If you grew up with baseball cards, the story will bring a smile to your face. Once upon a time, in the heyday of Topps, Bowman and Fleer, the competition for cardboard talent at the local store and ball diamond was as intense as the pennant race.

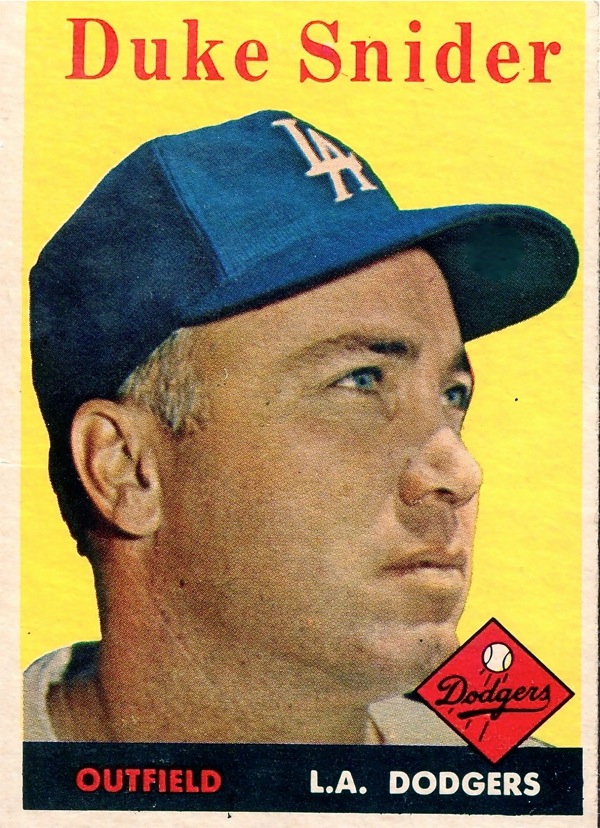

The day I came up with that brand new Duke Snider card the world shifted. A couple of the boys were all worked up, and one of the tough guys started getting all buddy-buddy with me, saying how he and I could work a deal.

The day I came up with that brand new Duke Snider card the world shifted. A couple of the boys were all worked up, and one of the tough guys started getting all buddy-buddy with me, saying how he and I could work a deal.

Understand this was a guy who threatened to whip me nearly every day and a guy who picked fights with younger guys all the time. He was the sort of guy who would spit in your cap, or hide your ball glove over in the weeds—let the air out of your bike tires. He thought this kind of stuff was funny.

He was just tough enough, or acted tough enough, that he got buy with this stuff. The thing I could never figure out was why the guys his age just let it pass.

I was two years younger than the pack, a little big for my age, and smart enough to realize that I had something here in this Duke Snider card that changed the entire picture.

Here was Pete Robbins, skinny as a yardstick, ugly as a rail, all of 11 years old, most days mad as hell at the world and everybody in it, and there he was smiling at me big as you please.

“Yeah, Hoard, what do you want for that Duke Snider card? None of these other boys can make a deal like I can. You know I got the best collection around. So, who do you want? Come on, buddy, let’s trade”

We were sitting on the porch outside Colwell’s General Store, all of us having just dropped about all the change we had on a cold RC and as many packs of baseball cards as we could afford at a nickel a pack. If I remember correctly, RC Cola, wss the last of the soft drinks to make the jump to a dime, so a guy could burn a quarter in a hurry if he wasn’t real careful, and if your weekly allowance was a 50-cent piece you learned conservative economics real quickly. You also understood when you had a fish on the line, and—by damn—I had one, a big one.

Plus, my position was enhanced when Denny Kern, the Baptist preacher’s son, rolled up on his new red Schwinn and decided to enter the bidding war. Like Pete, he was about 11, had more money than most, a good card collection, and a little bit of a mean streak.

“Let’s see,” Kern said, pushing others aside, shouldering up next to Pete.

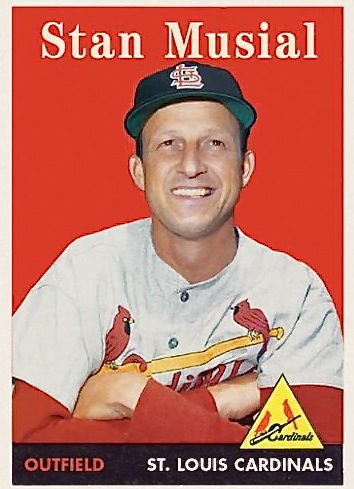

A coveted card of Stan Muisal – 1958 Topps – very rare, and very expensive in this condition.

“I want that card,” he said, turning to me. “What you going to take for it, Hoard?”

He smelled like he’d just come from the barbershop and was dressed, as always, like it was picture day. Boy never had a grass stain in his life.

“Now hold on.” Sammy Jaynes was intervening. “That ain’t no way to talk to Greger.”

