Deion Sanders was the rage in the late ’80s when he became the second multi-sport professional athlete in a decade after Bo Jackson, but he was not appreciated in Columbus.

Columbus – His eminence stared straight ahead inside the cockpit of a spanking new jet-black Mercedes-Benz coupe with fire engine red interior. He pretended to be driving through hairpin turns.

Columbus – His eminence stared straight ahead inside the cockpit of a spanking new jet-black Mercedes-Benz coupe with fire engine red interior. He pretended to be driving through hairpin turns.

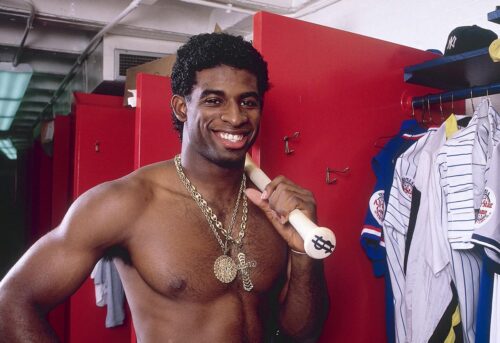

The vehicle was in park and sitting on some grass outside the clubhouse at the New York Yankees minor league spring training site in Tampa. It was March 1989 and the subject of our story wore Oakley sunglasses – the pricey rage in baseball at that time – diamond earrings that looked to be nearly the size of a pinky fingernail, and a gold chain that might have been able to tow a small car.

This reporter needed to write interesting stories about present and possible future Columbus Clippers, and Deion Sanders was a great candidate simply because he was Deion Sanders. He had just completed his run as an All-American Florida State cornerback and kick returner.

Veteran columnist Mark Znidar writes the Buckeyes for Press Pros Magazine.com.

The Yankees were infatuated with the guy and drafted him in the 30th round the year before knowing full well that he was going to be a sure-fire top 10 pick in the upcoming NFL draft.

Sanders was determined that he could become the next Bo Jackson by playing football and baseball at a high level.

New York front office types treated him as if he was going to be the next big thing in pinstripes. That was in an era when owner George Steinbrenner routinely called out players on the back page of the tabloids in his warped way of trying to put a bonfire underneath their butts or run them out of town.

Steinbrenner coveted big names beginning with Reggie Jackson and continuing with Dave Winfield and Roger Clemens, among so many others. The guy even made former Michigan quarterback Drew Henson a multi-millionaire, and he couldn’t play third base a lick.

Gotham City loved Sanders, and he loved it back because anything he said or did were headlines in The Post and Daily News.

On this morning, though, Sanders not once looked at me in the eyes. He kept pretending to steer his car and spat out one-sentence answers hoping to shoo me away so he could get on with his life.

Early that season, the Yankees moved him from double-A Albany to Columbus. He would lead off and play center field.

Of course, the office wanted a story about Sanders as soon as possible. One New York writer called and asked that I tell him what Sanders was wearing to the ballpark and to supply a blow-by-blow account.

I approached Sanders before batting practice as to not interfere with his pregame routine. I stood at his cubicle and asked if it was the right time to talk.

“I’m not talking to you,’’ he said.

Was it the story I wrote in spring training? It was a blah piece because the interview went so badly.

“I don’t talk to minor league media and you are minor league,’’ he said.

So he was never going to talk to me? The Dispatch had me staff all Clippers games, and that was 144 not including playoffs.

“Nope,’’ he said.

But there was plenty to write about even if he didn’t say a word.

“I’m not talking to you,” said Sanders. “I don’t talk to minor league media, and you are minor league.”

Manager Bucky Dent, a saint of a man, was forced to fine Sanders time and again for not running out balls, for missing signs and for being late to pregame.

When he became frustrated with New York’s penchant for calling him up for a handful of games and then sending him down, Sanders sort of went public with it. On a chilly night in the mountains of Wilkes-Barres, Pennsylvania, the top layer of the artificial turf actually froze. So Sanders scratched out “Yankees Suck’’ with his spikes in center field.

