A controversial star and misunderstood for his time in Cincinnati, Frank Robinson (Robbie) had the last laugh on one of baseball’s worst trades…and on those whom he felt had treated him badly.

CINCINNATI — The sun was sliding down behind the western rim of Riverfront Stadium. Slender shadows were beginning to stretch across the field and with them came a cool and welcome breeze. It was a grand day for a baseball game, early enough in the season when all had a chance and everyone was hopeful—realism be-damned.

CINCINNATI — The sun was sliding down behind the western rim of Riverfront Stadium. Slender shadows were beginning to stretch across the field and with them came a cool and welcome breeze. It was a grand day for a baseball game, early enough in the season when all had a chance and everyone was hopeful—realism be-damned.

The Giants were in town and their young guns—Jack Clark and Chili Davis—were putting on a show during batting practice. The powerful Clark was shooting for the upper deck.

“Ain’t gonna reach those Red seats, Jackie Boy,” Davis said. “Not gonna happen.”

“Only way you’ll get there, Chili, is you go buy a ticket,” Clark said, puffing the words out between swings.

“Yep, nothing like those five o’clock hitters, Jackie Boy,” Davis said, smiling. “I know you got your membership card. See how you do come game time.”

My job early in the ’82 season was to find a good feature from the visiting clubhouse during each home stand. I was trying to decide between a story on Clark or Davis when I felt a friendly hand on my shoulder. I knew who it was before I turned around. Earl Lawson had an affinity for expensive colognes, subtle and sophisticated.

Earl, of course, was a living legend, the baseball writer for the Cincinnati Post, whose work and name was known across the country, from the pages of The Sporting News to Harper’s and Colliers. By the time he took me in charge, he was a grizzly 60-some and headed for the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame. A man couldn’t have had a better mentor and guide into his profession, and I remain thankful to this day.

“Come on, kiddo,” he said. “Somebody I want you to meet, get to know.”

His speech was spare, just like his copy. An Earl Lawson story was like a Dragnet script. “Just the facts, Ma’am…Just the facts.”

“Who we seein’?”

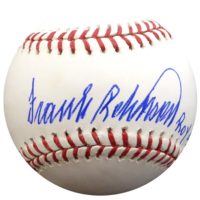

“Robbie,” he said, smiling. “Frank Robinson, my old friend. Maybe, after all this time, he will give you an autograph.”

Frank Robinson in the winter of 1965 for Milt Pappas, the worst trade in Reds’ history.

Earl laughed real big at this little jab. I had told him my stories about chasing Robinson through the players’ parking lot at old Crosley Field when I was a kid—time and again—and never getting him to sign my scorecard.

“Until finally,” Earl said, recalling my tales, “you corner the SOB at a Royals game at Cincinnati Garden and he gives in ‘cause you got him trapped and you are bringing a crowd. I love that story. Diligence pays, my friend, Diligence pays.”

“And by that time,” I said, “I had grown up a little and his autograph didn’t mean that much to me.”

“It’s the way things go sometimes,” Earl said. “Hell, you’ll like him. So much of Frank is a front. Always has been. ‘Course, I’ve told you about that.”

My first months on the job I spent hours talking with Earl, asking questions, quizzing him on one player after another from Don Hoak and Solly Hemus to Stan Musial and Jackie Robinson, not to mention the current stars.

Earl started his career in 1949. He was a tough bird, a veteran of World War II, an infantryman in the Pacific Theater. He fought at Corregidor. He defended his country. Back home, he defended his honor. He fought with Rodgers Hornsby. He slugged it out with Johnny Temple. Several times Earl and Vada Pinson came to blows.

But Earl and Frank Robinson were friends, dear friends. There were some former players who openly disliked Earl. “But,” former Reds catcher Ed Bailey once told me, “you ain’t gonna find any who don’t respect the old bastard.”

My impression of Robinson was based largely on brief encounters in that dark parking lot at Crosley. He struck me as cold and distant, pompous and parsimonious. Of course, I was one of a swarm of little guys who chased Robinson to his car night after night. Most of us begged, but some clung to his coattails and some cursed him when he rebuffed their requests—their demand, in some cases—for his autograph.

The hardest part was that Robinson did sign for some kids. He signed for black kids, but not often. Sometimes there was a gift—a ball or a bat pulled from his trunk. We noticed and grown-ups noticed and sometimes things were said. They weren’t pretty, and everyone heard. Robinson heard. A night at the ballpark became uncomfortable. Earl had heard that part of the story, too.

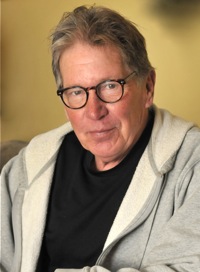

Earl Lawson was my mentor as a young writer, and a friend of Frank Robinson’s…a dear friend.

“You have to remember,” Earl said, one night over drinks, “things here were not easy for Robbie. In fact, that’s basically why he was traded.”

I pushed Earl for details and, at first, he was reluctant to elaborate. But I kept after him, saying the trade simply didn’t make sense.

His eyes settled on me as if he was wondering if I was worth his trust. He lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply and said, “Robbie liked a good time, and he liked women—didn’t matter what color. It made a lot of difference to some people here in Cincinnati.”

