Cincinnati – This past week another from the high time of Major League Baseball passed away. We lost Hall of Famer Al Kaline, who, unfortunately, spent his career playing in the long shadows of legends like Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays.

Kaline was a 10-time Gold Glove outfielder and a marvelous hitter who played 22 seasons for the Detroit Tigers. On a Saturday afternoon when I was just a boy, Kaline made an impression on me that never faded. What occurred that day was plenty enough, but fate sealed the deal years later in Lakeland, Florida.

It was fate that brought us together at a picnic table at Joker Marchant Stadium. That afternoon was one of the best of my professional life and it led to one of my favorite stories I’ve written for Sonny Fulks and Press Pros Magazine.

It first appeared on June 6, 2013. My hope, of course, is that I was able to convey what a good and gracious man Al Kaline truly was. My wish is that any and all with a love of baseball could have had the good fortune to meet the man. My further wish is that I had one more afternoon to spend with him, as I’m certain so many others do. (Greg Hoard, April 11, 2020)

It first appeared on June 6, 2013. My hope, of course, is that I was able to convey what a good and gracious man Al Kaline truly was. My wish is that any and all with a love of baseball could have had the good fortune to meet the man. My further wish is that I had one more afternoon to spend with him, as I’m certain so many others do. (Greg Hoard, April 11, 2020)

June 6, 2013 – We were a dusty lot: Sammy, Shep and me, all crowded around the black and white television set, each elbowing for the best possible position.

We had spent the morning on a scrubbed out diamond up town playing ball, learning baseball, playing baseball, fielding ground balls on rough ground, learning to take one in the face, still managing to make a good throw, finding out how to catch a ball glancing off the limb of a maple tree or rolling down off Ruth Trotter’s garage.

Baseball was everything to us, and this was our holiday. This was Saturday afternoon, time for The Game of The Week: Dizzy Dean smiling and singing “The Wabash Cannonball,” Pee Wee Reese, there at his side, telling us stories about Mantle and Mays and Roger Maris, who just last season hit 61 home runs, accomplishing the unthinkable – breaking Babe Ruth’s single season home run record.

“He’ll never do it again,” Shep said.

“He’ll never do it again,” Shep said.

“Betcha,” said Sammy, the most avid Yankee fan among us.

“Okay,” Shep countered, “a dollar.”

“You ain’t got no dollar.”

“Do so! C’mon, bet. Shake on it.”

“Shut up! They’re about to start,” I said.

“Yeah,” Sammy said. “Shut up, Shep. Still ain’t got no dollar. Ain’t never had no dollar.”

That Saturday the Yankees were playing the Detroit Tigers at Yankee Stadium and Pee Wee said that while New York was again the favorite to win the pennant, Detroit could pose some problems for them.

We loved Pee Wee, trusted him. He was from just down the road, Louisville, Kentucky. He talked like us, sounded like the people we knew. He told us about the Tigers, explained why they could challenge the Yankees. They had Norm Cash, who hit for average and power. They had Rocky Colavito, who had come over from Cleveland, and, of course, he said, there was Al Kaline. “And we all know about Al Kaline,” Pee Wee said.

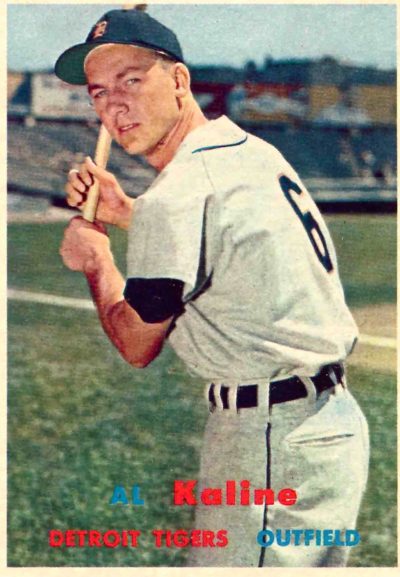

Kaline as he appeared on the vintage 1957 Topps trading card.

“We surely do,” said Dizzy, that grin, that chuckle always present in his voice. “You betcha, one of the best in the game.”

That day we learned about Kaline.