Shortly after came my big confrontation with him. The Yankees shipped him back down again after he batted something like .132. The headline was that New York Newsday quoted Sanders saying that Columbus was a cow town and that the fans didn’t know anything about baseball.

The editor gave me a printout of the story and told me to hand it to Sanders so he could refute or back up what he said.

When he came off the field after infield, I asked whether he had read the story and if he was quoted correctly. The Dispatch was going to print the story if he had no gripes about how it was written.

“Yes, it’s true,’’ he said.

I asked him if he would talk about some points in the story.

“I’m still not talking to you because you are minor league,’’ he said.

I said that makes two of us. Remember that the Atlanta Falcons had just made him the fifth player taken in the draft as a cover corner.

“Why do you say that?’’ he said.

“Well, no one – absolutely no one – can call himself a major leaguer if he bats .132,’’ I said.

Sanders went ballistic and had to be held back by several teammates in the dugout. He was shouting almost as if talking in tongues. I could not understand a word, but stood my ground.

I told him it would be worth at least a 10 grand settlement in injury compensation in court if he hit me, and that my family would appreciate a portion of his signing bonus.

Reporters should never say that, but what was there to lose? He wasn’t talking to me and I was not going to take it anymore. No way was I going to look like a lamb in front of other players and get the reputation of being wimpy. It was a testosterone versus testosterone moment that I was not going to lose.

Dent and his coaches, by the way, got a kick out of my little show.

Minutes went by and a number of players came running out of the clubhouse and into the dugout to ask me what had happened. One player said Sanders was throwing things in the clubhouse and cursing.

Things quickly went back to normal, with Sanders ignoring me and me writing about everything he did, good and bad. Teammates loved him. He bought them dinner, shared his taxis and mingled with them. Coaches put up with him.

Sanders would stand on the top step of the dugout and give the fans what they wanted, and that was attention in exchanging trash talk.

The highlight of his tenure with the Clippers came during a two-day span, starting in Richmond, Virginia. One night, fans behind the third base dugout were giving Sanders and his soon-to-be-wife a hard time.

Sanders would stand on the top step of the dugout and give the fans what they wanted, and that was attention in exchanging the trash talk.

The woman, whom Sanders called “my female’’ rather than her first name, got so upset that she held up a hand-made sign that read, “You are jealous because he is going to be rich.’’

The game was a rout for the R-Braves and Dent took Sanders out of the lineup in the seventh or eighth inning.

Immediately after the final out, I waded through spectators trying to get to the clubhouse. Sanders walked down the concourse from the other direction sporting a smile you see after home runs.

My interview with Dent was just beginning when two policemen walked into his office. I can’t describe the look on his face. It was bewilderment and then fright.

“Is there something wrong?’’ Dent asked.

Before the police could answer, I said, “It has to be Sanders.’’

One cop said, “That’s right. That’s the guy.’’

Dent asked me to leave, but my work was just beginning. The game became a footnote. Players stopped me to ask what had happened. It was a long day, and thank goodness it was a day game. There were calls to the police station, the Clippers front office and office to give updates.

What Sanders did was change into his street clothes during the game. When the game ended, he went into the stands and attacked a heckler by grabbing an arm and giving it a good twist. He threw in a few punches for good measure.

Police arrested Sanders at the team hotel. The next morning he was standing in front of a judge. Dent stayed with him as a nurse maid while the team flew to Columbus. He never received a word of thanks for his efforts.

Part of Sanders’ deal to avoid jail time for assault and battery was writing a sizable check so the R-Braves could build a handicapped section at The Diamond.

There was never better theater in the minor leagues than the next game at Cooper Stadium. A large crowd on a giveaway night was in attendance, and one of those faces belonged to Steinbrenner.

