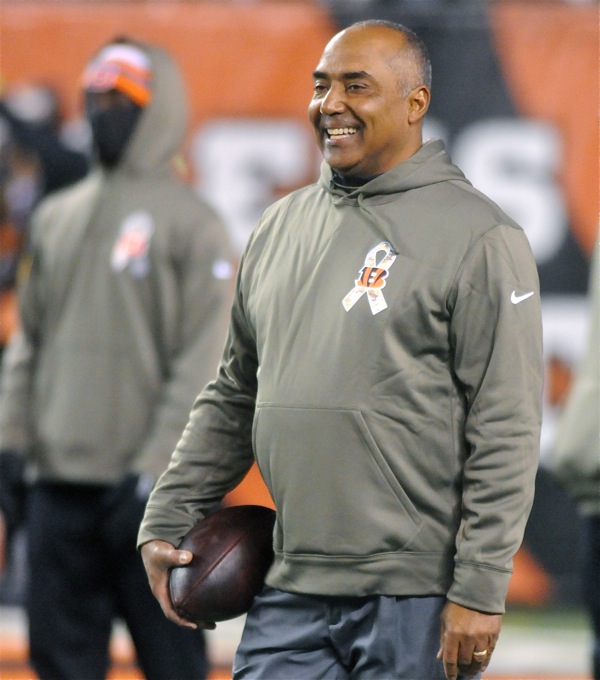

I was there at the beginning, and I was still around to witness the end of the Marvin Lewis era with the Cincinnati Bengals. There were questions as to who was in charge then, and in the end…there were still more questions than answers. It seems there always is with the Bengals.

CINCINNATI — First, he was solemn. Then, after a prolonged silence, he leaned back in his chair, crossed his legs and smiled.

CINCINNATI — First, he was solemn. Then, after a prolonged silence, he leaned back in his chair, crossed his legs and smiled.

“Yeah,” he said. “Yeah, it’s my team. I will make the decisions.”

It was the summer of 2004, a long way from Monday morning when it was announced the Bengals had parted ways with Marvin Lewis, their coach of the past 16 years.

Lewis was in his office at Paul Brown Stadium back then preparing for his second season as coach of the Cincinnati Bengals. He was energetic, thoughtful, engaged.

He had debuted with a modest 8-8 performance, but that was ice cream and cake after what had been dished-up here before his arrival. From 1998 through 2002, the Bengals were 21-59. Their fans had been numbed—driven to varying degrees of indifference—by successive seasons of 3-13, 4-12, 4-12, 6-10 and 4-12.

These pitiable performances came with Bruce Coslet and Dick LeBeau as head coach. Both men had a solid relationship with the press and each suggested, at varying times during their tenure, that the Bengals problems went well beyond the man in the first chair.

They hinted that their hands were tied in many instances, including who played and who didn’t. There were other intimations. Chiefly:

They didn’t have as many scouts as other NFL teams. Their assistant coaches were underpaid and overworked. There was no general manager to act as a buffer between ownership and the front lines. Consequently, things fell through the cracks. Losses mounted.

The list went on, all of it pointing toward team president Mike Brown and all of it, as you might expect, off the record.

But when these questions were raised—and they were—they were summarily dismissed by Brown. They were words, he said, of frustration and disappointment, lacking in truth in some cases. He dismissed any rift with his coaches or any leashes on their actions.

LeBeau was fired after a 4-and-12 in 2002, and for the first time in team history, a coach was hired from outside the Bengals’ family tree of coaches.

So, back in 2004 on that summer day in Lewis’ office, the question stood: “Who is really in charge?” He insisted that it was a new day that it was his team. I don’t know what it was like before, he said, but things will be different.

We had spent the better part of two hours talking about his place here and his responsibilities, and Lewis never wavered. He was here to do a job and improve the situation, he said, and he would get the job done.

As we left his office, walking down stairs toward the locker room, he offered one caveat. “It’s a process,” he said. “It’s a process…It’s not going to happen over night.”

