They say that hope springs eternal with spring and the start of another baseball season. But I say I’m too old for hope at this point – I’ll just settle for some of the better memories of the past…and a few laughs.

In the column published this past Monday about Buckeye baseball and some predictions pertaining to the 2019 season, I made a reference to the old film actor Ray Miland, who starred in more than 50 feature-length movies during his 55-year career. One of his best, though not hugely acclaimed, was the 1949 baseball film, It Happens Every Spring.

In the column published this past Monday about Buckeye baseball and some predictions pertaining to the 2019 season, I made a reference to the old film actor Ray Miland, who starred in more than 50 feature-length movies during his 55-year career. One of his best, though not hugely acclaimed, was the 1949 baseball film, It Happens Every Spring.

Actor Ray Miland, as he appeared in 1950……

The film centered on a college professor, Vernon Simpson (played by Miland), who invents a substance that keeps insects away from wood. But after a baseball crashes through his lab window and gets coated in the fluid, Simpson discovers that the ball repels wood. To further his experiment, Simpson later tries out as a pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and becomes a master of a pitch that repels baseball bats, propelling him into the national spotlight as a baseball hero.

I love baseball, of course, but I’ve reached the stage in my life where nostalgia has taken over – where I now watch old movies (not Bull Durham) and think reflectively on the days of my youth, of days playing, and old teammates and characters. One of them wrote to me this week.

To my surprise, I received a Facebook message from my junior year roommate that read, “You and Ray Miland both loaded up the ball,” a reference to my final year as a Buckeye pitcher, in 1974. Lemme share some details.

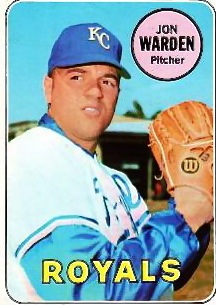

Jon Warden as he appeared with the Kansas City Royals on a 1969 Topps card. He later became a grad assistant coach with Ohio State in 1973.

Midway through my junior season, in 1973, I suffered a shoulder injury that was later diagnosed as a torn rotator cuff. Common, and repairable now, back then it was just a painful prognosis that your pitching days were over. And one day while shagging fly balls in the outfield during batting practice, I was telling our grad assistant pitching coach, Jon Warden, about my miseries…because while I never really threw that hard, I had a great breaking ball, and now even that was gone.

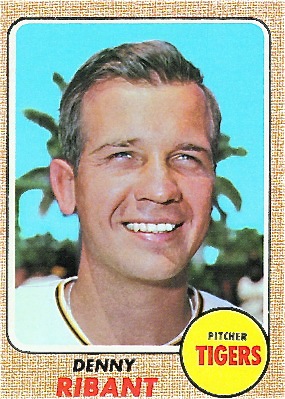

“What you need is another pitch, something different that moves,” said Warden. “Why don’t you learn the Dennis Ribant Sinker?”

Now Warden had pitched with Ribant as a reliever on the 1968 World Champion Detroit Tigers team, and shared with me that Ribant was a master at making the ball sink by methods other than grip. “I can teach it to you if you want to learn,” said Warden. “You kinda’ throw it like your fastball, except you add a little something to it.”

That something turned out to be petroleum jelly, a substance that created a ‘heavy spot’ on the baseball, thereby creating more wind resistance, thereby making it sink.

“It’ll take you a while to learn the release,” said Warden. “But once you do you won’t believe what that pitch will do.”

So, I’d go back to the dorm after practice every day and practice, where Duane Smith, my roommate and owner of an ancient Jim Hegan model catcher’s mitt, was my trusty and devoted backstop. On the lawn outside Stradley Hall each day I’d practice the release on the “Ribant Sinker”, and little by little it began to come around.

Author of the Dennis Ribant “sinker”, Ribant on a 1968 Topps card as a member of the Tigers.