Bottom of the ninth, the Tigers led 2-1. Elston Howard was at the plate. There were two outs and a man on second. Howard sliced an outside pitch to shallow right field. Sammy started yelling, “Tie game! Tie game!” But here came Kaline, running fast, bending low and then lower. He reached down, his glove just grazing the outfield grass. He made the catch. He went to the ground, rolled on his left shoulder. The game was over and Kaline was hurt. His collarbone was broken, but it was one helluva play. Tigers win. Yankees lose.

Sammy bitched.

“I like this Kaline,” Shep said.

“Yeah,” I said. “He could have pulled up, played it on a bounce. Didn’t. He went for it.”

“Screw Kaline,” Sammy said.

Pee Wee and Dizzy praised Kaline; told us that’s the way he always played the game.

That evening we went back to our scrubbed out field, gathered every kid who could play the game and had another. As always, we assumed the names of idols. Sammy took his position at short and said, “I’m Kubek.”

Shep went to first and said, “I’m Musial.”

I trotted to the outfield. Always I was Mays. That day it was different. “I’m Kaline,” I said.

On that day, May 26, 1962, Kaline was hitting .345 with 13 homers and 38 RBI’s. The injury cost him two months of the season. Still, he ended up hitting .304, driving in 94 runs and hitting 29 home runs.

Schwieterman Custom Body Shop is pleased to support youth baseball on Press Pros.

Had he been healthy, the Tigers might have, as Pee Wee suggested, made a run at the Yankees. Norm Cash hit 39 homers and drove in 89 runs. Colavito hit 37 homers and drove in 112 runs. Jim Bunning won 19 games. Hank Aguirre won 16. Don Mossi and Phil Regan each won 11. Still, the Tigers finished fourth in the American League, just nine games over .500.

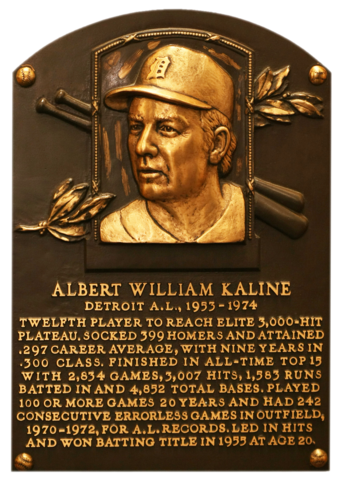

But, because of that catch, I ended up making a study of Kaline. He came into the league in 1953, an 18-year-old bonus baby. Two years later he won the batting title. He hit .340. He was 20 years old, and finished second to Yogi Berra in the MVP voting. He wasn’t a power hitter. He wasn’t glamorous like Mantle and Mays. He was, well, normal, but solid, dependable, patient comes to mind. I liked the way he carried himself in the field and at the plate; liked the way he wore the uniform.

For years, I carried his ball card around in my wallet, right there along side my driver’s license, draft card and student ID, and well after Kaline retired in 1974, even after he was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1980.

From time to time, people would see the card in my wallet and ask about it, usually something like, “You a Tigers fan?”

“Nope,” I’d answer, “just always appreciated Al Kaline. Ya know, from 1953 through 1965, he never struck out more than 57 times in a season. Do you know how impressive that is? Over 500 at bats a season and ya strike out less than 10 percent of the time?”

“Baseball guy, are ya?”

I was then; still am.

In 1985, I was covering a spring training game in Lakeland, Florida, the Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers, at Joker Marchant Stadium. The Tigers were defending world champs. The Reds were trying to find their way under the managerial tutelage of Reds legend Pete Rose, who was, in retrospect, more engaged in securing the all-time hits record than leading his team back to respectability.

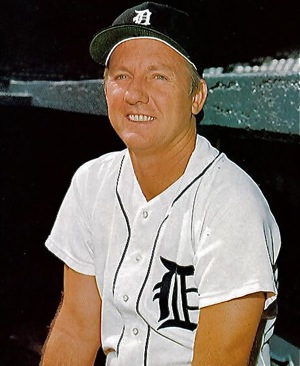

It was a glorious March day, high blue skies. So, I grabbed my scorebook and fled the press box. I found a picnic table down the right field line just beyond the bleachers. It was a perfect vantage point, solitary, peaceful just the sounds of the game and crowd riding along on a soft breeze. About the second or third inning, an older man came riding up in a golf cart. His hair was snow white. He was trim and fit. He wore Tiger uniform pants and a blue sweatshirt. He was tanned, dignified.

