As the World Series plays out, Press Pros’ Greg Hoard shares a story of his baseball journey from the backwoods of Indiana to the backstop at Yankee Stadium.

Cincinnati, OH – Noise.

Cincinnati, OH – Noise.

It was everywhere, an endless din. It was inescapable. It was pervasive. It was profound. It roared in from the Van Wyck and spilled down from the 161st Street subway station.

People spoke loudly in New York for good reason—to be heard, to demonstrate their existence. Otherwise, they were lost, awash in nameless obscurity. If the meek shall inherit the earth, New York is surely out. Some one best check the fine print.

It was October 26, 1996, Game 6 of the World Series, New York Yankees and Atlanta Braves. I was leaning against the short fence behind home plate at Yankee Stadium.

Al Leiter, formerly of the Yanks, then with the Marlins and trying his hand as a TV analyst, stood beside me watching batting practice, watching fans rush toward their seats, push at the fences. It was more than two hours before first pitch and Yankee fans were intoxicated with that odd mix of anticipation, excitement and anxiety.

New York stood one game away from claiming its first World Series since 1978. The Yankees, historically the lords of the game, had not appeared in a World Series since 1981. This night, they could end the 15-year drought that fueled the energy already palpable in baseball’s most hallowed cathedral.

“Man,” Leiter said, his arms folded across his chest. “Ain’t this something. Ain’t this something.”

He was speaking very loudly. He knew the drill. Three years he had played with the Yankees and lived in New York—1987 thru 1989.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Yeah, man. New York. The World Series. Yanks with a chance to take it. Ain’t nothing like it. Never will be. Know what I mean? Just look around, look at these people—wild—and a pitch hasn’t even been thrown yet.”

I nodded and smiled.

“It’s good everywhere,” he said. “But it’s just different here. This is it, the Mecca of baseball.”

He laughed then. It was more of a chuckle, as if the words, the very thought, was a contradiction of character.

“Listen to me,” he said. “‘The Mecca of baseball.’ Jeez. That’s deep. Too deep for me.”

I was standing on the same ground where my heroes and idols stood…Mantle, Maris, Dimaggio…and the Babe!

Just then a young man rushed toward Leiter. He was nervous, almost frantic. On a cool night he was sweating profusely. “Al, there you are. I been looking all over for you, man. We got stuff to do. I’m producing your segment. Come on, we gotta go.”

Leiter gave the man a wary look. “Calm down,” he said, extending his hands palms down toward the producer. “Easy, easy man. It’s not going to help anything if you have a heart attack.”

Sometimes the job, any job, will eat you up. As they walked away joining the throng assembled on the field to cover what very well could be the deciding game, I realized that I had allowed the job to take its toll on me, as well.

Geez, I thought, how many World Series have I covered, 17 – 18?” I had never really thought about it before. For a moment, I was ashamed. A man gets the opportunity—the privilege—to cover an event like the World Series and he just takes it for granted. Good Lord.

Just days earlier I had been in New York for games one and two of the series and I had gone about things as if it was simply another day on the job, though I had never before been to Yankee Stadium.

I had been trying to set up an interview with Paul O’Neill, the Yankees left fielder and a leader on the team. I had known Paul since the days when he broke in with the Reds. I wanted to talk with him about how he had blossomed in New York putting some bad blood that existed with the Reds—specifically with managers Pete Rose and Lou Piniella—behind him.

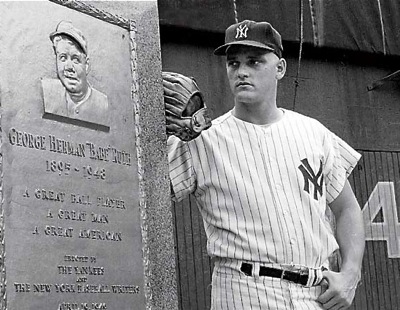

Roger Maris in “monument valley” of old Yankee stadium, with the statue of the icon whose record he broke in the summer of ’61…Babe Ruth.

But just then my mind drifted away from work. Suddenly, I was seized by the fact that here I was—a kid who had come from farm country in the middle of nowhere—standing on the same ground, in the same place, where my idols and heroes—and those of so many others—had walked and played: Mantle, DiMaggio, Gehrig and Ruth; and all those who had come to play against them: from Ty Cobb to Ted Williams, from Roberto Clemente to Warren Spahn and Sandy Koufax and on and on and on.

It was as if I had abruptly awakened from a far-fetched dream. I stood staring at the ground. Who else, I ask myself, had stood right here? How could this be? How was it that life had led me to this place?

As a boy Yankee Stadium was, indeed, the kingdom. It was what we all aspired to. Each day we had gathered at some field, some pasture, a patch of black-top to play ball, to trade baseball cards and dream—dream so hard—of playing at Yankee Stadium, just maybe being good enough some day to wear the pinstripes.

It was a world so far away from our own, from the tobacco patches and cornfields, the gravel roads and Colwell’s General Store where we scraped enough change together to buy a pack of baseball cards and root beer, where we’d sit on the porch until Mr. Colwell or his wife would shoo us away, sounding just alike: “Don’t you boys have something you best be doin?”

I looked past the cameramen and reporters who milled about foul territory and, still immersed in my reverie, walked toward the on-deck circle that was roped off and protected from all but the players, still going about their pregame rituals.

The timeless photo of Bill Mazeroski hitting another “shot heard ’round the world” in the ninth inning of Game 7, 1960 World Series.

I gazed at the Yankee logo and remembered the day my best friend, Sammy Campbell, sat down in the grass and cried because Bill Mazeroski had hit a home run in the ninth inning at Forbes Field to beat his beloved Yanks. It was 1960. Sammy was 11 years old, two years older than me. He had tears in his eyes and the Yankees team card in his hand.