With that he opened the door to the locker room. Uniforms were strewn about the place, tape and towels thrown to the floor. It was hours after practice and the place was a mess.

Lewis looked around. He was clearly embarrassed, like he had invited a guest into his home and the sink was stacked with dirty dishes and empty beer bottles lined the counters.

“Like I was saying,” he said. “It is a process.”

That season, his second, the Bengals were 8-8 but in 2005 they went 11-5 and earned a spot in the playoffs for the first time since 1990. It closed a run of 14 years when the Bengals were 71-153 and had not sniffed the playoffs.

There was dancing in the streets until Kimo Von Oelhoffen rolled up on Carson Palmer’s knee, ending his day and, some still insist, altering Palmer’s future and the future of the team.

It appeared that Lewis had the Bengals off and running, but that wasn’t the case. They would reach the playoffs six more times and six times they would lose.

The last of those—2015, again against the Steelers—was an embarrassing display in an utter lack of discipline and self-control. The leaders in this meltdown were Vontaze Burfict and Adam “Pac Man” Jones, who jointly cost their team the game.

In the last 18 seconds a personal foul by Burfict, and another by Jones set the stage for a 35-yard field goal and an 18-16 loss that Jim Nantz of CBS sports referred to as “simply disgraceful”.

Lewis should have been fired that day, the very moment he set foot off the field, but he wasn’t. We should have known then, if we didn’t already, that we were looking at an abnormal situation.

Already, there had been signs that Lewis was not up to the task. He couldn’t handle Corey Dillon or Chad Johnson. They did what they wanted, said what they wanted.

And, of course, there was Palmer, the first round draft choice out of Southern Cal—the quarterback of the future, the “Golden Boy”. After seven seasons here he said, in effect, “Trade me or I’m quitting. Goin’ home.”

He was roundly criticized by fans, but stuck to his guns. He had had enough of football in Cincinnati.

Where else does something like that happen?

Obviously, there were major problems. Whoever was in charge was failing.

That was in 2010.

Fourteen years ago when I sat with Lewis in his office he seemed very confident and self-assured. I wrote what he said but I didn’t believe it, and as time went on I was sure there wasn’t a shard of truth in his words. The sad part was that I think—at the time—he thought he was in charge and that he could make a radical change.

To his credit, he did better the team in some respects. But he was not right for the job. It was a bad choice made worse in that it was not corrected in a timely fashion.

We’ve been calling for Lewis’ head since—when?—2009, at least. Now, it’s done.

But that is no guarantee things will be better. Lewis was not right for the job. I will always believe that. But I will never believe that he was the entire problem.

These muddy waters run real deep. They run all the way up to the executive offices.

Yes, Marvin is gone and where he’ll land, nobody knows. But if you noticed, no one was running around Monday afternoon yelling to the rooftops that a new day was coming.

There will be a few days, maybe weeks of guessing who might be coming this way, and it will surely run toward fantasy: Notre Dame’s Brian Kelly or Clemson’s Dabo Swinney. Could it be—Urban?

There will be a few days, maybe weeks of guessing who might be coming this way, and it will surely run toward fantasy: Notre Dame’s Brian Kelly or Clemson’s Dabo Swinney. Could it be—Urban?

Regardless of who is convinced to take the job here, my fear is that nothing will really change.

There will be bright eyes. There will be words of optimism about a new winning day, turning the page and beginning a new chapter. But little will change and most know why. There’s an issue with leadership—an issue with who is in charge.

Separating with Lewis was long overdue, but what they need to do is reshape and rethink the front office, and somehow I just don’t think that’s going to happen.

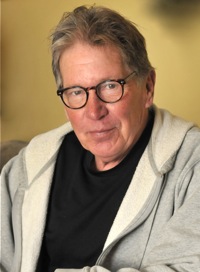

He left as the longest-tenured coach in Bengals history, but to most observers Marvin Lewis's legacy will...it could have been so much better. (Press Pros File Photos)