“Great spot,” he said. “Mind if I join you?” He had a Coke in a large plastic cup and a chicken sandwich half-wrapped in foil. “You with the Reds?”

Kaline played 22 seasons with the Tigers and finished with a career average of .297, 3,007 hits, and 399 home runs.

I said I covered the Reds for The Cincinnati Enquirer. He smiled. “Next best thing to playing the game is covering the game,” he said. “My name’s Kaline. Al Kaline.”

To that point, neither of us had turned our eyes from the field. “Al Kaline?” I said.

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m honored,” I said, extending my hand in greeting. He wiped his hand on his pants, rubbing away a gob of mayonnaise. “Pardon me,” he said. “This is one sloppy sandwich. I shouldn’t be eating it, but it’s awful good.”

The rest of the afternoon, we talked baseball, ambling along, one topic after another. Would the Tigers repeat? “Don’t know,” he said. “It’s hard to do what they did last year. Everything just fell into place. Just got to play ’em out; see what happens.”

He asked about the Reds. “It’ll all come down to pitching,” I said. As soon as the words were out of my mouth, I realized how stupid and cliché they must have sounded.

“Probably,” he said, with just a hint of a smile. “Generally does. Ya got to figure Pete will spark ’em and (Dave) Parker is still a bona fide all-star. I like that Soto, Mario. Great change. Beyond him, doesn’t seem to be much there.”

Honestly, I don’t remember much about the game that day. I believe the Tigers throttled the Reds, Kirk Gibson and the rest of the Tigers lighting-up every pitcher who wandered in from the visitor’s bullpen.

All I remember is sitting there talking with Al Kaline. Along about the fifth inning or so, I told him about watching his catch on May 26, 1962, and how I had walked around with his ball card in my wallet for years after that.

He smiled. “Yeah, that catch cost me some time. Don’t know that I was ever the same after that. So, you carried my card around in your wallet?” He seemed genuinely impressed. “Ya still got it?”

“Unfortunately, I don’t,” I said. “Some years ago I lost that wallet. I think I left it in a bar. Maybe Chicago.”

Kaline laughed. “Lot’s been lost in Chicago,” he said.

Kaline laughed. “Lot’s been lost in Chicago,” he said.

“Lost everything: driver’s license, credit cards, all of it, even your card – a 1957 Topps.”

“That’s a shame,” he said, “I mean about your credit cards and such. Always a pain taking care of that stuff.”

“Yeah,” I said. I couldn’t help but laugh and so did he.

The game had reached that point every spring game reaches, when both teams are running out every retread, rag-tag hopeful and promising minor leaguer in the organization.

“Well,” Kaline said, stretching, “’bout time for me to get a shower and get on outta here. This here, this doesn’t mean much. They’re just taking a peek, resting the regulars. Nice meeting ya. Nice talking with ya.”

“My pleasure, Mr. Kaline,” I said.

“It’s Al,” he said. “Call me Al.”

Later that summer, I went to a card shop and bought another Kaline card. It’s the one you see here from 1959. I don’t carry it in my wallet. I keep it in a safe spot, just like the memories.

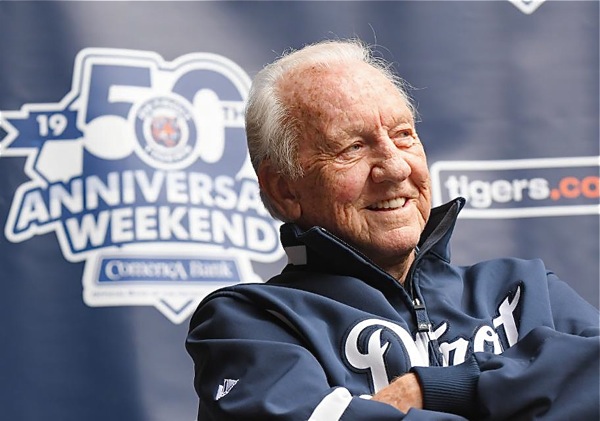

How Good Was Al Kaline?...Modern baseball fans have forgotten and overlooked the Tigers' Hall Of Famer who signed when he was 18 years old, never played a day in the minor leagues, and finished his career with 3,000 hits. (Photo Courtesy Of The Detroit Tigers)