My dad had had his fill of guns – he was a WWII veteran. But still, he firmly believed that a growing boy should know about them, learn about them, and respect them for what they could do – good and bad.

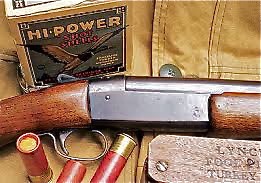

CINCINNATI — On my 10th birthday, my father bought me a 20-gauge single shot Remington. I believe it was a Winchester, Model 37. It was a long time ago. It was 1961.

I wasn’t eager to have my own gun. But it came with the territory. We lived on a 200-acre farm, and all the other boys around did their share of hunting—mostly squirrels and rabbits.

Dad knew I had no great interest in hunting. He knew that I was far more interested in baseball and basketball. Dad wasn’t a hunter, either. He had had enough of guns. He had four major battle stars. He was in the European Theater from 1942 through 1945.

But, he believed that a man—a growing boy, in fact—needed to know his way around firearms. It was weeks before I ever fired the gun.

“There’s a lot to learn,” he said, and there was no give in his voice. I could always tell from his voice and his eyes when I could cut a corner or let something slide.

There was no slack when it came to guns. I knew where he kept his pistol, wrapped in a red cloth and tucked away in the top drawer of his dresser. I knew that he kept a loaded shotgun behind the door in his bedroom.

The rule was clear. I was never to touch either weapon. “You don’t even mention them to your friends,” he said.

I followed the rule, and when my shotgun was unwrapped and out of the box, he said: “First, we learn to put it together. Then, ya learn how to clean it and keep it nice. Later, I’ll teach you how to shoot it. But here’s the first rule: You respect it.”

I remember nodding. I remember my mom sitting across the room very quiet, unsure about the whole thing.

I don’t know how many times we cleaned the gun, or how many times we took it apart and put it back together. I do remember the day we first shot the gun.

I don’t know how many times we cleaned the gun, or how many times we took it apart and put it back together. I do remember the day we first shot the gun.

There was a fence that ran across the back of the yard. It separated the lawn from the woods. It was a woven-wire fence with locust posts. Dad dug around for a while in the wood shed and emerged with some old Maxwell House coffee cans and some rusted one-gallon gas cans.

He’d taught me to aim with my Red Ryder BB gun. That, too, came with rules. I was never to aim it at anyone, and I was never to shoot at any living thing, especially the songbirds that filled the trees around the house.

The shotgun was heavier than the BB gun, harder to steady and aim, so he taught me to sit on the ground and how to rest my elbows on my knees.

“Okay,” he said, opening a box of shells, “now you learn.”

I remember the impact of the gun against my shoulder. I remember the smell and the echo of the shot. I remember Dad smiling and saying, “Hold it snug against your shoulder. Not tight. Snug.”

When I started hitting the coffee cans, they flew back into the brush beyond the fence where the varmints made their homes and played tag with the dogs.

After awhile, he filled a gallon can with water from the well. He sat it on the fence post. “Have at it, boy,” he said, half smiling.

When I hit it, I lowered the gun surprised at what I had seen.

“Break it down,” he said, nodding toward my gun. “I’m going to get the can so you can take a look.”

He came back walking up the small grade with a ripped and torn piece of metal. It was largely unrecognizable.

“See, son,” he said. “This is what a gun can do.”

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t know what to say.

He tossed what was left of the gas can to the ground. “Pretty much a mess, huh,” he said. “We’re almost done.”

He walked up to the back door. I had no idea where he was going or what he was doing. In a few minutes he came out of the house with a watermelon. I loved watermelon and still do. It was then, and still is, one of my absolute favorites. I figured the lesson was over and we were going to celebrate with a watermelon feast.

He walked up to the back door. I had no idea where he was going or what he was doing. In a few minutes he came out of the house with a watermelon. I loved watermelon and still do. It was then, and still is, one of my absolute favorites. I figured the lesson was over and we were going to celebrate with a watermelon feast.

Instead, he walked down to the fencerow. He tried like hell to balance the melon on the fence post, but couldn’t pull it off.

Finally, he just sat it on the ground leaning up against a fence post. “Okay,” he said, back at my side, “load-up.”

I looked at him, surprised. “C’mon,” he said. “Let’s go.”

I dropped the shell in the barrel and readied the gun to shoot. “You set?” he said. “All loaded? Okay, let’s walk a little closer.”

I don’t know how far we were from the melon when he told me to stop, maybe 20 feet, maybe a little closer, but it was a “can’t miss” distance.

“Shoot it,” he said.

“What?”

“Shoot it!”

“The watermelon?”

“Yeah, the watermelon.”

“A waste, ain’t it?”

He gave me that half smile again. “Not in this case. Go ahead. Do it.”

This was difficult for me. We didn’t get watermelon as often as I would have liked. I didn’t like this but I had no choice.

“A little closer,” Dad said.

I looked at him, hoping he would see my doubt about the whole thing and took another step. I took a last look at him and fired.

I couldn’t believe the mess. Dad had flecks of watermelon on his hat and shirt. I looked down at my tee shirt. There were pink pieces of melon on it. I could feel it on my face.

By the post, where the melon had been, there was some rind, some meat—scattered—all over the ground. There were wood splinters from the fence post.

My dad took his cap off and slapped it against his pant leg.

“That, son, is what a shotgun will do,” he said. “Respect that gun. Promise me you will respect every weapon you ever come across. Promise?”

I promised.

I never went hunting, not really. I would walk around in the woods with the gun, but I never fired at a rabbit or a squirrel. I loved to watch the dogs flush quail, but I never tried to shoot into the flock. I couldn’t have hit one anyway. The dogs seemed confused and annoyed with me.

Once in awhile, I would go to the dump on the back of the farm and shoot at rats, but I don’t know that I ever hit one.

Mostly, I cleaned the gun and kept it behind the bedroom door with Dad’s 12-gauge. I spent most of my time shooting baskets, learning how to field ground balls and firing the ball to first.

But I have never lost my respect for weapons and the damage they can do.

I write this now because everybody in the world is talking about guns: what is right, what is wrong, what should be and what shouldn’t.

I write this now because everybody in the world is talking about guns: what is right, what is wrong, what should be and what shouldn’t.

There are no easy answers, none that will please everyone. I never quite know what to say or how I feel when another tragedy occurs and there is so much noise about what’s right, who’s right, what’s wrong and who’s wrong. I do remember those days with Dad and those talks about respect and, of course, the watermelon.

They were good days and good lessons, and I have the sneaking suspicion that Dad was talking about more than respecting the gun. I think—I believe—he wanted me to respect life, all forms of life.

My dad had an eighth grade education. He talked little and never spouted opinion. He’s been gone a long time now, and the older I get the more I miss him. Maybe he could help make some sense of this world.

Our comprehensive selection includes over 1500 guns, a full line archery “Pro Shop”, shooting & hunting clothing, boots, ammunition, reloading equipment, gun cases, holsters and a multitude of other shooting & hunting accessories.

Olde English Outfitters meets the needs of serious sportsmen and casual enthusiast alike. This is truly a store for all your shooting and hunting needs.

Open this year’s hunting season with a trip to Olde English, proud to sponsor outdoors columnist Jim Morris on Press Pros Magazine.com!