What did Sanders do with all eyes on him? He did what he usually did when his butt was on the line. He made a great running catch, stole a couple of bases and hit a walk-off shot off the top of the wall in right field. He had three hits in all.

The New York media dubbed him “Neon Deion’’ for enjoying the spotlight. He hated that. His self-invented name, which he spread like a publicist, was “Prime Time.’’

Given that he was a part-time big leaguer, Sanders did okay for himself playing for the Yankees, Braves, Reds and Giants batting .263, getting 558 hits and stealing 186 bases playing through 2001.

These days in the home run derby era, there would be little excitement about Sanders. His game was hitting singles and stealing bases with legs so spindly that they looked like they belonged to a marathoner. His career on-base percentage was .329 and his slugging percentage .392.

No one, though, could quibble with his guts in big games. In 1992, He went 8-for-15 to hit .533 and stole five bases for Atlanta in a World Series loss to Toronto.

I continued to be a minor league baseball writer until 1994 and Sanders began putting together a Hall of Fame career in pro football. He was on a Super Bowl champion with Dallas in 1995. He was in eight Pro Bowls and voted first-team All-Pro six times.

Why only 53 career interceptions? That’s easy. Like Herb Adderley, Thomas Lott and Richard Sherman in their best seasons, no one dared throw in Sanders’ direction. He took away his side of the field.

Alas, I was not done with Sanders. In 1995, the Reds beat writer for The Dispatch took a series off. I groaned as soon as the sports editor gave me the credential and parking pass.

I took a deep breath when I walked through the double doors of the Reds clubhouse at old Riverfront Stadium knowing there was good probability that something strange might happen. No other media was around. Talk about a canary in a mine.

Sanders’ eyes and mine met at the same time.

“Oh, no,’’ he shouted. “Not you again.’’

Kevin Mitchell, all 250 pounds plus of him, asked Sanders what was the matter.

“That’s the guy who dogged me in the minors,’’ he said.

Now, any reporter drawing the ire of a player for something he or she wrote draws the ire of everyone on the roster. Back then, they could make your job miserable or even shut you out.

“Why did you do that to my man D?’’ Mitchell said.

I explained to Mitchell that Sanders had been fined and disciplined by the Clippers all the time and that he even was arrested.

I made sure to approach Mitchell to let him know I was standing my ground and that what I was saying was the truth. It was my job to write about those things, I told him.

At that, Sanders waved me over.

“Let’s talk,’’ he said.

And we did talk for a few minutes.

I told him that we could have made for a great pair. I would have written down his every word because people wouldn’t be able to get enough of him. I told him I surely would have told the New York media about his every move.

“It could have been a lot of fun for both of us,’’ I said.

We actually shook hands.

And that was that.

In 45 years in the business, only Dale Earnhardt was as magical as Sanders in person.

I have angered players and coaches, but the heat never lasted long.

Boston manager Don Zimmer once tore me to shreds on Opening Day in Cleveland for asking whether 30-degree weather hurt the Red Sox being two-hit by journeyman Rick Waits. Translation: Kid, it was the same conditions for both teams.

You take the good with the bad in the writing business. Interviews can be risky.

Ohio State basketball coach Gary Williams once threw a phone against the wall in his office after I made a pretty careless mistake in print. An assistant told me about the wall part because I was on the other end of the line. Translation: Be careful, you idiot.

Bengals receiver Carl Pickens, who had anger problems like Albert Bell, once pointed a water pistol at me and said he wished it was real. Translation: Don’t ask me if a wicked combination of sunshine and shade in the end zone caused me to drop a pass in the fourth quarter against the Giants in The Meadowlands. I’m a pro.

It’s just too bad that I caught Sanders at a time when he was full of himself.

Years later, Sanders revealed that in a national story that he once considered taking his life. He was that depressed despite all that fame and money. There was a pretty bad car crash that he walked away from. He got divorced.

Now, he’s an established analyst for CBS and the NFL Network. He started a private school in Florida.

Bravo for him.