To most, a baseball bat is just a bat, but others beg to differ. There’s aluminum, and there’s wood. And the local Ohio company in Plain City that specializes in only wood bats would differ even more. There’s no wood…like Phoenix wood.

PLAIN CITY, Oh — To most professional baseball players, a baseball bat is not just an inanimate object that is dragged to home plate.

PLAIN CITY, Oh — To most professional baseball players, a baseball bat is not just an inanimate object that is dragged to home plate.

To most, it is life its ownself, a live, breathing soulmate to be loved and caressed, to be protected with a Magnum .357, if necessary.

Hall of Famer Ken Griffey Jr. spent hours before games sitting on a black steamer trunk in front of his locker, checking several bats to make sure the feel was perfect, keeping some and discarding some, making certain they felt exactly right in his hands.

After games, he polished his game bat, removing the marks baseballs make when contacting the bats, “So I know after each game that I was making square contact.” And nobody, but nobody, touched his bats.

To Yasiel Puig, the newest Cincinnati Reds outfielder, his bats respond to his personal attention. Between pitches, he talks to his bat and gives it French kisses, licking the barrel.

“If there is something good to hit and I miss it, I lick my bat, or I try to talk to my bat like, ‘Hey, if you can give me something good right in this moment,’ he listens to me,” said Puig.

“I believe that is so and the next pitch, I hit a home run, or I put my team winning,” he added. “That’s a reason I do lick the bat, but I don’t like it.”

Maybe a little strawberry flavoring would help.

Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn sometimes tucked his bat under the covers next to him at night.

Phoenix Brad Taylor gives McCoy and Press Pros associate Jim Raterman a tour of the ‘billet’ storage room.

“To cure a batting slump, I took my bat to bed with me,” he said. “I wanted to get to know my bat a little better.”

Hall of Famer Lou Brock was known for stealing bases, but he realized he couldn’t get on base without a trusty piece of ash in his hands at home plate.

“Your bat is your life,” he said. “It’s your weapon. You don’t want to go into battle with anything that feels less than perfect.”

And that brings us to a little corrugated building on the outskirts of Plain City, between Springfield and Columbus, home of the Phoenix Bat Company.

The company began in the garage of Charlie Trudeau in 1996, sort of a hobby. He hand-made five bats a year in his detached garage in nearby Hilliard.

He eventually hired a college student at Ohio State, Joel Armbruster, his first employee, “To work once a week. Soon I was working seven days a week,” he said.

The company moved to Plain City in 2004 and Armbruster is now the company’s CEO, and Phoenix turned out 20,000 bats last year.

It isn’t Louisville Slugger, which makes 1.3 million bats a year, but Phoenix gives each bat personal and loving care and the company is growing as word spreads.

Brad Taylor selects from a rack of billets for the turning of a Phoenix pro model bat.

It all begins in a room that resembles a humidor, but instead of cigars the climate-controlled room, 30 percent humidity, is filled with long blocks of ash, maple or birch weighing more than 85 ounces. For example, one 87-ounce block of birch is lathed down to a 33-inch bat that could hit a game-winning home run in the summer Cape Cod League. And the room smells better than a lit Cohiba.

The wood is taken to an Italian-made machine, a ‘Locatelli’, which doesn’t make Italian loafers. It was designed to make table legs, but has been transformed into turning those blocks of wood into baseball bats.

Phoenix has the only Locatelli in the world that cuts the bats and sands them at the same time, a process that takes two minutes.

The company is 100 per cent green, not a single shaving off those blocks of wood is wasted. There is an Amish furniture store down the street that takes all the sawdust and area horse and cattle farms take the shavings.

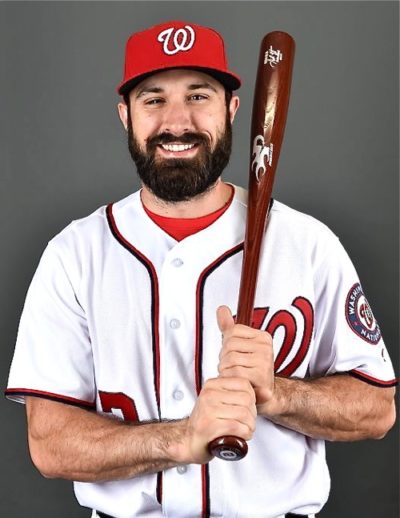

Phoenix makes 674 different models, 29 to 36 inches in length. The better bats are game-used by summer college leagues, which still use wood bats, and by major leaguer Adam Eaton of the Washington Nationals, who grew up nearby and attended Kenton Ridge High School.

Washington Nationals outfielder Adam Eaton and the tool of his trade…a Phoenix bat.

He uses ash, one of the few who still do because due to disease the ash tree is fast disappearing and may be gone in a few years. Phoenex has about a year-and-a-half’s supply on hand.

Other bats are used by colleges as teaching tools, Little League teams and as promotional trophy and decorative trinkets that hang on walls.

They come in all colors of the rainbow and then some — black, maroon, gray, purple, fuschia — whatever the customer desires.

Brad Taylor, Phoenix’s director of professional sales and designer, says some Latin players have toured the facility, “And they are blown away by the process. They had no idea how bats are made and the steps that are taken and the care that is taken to make one.”

Of wood bats over aluminum, Armbruster says, “A wood bat never lies. A bad hitter can be a .300 hitter with an aluminum. A .412 college hitter using aluminum might hit .212 in a summer league using a wood bat.

“But he might hit .312 with a Phoenix,” he said with an impish grin.

While Louisville Slugger is the ‘name brand’ and Armbruster says, “We’re not there yet,” his vision is to be like Marucci, a Louisiana-based company that has the most major leaguers using its bats.

While Louisville Slugger is the ‘name brand’ and Armbruster says, “We’re not there yet,” his vision is to be like Marucci, a Louisiana-based company that has the most major leaguers using its bats.

“Their business-model is that they have players invested in their company, like one or two percent,” said Armbruster. “David Ortiz is an owner and he swung Marucci and he could say to other players, ‘Hey, here are a dozen bats, try ‘em. And Mookie Betts is a part-owner.”

Hall of Fame pitcher Lefty Gomez once said, “I was the worst hitter ever. I never even broke a bat until my last year when I was backing out of the garage.”

He needed a Phoenix. Even a car backing over one won’t break it.

Stacks of maple, ash, and birch billets will eventually become one of 674 different Phoenix bat models.

Bats for every occasion, including ‘fungos’. Phoenix is proud to support Buckeye baseball on Press Pros.

Phoenix CEO Joel Armbruster proudly shows Hal McCoy one of their models as it leaves the lathe (background). (Press Pros Feature Photos by Sonny Fulks)