Dad,” I said. “Just a minute.”

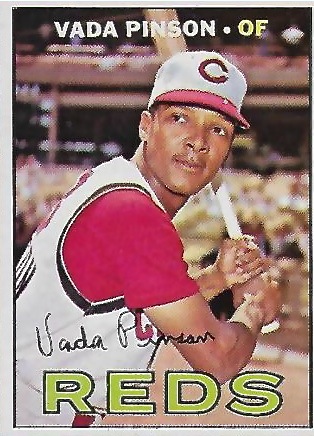

Kasko hit a harmless fly ball to right. There were two outs and the Reds did seem dispirited, resigned to their fate. But, the next hitter was Vada Pinson. Pinson was my favorite, a top-notch hitter, a player with style and good looks, and nobody—other than Willie Mays—played a better center field. Maybe he could get a hit, get Frank Robinson to the plate, get something going. I was hanging on; Dad wasn’t.

He was out at the car. I could hear him yelling for me to hurry up. His patience were growing thin. He honked the horn on the big, blue Olds.

“Damn it, son, come on.”

Vada Pinson popped up for the final out in the ’61 Series.

Vada popped up just beyond third base. It was a weak fly ball. It was over. The Yanks celebrated in the midst of Crosley Field. The Reds stood watching for a bit then headed for the tunnel that led to the clubhouse, heads down, faces blank.

I sat listening to the announcers prattle on and then, again, I heard dad’s car horn. I was angry. I was angry with the Reds, angry with my father and with the prospect of listening to my friends brag and boast and needle me for days to come.

I got up and walked out of the trailer, slamming the door as hard as I could. The next sound was shattering glass. I had slammed the door so hard the window had broken.

The next sound I heard after the last shard of glass came to rest on the stone steps was my father’s voice.

He spoke in a slow, measured, quiet tone. “What in the hell was that about?” he said.

I couldn’t answer, couldn’t speak. My anger was displaced by fear. My dad had never hit me, but I thought the first strike might be coming. It wasn’t.

“Talk to me,” he said. “Tell me why the hell you just broke a window—that you will pay for. What was the reason? What was the purpose? Don’t tell me it was because of that baseball game.”

I nodded, my eyes on the ground, my head down. “I wanted them to win,” I said.

“I see that you did,” he said, looking over at the broken glass. Suddenly, he was no longer in a hurry to get to town. He told me to take a seat on the bench there in front of the trailer. Then, he sat down beside me. I had no idea what was coming.

“First of all,” he said, “I want you to look at me. Okay, good. Now, let me see if I’ve got this straight. You’re mad because the Reds lost the World Series, right? So mad you slammed the door and broke the window. And, that makes good sense to you?”

“Well, yes,” I said.

St Henry’s Wally Post homered in the final game, but it was too much, and too late for the Reds.

He stroked his chin and looked off like he was trying to figure out just exactly what he wanted to say.

“Okay, let me ask you a question or two. Did you get a single at-bat in the series? No, you didn’t, did ya.

“Did you catch a ground ball or a fly ball? Did you miss one? Did you throw a strike or walk a batter. Did you strike out or get a hit?”

To each question, I said, “No,” and each time he said, “I didn’t think so.”

He said nothing for a long while then, he nudged me on the shoulder with his fist.

“So let’s think this through. There is nothing you did or could have done that would have changed the outcome or had anything to do with it. But you were so mad you broke a damned window and you are bound to pay for it. That window is gonna cost about ten bucks, and on a fifty-cent a week allowance it’s gonna take a while.

“Now, look at me, son,” he said. “Do you think that’s smart? Losing your temper like that over that game? And let me go you one better. Do you think any of those boys who play for the Reds, do you think any of ’em care that you broke a window because of them losin’ and you got to pay for it? Don’t think so. Not for a minute.”

He stood then and stuck both hands down in his pockets.

“Here’s my advice, boy. The next time you get that ticked-off about a baseball game, it better damned well be one you played in. There’s no sense in getting that mad and all worked up over things you can’t control or don’t have a hand in. You understand?

“Besides, anger and worry are thieves. You let ‘em, they’ll take your health and steal youth. You’ll wake up one day and be a bitter, wrinkled-up, beat-up old man, and I don’t think you would want that and I wouldn’t want it for you.

“Now, go on and get a broom and a bucket or somethin’ and clean up your mess so we can go to town, okay.”

That was nearly 60 years ago, but it was a lesson well learned, and I’ve lived by it since that day back in Blocher, Indiana—October 9th, 1961.

Over the years, there have been lots of things that have stirred me to anger. But I’ve always tried to think of Dad, smarter than most, always with a cool hand and a cool heart.

There have been good days and bad ones, but I’m proud to say I haven’t broken a window since Vada Pinson hit that lazy fly ball to left—that last out at Crosley—when the Reds fell to a better team.

Bats for every occasion, including ‘fungos’. Phoenix is proud to support Buckeye baseball on Press Pros.

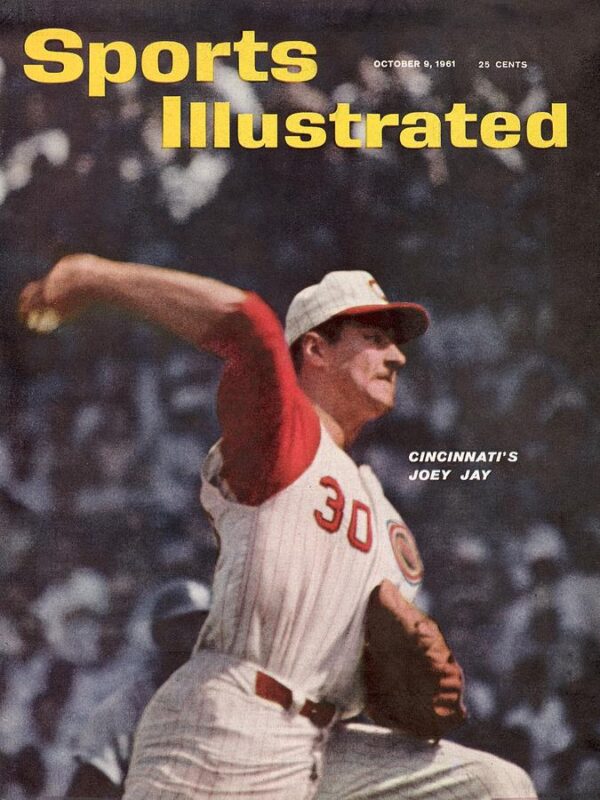

Joey Jay was a Reds All-Star in '61, and pitched brilliantly in Game 2, but didn't have it in game five against the Yankees. (Press Pros File Photos)