Athletic director and administration have talked about allowing as few as 20,000 to 22,000 people in Ohio Stadium for football games in order to follow social distancing guidelines. The hope is not to play in front of empty seats.

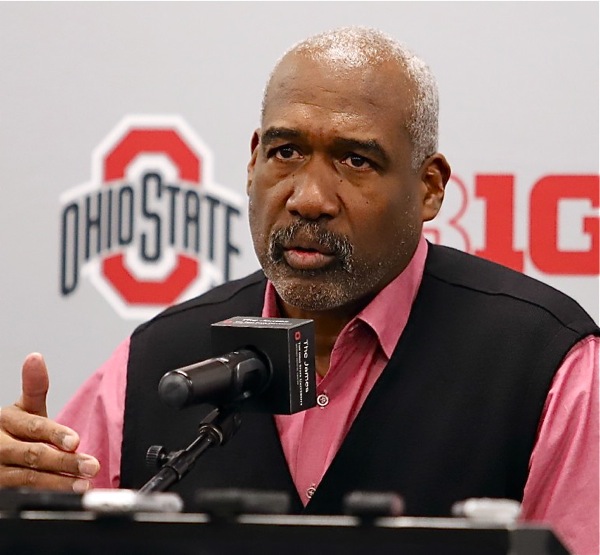

Columbus – The problem Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith and the ticket office usually have is telling people why they were shut out of getting season football tickets or where the seats are located.

Columbus – The problem Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith and the ticket office usually have is telling people why they were shut out of getting season football tickets or where the seats are located.

On game days from his luxury box high atop the stadium, there isn’t a better feeling for him than seeing more than 100,000 spectators watching the game and drinking, eating and buying souvenirs in mass quantities at Ohio Stadium.

How things have changed in the wake of COVID-19.

Smith discussed the very real possibility of the Buckeyes playing at least some games this season in front of only game personnel, radio and television announcers and media to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

“I still struggle with that concept,’’ he said Wednesday during a teleconference. “However, I could get there if that is ultimately what we do.’’

The optimist inside Smith says to expect at least some fans to enjoy the game experience and hopefully all 12 games. Ohio State ranked third nationally in average attendance last season with an average of 103,384, or a little more than 1,000 less than the 104,944 capacity.

Of course, nothing can happen until Ohio Department of Health director Dr. Amy Acton and Governor Mike DeWine say it can. Smith is like every other business leader in keeping his ears open.

Smith has been living on Big Ten and NCAA teleconferences in getting the latest information, hearing opinions, going over potential models for fall sports and being asked about his take on the situation.

How can the university make it safe for spectators and game workers with so many people inside the stadium?

The short answer is Ohio State can’t at the moment.

The athletic department, though, has talked about allowing a much smaller number of spectators. As few as 20,000 to 22,000 people might see games live and family, friends and relatives would be among the first in line.

The athletic department has a point system in place for ticket allocation and will use that if capacity is drastically reduced.

“We’d have to make sure that we look at each individual group — faculty, staff, students, donors, Varsity O, parents of athletes, all those different constituencies — and come up with some strategies within those groups,” he said.

There also is the possibility that some universities might not be open when the season begins. The Buckeyes open against Bowling Green on September 5 at home.

Mid-major colleges have begun shedding varsity sports in an attempt to cut their losses. Bowling Green really needs to play against Ohio State because of the seven-figure game guarantee. That university has discontinued baseball to cut costs.

Game 2 is scheduled against Oregon on September 12 in Eugene, Oregon, for the beginning of a two-year home-and-home contract. Smith took a firm stand when asked whether the Ducks could play in Columbus if their state is still closed because of the virus.

“We’ll just play both of them here two years in a row,” Smith said in jest. “I’m not sure I would flip (the games) because we wouldn’t have seven home games next year, just off the cuff.”

There have been discussions about football teams playing only conference games. The Buckeyes are scheduled to open Big Ten play against Rutgers on September 26 at home.

There have been discussions about football teams playing only conference games. The Buckeyes are scheduled to open Big Ten play against Rutgers on September 26 at home.

Conference people, Smith said, haven’t talked about playing with fewer than 14 teams.

Smith said Ohio State officials have not set policy about what would happen if a player or players tested positive for the coronavirus.

“We’re really turning that over to the medical experts,’’ he said.

The key words Smith kept using were patience and discussion before anything is decided.

“The perfect scenario is that we have a national solution where there is some consistency,” he said. “For example, do we just play conference games? And then what is that number? You would hope that there is a national consistency in that and that it ties into your post-season in some form or fashion and the selection criteria for post-season changes and accommodates that national solution. That is the best scenario.

“The perfect scenario is that we have a national solution where there is some consistency,” he said. “For example, do we just play conference games? And then what is that number? You would hope that there is a national consistency in that and that it ties into your post-season in some form or fashion and the selection criteria for post-season changes and accommodates that national solution. That is the best scenario.

“I think we need to not rush this. I know everyone is anxious to do that, but we need to have the opportunity for our medical experts to continue to collect data, see our human behavior responds in the reopening environment across the country.’’

Smith did stress that hard decisions need to be made by early July for “clarity” because football teams, for instance, ideally need six weeks of training camp to prepare.

And, again, he stressed that more discussion and information will lead to a picture that is clearer.

“I think as we get closer to what reality might be, we’ll get more focused on what we have to do there,’’ Smith said. “Our kids want to play. But if we can’t put the kids in a position to play in a safe way, then all the other questions are moot.’’

“I still struggle with that concept,’’ said Smith, of playing before empty seats. “However, I could get there if that is ultimately what we do.’’ (Press Pros File Photos)