Over the years, there had been several incidents in bars, restaurants and cocktail lounges, and several times police had been involved.

Eventually there were rumors that Robinson was carrying a gun for his own protection and then came a phone call in the middle of the night. Earl had just settled into bed.

“It was Robbie,” Earl said. “He was in jail. He said, ‘Earl, can you come bail me out.’”

There had been an incident at a late-night hash house with a short order cook and several of the patrons. Earl was surprised to get Robinson’s call.

“Normally,” he said, “things like that were handled by the traveling secretary or somebody with the club. They wanted to keep it out of the papers. But Robbie said he had made a couple calls and nobody was coming. They were tired, Robinson said, of the whole matter.

“And that, was that. Robbie was never happy after that. I think he wanted out from that point on and Bill DeWitt (the owner) was getting pressure in the community to move him. Here’s the thing. Apparently, they asked him something like if he could stick to his own kind, and Robbie laughed at ‘em. Of course, you know what they meant and you know the rest of the story.”

The Reds received pitchers Milt Pappas and Jack Baldschun, and outfielder Dick Simpson. Robinson was the American League MVP in 1966, his first season with the Orioles, and was the Birds’ World Series MVP after they beat on the LA Dodgers.

He was seated at his desk when we arrived at his office door. Robinson pulled himself from his chair when he saw Earl. The greeting was genuinely warm as Robinson wrapped those long arms around Earl and guided him to a chair near his desk.

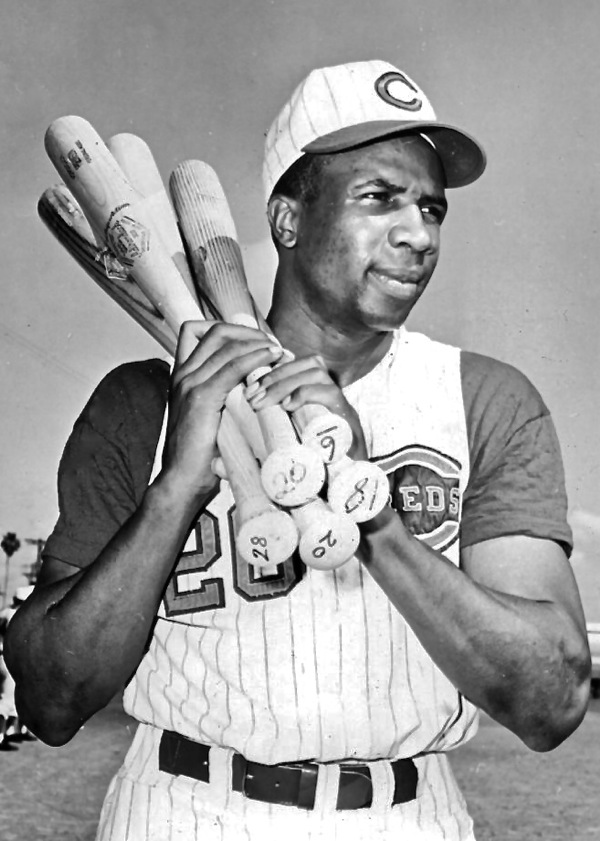

Pictured here in 1970, Robinson led the Orioles to their first World Series title in 1966 and won the Triple Crown that same year.

Earl struggled to find an opening in the conversation to introduce me. Finally, a crack came and Robinson said, “Hey, nice to meet ya,” and with that he was back talking with Earl.

Earl kept trying on my behalf. Finally, as we were getting ready to leave, Earl said, “Yeah, Greg, here, will be taking my place when I retire. Trying to bring him up right, know what I mean, Robbie?”

At that point, Robinson turned and looked me dead in the eye, holding the look for a long moment. Even in that situation he was a fierce man. “You couldn’t have a better teacher,” he said. “That’s for damned sure. He’s fair. If ya learn that and nothing more, you’ll be ahead of the game.”

A couple of times during the home stand I tried to talk with Robinson, always in a group situation. Without Earl, I was another piece of wallpaper.

Clearly, Robinson had experienced deep wounds during the early days of his career. Cincinnati was not exactly a liberal font during the 1950s and 60s, and it was easy to understand that he might have felt that his efforts on the field here were not appreciated and rewarded in kind. Instead, he was basically scorned and ultimately dumped.

Robinson’s doors were closed long ago. Very few were allowed inside.

Greg Hoard is a former beat writer of the Reds for the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Years after Robinson was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Reds honored him, erecting his statue outside Great American Ball Park.

The past few years he was back in town and was recognized by the club. I remember one sun-lit day when team representatives gathered around Robinson and everyone did and said the right things. It seemed like a peace accord had been reached. Robinson smiled and smiled some more and spoke of how much the Reds’ recognition meant to him, and all the while I watched and wondered if the wounds had actually healed—had there finally been enough time?

I hoped so, I really did but I didn’t know. I had no idea. Honestly, as I watched, all I could think about was a grand and singular ballplayer, the same man who refused defeat on the field and—for his own reasons—turned his back on little guys and jogged to his car parked in the darkness at old Crosley Field.

Wounds come in all sizes.

Robinson, as he appeared in the early 60s, was a mega-star with the Reds and the National League's Most Valuable Player in 1961. (Photos Courtesy of the Ewing Collection)