Sammy was my best friend. He was the same age as Robbins and Kern, but unlike those two he was poor as dirt. He was one of nine kids. Sometimes they had crackers and mayonnaise for lunch at his house. He was also the best ballplayer in our little town and he had taken me under his wing long ago.

Sammy taught me how to play poker before I could read. I knew a flush beat a straight before I ever heard about Dick and Jane and “See Spot run.”

“Maybe, boys,” Sammy said, “he ain’t gonna trade that card.”

Pete sneered. “He is gonna trade that card, ain’t ya, Hoard.”

Things were changing. It wasn’t all about the card any more. I started thinking this might be the day Pete and I finally had it out, Duke be-damned.

“We’ll see, won’t we Greger?”

Sammy patted me on the shoulder. His presence added a whole lot to my backbone. I just sat there and nodded and smiled.

There were two matters at play:

One, I didn’t really care about Duke Snider. I never believed that he was in the same category as Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle.

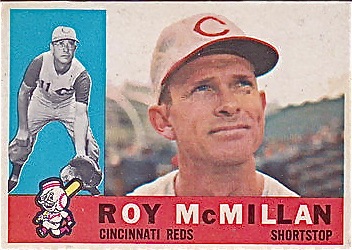

The 1959 Topps set is considered the best looking card of all-time by many collectors.

The cards told the story. Mantle was pure confidence and Mays—like always—seemed like the game just came to him. Snider looked, well, insecure. I liked the Dodgers, especially Carl Furillo, Pee Wee Reese and Roy Campanella, and I knew about Jackie Robinson, but Duke—he just didn’t make it. So, I had that.

Second, I pretty much hated Pete Robbins, and Kern was just a smart aleck who figured he could get by with about anything because he was the preacher’s son and nobody would whip his butt because of that. (He eventually found out he was in error, failing to recognize most of us didn’t go to church.)

So, good fortune had finally turned my way. I had Sammy to back me up in case Pete decided he was just going to try and take the card, which wasn’t beyond him, and I had Kern to drive up the bargaining price.

My confidence soared.

“So, let’s get down to some serious dickering,” I said, biting down on a new stick of bubble gum. “What’cha got, boys?”

For the first time in my life I felt like the man in the room with all the marbles.

Pete pulled some rubes out of his back pocket, Willie Jones, a Phillies infielder, the best of the lot. Kern’s first gambit was a ’57 Bob Clemente, but in those days Clemente had not yet entered the collective consciousness of little guys in southern Indiana. But Kern pulled way ahead when he tossed out a near perfect Billy Cox, a ’54 Bowman.

“Gonna have to up the ante,” Sammy said. “’Pete, you ain’t in the game.”

With that, Pete jumped on his bike and rode home to improve his trade stock and Kern followed suit. That alone was a win.

I had most of the big names, already, and a whole lot of the Reds: Wally Post, Gus Bell, Ed Bailey and the rookie Frank Robinson. So I was looking for the guys who, as my dad put it, “made a team, held it together.”

After all these years I have forgotten every turn of the negotiations, but I do remember what that Duke Snider card netted.

A personal favorite…1960 Topps card of former Red shortstop Roy McMillan.

Robbins won the bidding war. He gave up Mickey Vernon, a good hitting first baseman then with Boston; Billy Goodman, a utility guy and a good hitter; and pitchers Curt Simmons and Sal Maglie, both of whom made a name for themselves owning the inside corner.

What turned the deal, though, was cash. Determined to outbid Kern and have Snider, Pete threw in a dime. The cash was Sammy’s idea. Kern immediately folded and, once more, Robbins had his way.

I split the dime with Sammy. He bought a candy bar and I bought another pack of cards.

“You’re mom and dad know you are spending all this money on ball cards?” Mr. Colwell said, looking over his wire-rimmed glasses.

I said nothing. Those cards were a big part of my world back then.

Sammy was eagerly working on a Bit ‘o Honey as I opened the cards. I thumbed through them patiently finding, as fate would have it, guess who?

“I’ll be doggone,” Sammy said. He had a Christmas morning smile. “I’ll be doggone. Let me show him, okay?”

Pete was still sitting on the porch, smug and bragging to the crowd about his big deal when Sammy walked up.

Still sorting through the heroes of my youth….!

“Hey, Robbins,” he said. “Guess what Gregger got with that dime you gave him?”

“Like I care,” he said. He could be as nasty as spoiled milk and rotten meat.

Sammy just smiled. “Oh you will. Lookie here,” he said, holding the new Snider card shoulder high. “How about that, ya SOB?”

Pete looked. Then he glared. For a moment, he was speechless. “I oughta whip your butt,” he said, glaring at me.

It was his answer to everything. He got on his bike and rode off. We all laughed like crazy.

Duke Snider was my first win against Pete Robbins. Another one came a year or so later after I’d grown some. That one was more definitive. Clothes were torn and blood was shed, but that Duke Snider card has always held a special place in my memories—always will.

The card in question...a near-mint copy of the Topps 1958 Duke Snider card. (Cards courtesy of Rare Sports Films)