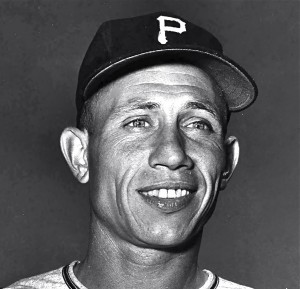

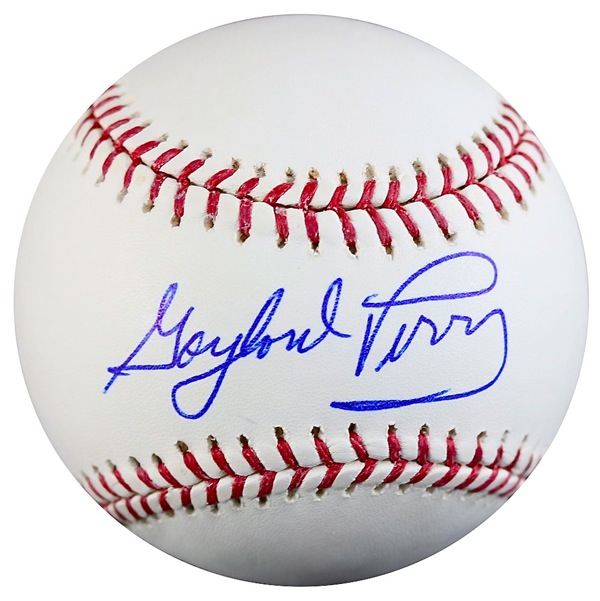

By this time you’ve probably figured out that the Vaseline ball was nothing less than what Gaylord Perry, Don Drysdale, and others were throwing in the major leagues back then, and a pitch that was subsequently banned in 1975. But the more I experimented with it the more I learned and the more fun it became. And while visiting former big league pitcher Harvey Haddix one evening at his home in Springfield, Ohio, he provided the final tip on how to throw it with more efficiency, as well as discreetly.

Haddix had played high school baseball in Springfield with my high school coach at Piqua High School, Jim Hardman. So I had that connection and I can fondly say that Harvey took an interest in me, and my wanting to get back on the mound and compete.

“Don’t use that Vaseline,” he said. “When I was in Pittsburgh Bob Friend really threw a good one and he used KY Jelly, because by the time it gets to home plate it evaporates and you can’t detect it on the baseball.”

KY Jelly, among its other usages, was invented as a surgical lubricant in 1904. It’s incredibly slick, and easy to both hide and apply to a baseball. Haddix, who pitched the 12-inning perfect game for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1959, knew every trick in the book. He altered my grip and release so the ball dragged off my thumb as it slid off my finger tips, creating a kind of tumbling forward spin.

“It’ll take you a couple of weeks to get it,” he said, giggling like a school girl. “But when you do you’ve got something no one else over there has ever seen.”

Former big leaguer Harvey Haddix, from Springfield, taught me the finer points of the best breaking ball I ever threw.

Well, the first time I threw it in a game on our spring trip the following year, someone from the Miami Hurricanes saw it pretty good because it didn’t sink…and he hit it 400 feet. But the next hitter swung at one that looked belt high, only to dip straight down where catcher Terry McCurdy literally caught it in the dirt. Armed with just that much confidence, I was on my way.

No one really had any issues with it, or suspected anything amiss. College umpires had never seen it and I was getting outs with it. And notably, Gaylord was getting wonderful press at the time for his throwing it in Cleveland, even though he claimed he didn’t. The following year they changed the rule that allowed any kind of foreign substance on the ball – even wetting your fingers to get a better grip.

Marty Karow, however (OSU’s coach at the time), was not on board and swore that he would not allow me to pitch as long as I was playing by my own rules.

But Marty also liked winning like Donald Trump likes Twitter, and late in the my senior season we were playing Michigan State in the second game of a Saturday double-header. On that warm May afternoon Karow informed me that I would get the start against the Spartans…because we were out of pitchers, simple as that.

It didn’t start out well.

My last appearance as a Buckeye, a 7-5 win over Michigan State in May, 1974.

Trying to get by with a mediocre fastball and a high school curveball, the MSU hitters ripped one line drive after another in the first inning and before I knew it we were down 5-0 and Marty was on his way to the mound.

“He doesn’t have a thing,” he said about me to McCurdy, who was catching that day. And then looking me squarely in the eye, he added, “If I were you I’d throw that good sinker you’ve been working on.”

So what the hell…we did. And for the next six innings Sparty got exactly no runs on three hits, struck out six times, and the Buckeyes scored seven to come back and win the game, 7-5. As it turned out, it would be my last college appearance, and my last win of any kind in organized baseball. When it was over Jon Warden laughed so hard in the dugout I feared he’d break a rib. And Marty Karow gave me a big bear hug as I crossed the foul line after the final out.

Hence, the reference to Ray Miland and the movie; and to Duane Smith, who reminded me that like Miland, I owed it all to chemistry. But that’s not true.

The ones I really owed were ‘Coach’ Jon Warden and Harvey Haddix; and Johnson & Johnson, of course.

The things you remember at my age…on opening day!

A prized possession and memory...Gaylord Perry signed this baseball at old Cleveland Stadium in 1974. (Press Pros File Photos)