If you have the patience to read and consider…enjoy the words and perspective of columnist Greg Hoard and his reflections on other times, other people, and the obstacles that helped another – greater – generation of people survive hardship, and come through it, “just fine.”

Cincinnati – The call came too early to be good news. The voice on the line was hesitant at first. “Uh, sir, there is no emergency. Your mother is fine.”

Cincinnati – The call came too early to be good news. The voice on the line was hesitant at first. “Uh, sir, there is no emergency. Your mother is fine.”

She was clearly young, an aide at the facility where my mom has resided for the past few years.

“I’m just calling to inform you that we will not be permitting visitors until we receive further word regarding the virus.”

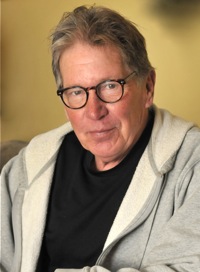

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Cincinnati Reds for the Cincinnati Post…and sports anchor for Channel 19, WXIX.

The virus…Covid 19

She was probably reading from a printout, trying, at once, to allay the fears, the anger she expected to encounter.

I thanked her for the call, told her I had expected something of that nature and ask her to keep me apprised. As we spoke, I thought of my mom, now 92 years old and still tough as a knot.

I should qualify the last. She’s still mentally tough. She doesn’t walk and will not leave her bed. Ask her how she feels and she will laugh just a little, then turn those honey brown eyes on you with a look that says: “Now just how do you think I’m feeling?”

She doesn’t say that, of course. She’s too nice, tries to be, any way; always has even in the worst of circumstances.

I remember a night when the snows were blowing and money was very short, much of it spent to make sure there was food on the table and the animals were fed. I was nine, maybe 10. It was cold that creeps through windows and crawls under doors.

We were short of fuel for the stove and while the wood stove was stocked and burning, the chill invaded the big, high-ceilinged rooms of the old farmhouse.

We had driven up the road and bought five gallons of fuel oil. It was all we could afford. Back home, we hauled it out of the trunk of the ’56 Buick and, together, carried it from the driveway a few hundred feet to the big oil drum at the side of the house.

There was a stepladder there and she climbed up to unscrew the top of the drum. I did my best to hoist the can up to her and, somehow, she managed to dump the oil into the drum, spilling some down the side, dropping a flashlight and cursing her error and the night. I couldn’t help but laugh; Mom cussing.

The job still wasn’t done. She sent me to the woodshed for bricks and when I returned with a stack of two or three, we tipped the drum up and propped the bricks beneath one end so the oil would run down high above the spicket.

“There,” she said, a scarf wrapped closely around her neck, an old, knit hat pulled down on her head. “That should get us through the next couple days. We will be fine.”

There in the dark, in the cold and wind, I could see those eyes and hear her words.

“There, we will be fine…”

That night, I went to bed under homemade quilts listening to the fire crackle in the stove and watching its light dance throughout the room, across the walls and windows.

That night, I went to bed under homemade quilts listening to the fire crackle in the stove and watching its light dance throughout the room, across the walls and windows.

She said there would be bad times. She said we would be fine…

The polio scare came along about then. It shocked and scared the country. The disease withered and destroyed limbs. It struck children. It affected friends.

I remember standing in line outside the local high school waiting to get the vaccine that prevented the illness. People said there might not be enough to go around. Some time later we learned that a classmate would miss all of the school year because of polio. He missed more than a year, but, in time, he was well. We played baseball and basketball together in junior high and high school.

When times were tough, Mom said there had always been times that were worse. She was right.

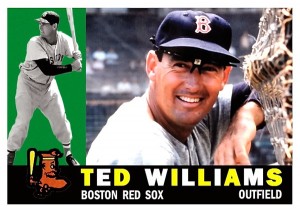

My dad fought in World War II. He came home with five major battle stars. He didn’t get a scratch. His scars were inside. He wouldn’t talk about the war, wouldn’t talk about much other than baseball and how Ted Williams was the grandest hitter “the world had ever seen.”

Finally, one night when there were lots of beer bottles on the table and he was making one of his rare visits, I hounded him about his days in Europe.

He finally looked at me and said, “I was cold and wet and dirty for almost three years. My feet were always wet. I saw things…”

He stopped then and almost smiled. I only saw sadness.

“All I wanted all that time was a warm, clean, quiet place to sleep,” he said. “There is nothing heroic about war. I hope to God you never face anything like it.”