“The Pirates?” he said, between tears. “Mazeroski? That can’t be, can it?”

He was inconsolable. He cried harder that day than the day he crashed a bike into the railroad tracks, cracked a front tooth and darn near broke his jaw.

Standing there by the on-deck circle I thought of all the boys back home: Sammy and Shep, Pete, the Stutsman boys, little Gary Robinson and Dave Crane, all of us who’d shared the big league dream. But none had reason to dream harder than Sammy and none dreamt harder.

I wondered where they all were. I had heard, it seemed, that Sammy had passed. I hoped it wasn’t so. I wished—though it was foolish—that somehow they could have all been there with me, especially Sammy.

For a long time he was the best ballplayer among us. Sammy was one of seven kids. Once I ate lunch at his house down by the railroad tracks. We crowded around the table for saltine crackers with mayonnaise, canned tomatoes and sweet tea.

Sammy would do chores for neighbors to make a little spending money. He spent it on Twinkies, pop and baseball cards.

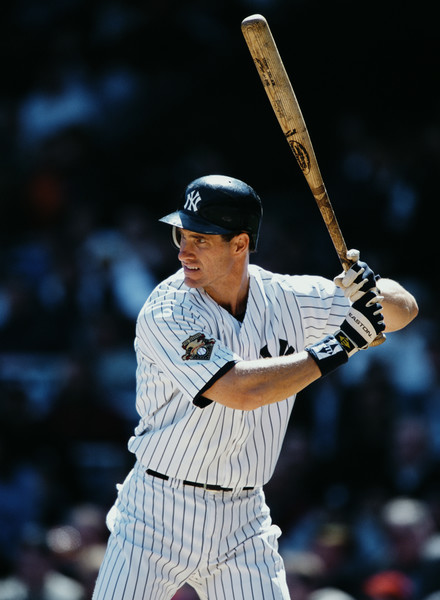

Paul O’Neill as a Yankee…was another regrettable trade by the Reds, who received Roberto Kelly in return.

He loved the Yankees. He wanted to be a Yankee. Above all else he wanted a life that was more than saltines and mayonnaise for lunch.

“Gotta move back now. Time to clear the field.” My memories were jarred by reality. Security guards were beginning to herd reporters off the field.

“Step it up, fellas. Let’s go. Party’s over. Time to play ball.”

We fell in line and headed for the tunnels, dark and dingy and showing their age. The old stadium had seen better days.

That night the Yankees beat the Braves, 3-2. They scored three in the third and hung on. When Charlie Hayes caught a pop fly in foul territory just beyond third base for the final out, the stadium erupted in a roar of joy that was unimaginable.

They know how to party in New York and they love their Yankees. It’s a love that has been handed down from one generation to another. So, they stood. They stomped. They yelled and cried.

Grandfathers danced with granddaughters and grandsons. Strangers danced and cried and laughed with strangers. This was happiness, a happiness long absent and long coming.

Former Reds beat writer Greg Hoard writes baseball nostalgia for Press Pros Magazine.

They stood. They stomped. They yelled and cried, wailed and laughed. They danced where they could and ran where they couldn’t. They kissed and hugged and yelled some more and all of it wrapped in Frank Sinatra’s New York, New York piping from the stadium sound system so loudly it was nearly impossible to understand anything anyone was saying, and it really didn’t matter.

I had seen celebrations, but nothing like this. This was like the old films of VJ Day. The only thing missing was the sailor smooching the gal in the middle of the happy chaos.

The game had taken two hours and 52 minutes and it seemed the party would last longer than that. The security staff had succumbed to the celebration.

True to his word, O’Neill re-emerged on the field for our interview. He was drenched in champagne and, I do believe, the happiest man I’d ever seen in my life. There were no bounds to the smile on his face or the joy in his eyes.

Amidst it all we had a good, long talk but always O’Neill returned to one topic. He would look around clearly trying to savor every aspect of the experience.

“Everyone should see this, experience this,” he said, over and again. “I feel—I don’t know, I don’t quite know how to express it,” he said.

“Privileged?”

“That’s it,” he said. “Exactly. So many play this game, dream of playing this game and they never experience something like this.

“Makes you think about things. You know, things bigger than you and me, bigger than all of else.”

He smiled as if he was almost embarrassed by even broaching such a topic. “You understand what I’m saying, right?”

“I sure as hell, do, Paulie,” I said. “I sure as hell do.”

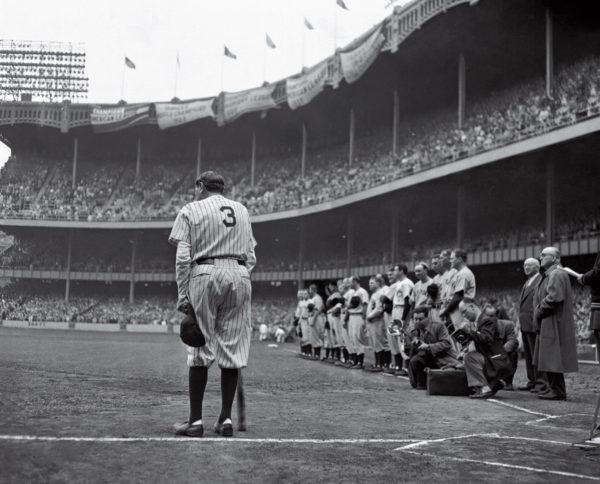

It was the house that Ruth built...and where the iconic Yankee slugger made his farewell speech on June 13, 1948, just weeks before he died. (Press Pros File Photos)