I thought I saw tears in his eyes, but he turned away and got another beer from the refrigerator. It was Burger beer. He liked Burger beer and Old Grand Dad, but he didn’t discriminate.

When I would ask my dad about World War II, he would rather have talked about Ted Williams, “The grandest hitter the world had ever seen.”

For a living, he drove a big Auto-Car across the country. He changed his socks three times a day. In the trailer where he lived, there were stacks of blankets at the foot of his bed. They smelled like fresh air and sunshine.

My grandfather—we called him Pap—was a handsome man, who smoked a pipe and restored old clocks and watches. He called them “time pieces.”

He told me about the Depression: people starving and begging and turning to crime, respectable people—neighbors. He was in college back then, studying at Richmond, Kentucky. He wanted to be a teacher or a lawyer. His dreams died on Black Monday. He ended up getting work where he could: driving a huckster wagon, delivering mail; working the fields for more prosperous farmers.

“I remember working for a dollar and a half a day and glad to get it,” he said, loading and tamping the pipe I loved to smell. “But we were better off than most. We had our gardens and our stock, and we made a little and traded a little.

“Times were hard,” he said, smiling—he was always smiling—“but, as it turned out, things worked out. We were fine. “

Moeller Brew Barn wishes to thank loyal clientele for your support during the mandated closure of restaurants and pubs. See you again, soon.

My mother and I moved to town when I was starting high school. My neighbor was Mr. Keene, Mr. James Keene. I thought the world of him.

He was an older gentleman, a widower, who liked to sit on his porch in the summer and read books or listen to ballgames on radio.

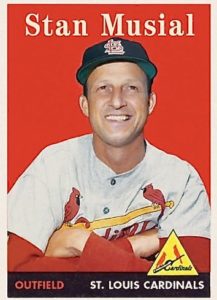

Mr. Keene was an older gentleman, a widower and veteran of World War I. He was also a Cardinals fan.

He was very quiet, sad, I think, being alone. He told me he liked it when I would come over to talk. He liked, baseball, too. He was a Cardinals fan. He told me stories about the Gashouse Gang, Dizzy and Daffy Dean, Pepper Martin, Ripper Collins and Ducky Medwick.

“Leo Durocher was full of himself,” he said, “but he was a plucky player. I’ll be damned if he wasn’t.”

Mr. Keene was a veteran, too, a veteran of World War I. He wasn’t in Europe long. I asked him if he had been wounded. “No,” he said, “but I nearly died—of the flu.”

“The flu?” I said.

“Yes,” he said, looking way off, as if he’d spotted something distant. “It took a lot of us. I was lucky.

“The flu killed more people than died in the war,” he said. “I was sick for weeks and weeks. I’m not even sure how long I was sick.”

Of the US soldiers who died in Europe, half of them fell to the influenza virus and not to the enemy. It’s estimated that 43,000 servicemen mobilized for WWI died of the H1N1 virus.

The Koverman-Staley-Dickerson agencies remind everyone to stay positive and be safe during the current Covid-19 emergency.

“It was terrible,” he said, “worse than the mud and the shelling, worse than I can describe. But,” Mr. Keene said, turning away from that memory, “I met Mrs. Keene when I was in the hospital back here in the states.”

They had been married nearly 50 years when she passed and, I’m sure, they were the happiest years of his life.

I have heard stories of trials and tragedy as long as I can remember, but always there was a greater, more important one; those about resilience and strength and enduring what comes one’s way.

One day when I was in college and more concerned with the Vietnam War than my British and American Literature class, I got word that Mr. James Keene had died. I lost a little something that day. I lost a little something when they all passed: Dad and Pap and so many others.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that my family, their friends, were fighters – stronger people than we are today.”

I’ve come to the conclusion that my family, their friends and neighbors were fighters, people of strong stuff, people of pluck, who took care of themselves and one another. Stronger people than we are today.

Now, I shall think of them everyday and the little lessons they offered.

I will think of Pap who always said, “Be smart, son. Be smart.”

I will think of Dad, who on those rare occasions when we talked, always said, “Stand up, boy. Be strong and act like somebody.”

Mostly, I will think of my mother and know that each time I talk to her is a gift and each time she will say the same thing, the same kind of thing, she has said for years:

“Buck up, son. We’ll be just fine.”

Of the US soldiers who died in Europe, half of them fell to the influenza virus and not to the enemy. It’s estimated that 43,000 servicemen mobilized for WWI died of the H1N1 virus. - Greg Hoard (Press Pros File Photos)