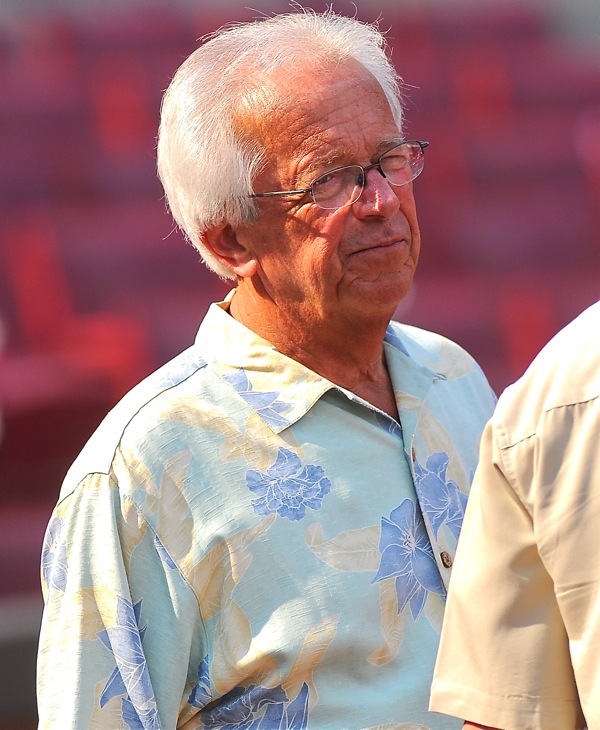

He’s signed through 2018. After that, he is not sure what he will do. He’s 75. The West Coast road trips are becoming more difficult for Marty Brenneman. And one day now we’ll turn on the game and he’ll be gone. It’ll be a hard day…for a lot of people.

Cincinnati – Years ago, he wanted to be an actor. He dreamed of being on stage, living the “pretend” life, enjoying the notoriety, the wealth, the magic Broadway and Hollywood can bestow—overnight.

Cincinnati – Years ago, he wanted to be an actor. He dreamed of being on stage, living the “pretend” life, enjoying the notoriety, the wealth, the magic Broadway and Hollywood can bestow—overnight.

As soon as he graduated high school, he was off to New York. That was the plan, until his mother arranged a meeting with two young actors trying to make their way Off-Broadway, Off-Off-Broadway, anywhere. It didn’t matter.

Work was scarce. Life was tough. A Spam sandwich sounded good.

“These guys were starving to death. Well, it took me about 10 minutes with them to realize I had no stomach for that life, no pun intended.”

At that point, would-be actor Franchester Martin Brennaman chose Door Number Two on his career path, and Marty Brennaman, sportscaster, was off and running.

“There was really no other plan,” he said. “If it wasn’t acting, it was going to be this.”

He is now in his 44th season as the Reds primary radio announcer and, over these many years, he has spoiled legions of listeners. He came to the Reds in 1974 as the club approached the zenith of its history, winning back-to-back World Championships in ’75 and ’76 establishing its place among the greatest teams of all time.

He made his name working with the late and legendary Joe Nuxhall, “The Ol’ Lefthander” and in 2000 was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the profession’s most illustrious achievement.

Over the years, he has had his measure of great and memorable moments, all under the banner of his signature call, “And this one belongs to the Reds.”

But beyond all this, he has done—and continues to do—something even more impressive and more demanding.

During bleak and dreary days for the Reds, he has managed to keep our interest in a ballclub that is hardly worth our interest, and hasn’t been for some time.

The Reds have had five winning teams in the past 28 years. Their winning percentage in the 2000s was .464. In the 2010s, it’s up to .498, and that does not include this year’s showing, thus far another last place performance.

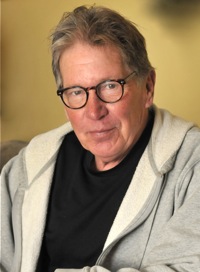

When a team performs this poorly for this long, says Thom Brennaman, Marty’s son and sometime broadcast partner, it is not easy duty.

“It’s very difficult and on multiple levels,” Thom said. “I grew up a Reds fan…In many ways I’m no different than the fan sitting at home watching or listening to the game. I make no bones about it. I want to see the team win. You start out with a series of expectations and then those things don’t pan out. It’s a slow, painful process. When they don’t play well over a period of time, it’s very frustrating—incredibly frustrating.”

But, he adds, you can’t drive it in the ground. “You can’t continue to harp on it. People don’t want to hear that,” he said.

In his 12th season with the Reds, Thom has covered three winning teams (2010, ’12 and ’13). In between he’s admittedly seen some bad ball.

“Now, think about my dad,” he said. “He’s covered some awful teams, I mean beyond description awful…He’s done thousands and thousands of games when the Reds aren’t even in the conversation as a contending team.”

But, such is his talent and our habit that we continue to tune in—even in the worst of seasons—to see, as Brennaman puts it: “How we lookin’?”

To a great portion of the audience this is due to familiarity and trust. There is an ease and evenness about Brennaman’s delivery. He doesn’t whitewash. He doesn’t sugarcoat. But he also avoids overkill.

“I’m constantly reminded of what (Hall of Fame basketball coach) Bob Knight’s wife used to say, ‘That horse is dead, Bob. Stop beating it.’

“That’s one of the greatest things I’ve ever heard,” Brennaman said. “That’s a mantra with me when I start to go off on somebody or the team…

“Whatever I say is not going to change anything, because they are probably playing as well as they can play, and—as often as not—they are playing a team that is clearly better than they are.”

“Ninety-nine percent of the people listening to us are Reds fans,” said Jeff Brantley, Brennaman’s primary broadcast partner. “The last they wanna hear is non-stop: ‘They stink. They can’t hit. They can’t throw.’ They don’t wanna hear that. They want some positive feedback, some semblance of hope.”

After all this time, Brennaman has become the reliable, realistic voice of the Reds. We’ve come to expect him to tell us just exactly how good, bad or hopeless the team happens to be and to do so with balance.

“People constantly come up and say, ‘We appreciate you telling it like it is,’” Brennaman said. “I always say, ‘Let me correct something. I tell you how I think it is because there are times when I have been wrong.’”

During his tenure here Brennaman has gone through multiple stages as an announcer: from young, impressionable houseboy to sage iconoclast.

When he arrived in ’74 he was young (31), impressionable and employed by a team that was coming off a Western Division title. His first season here, the Reds won 98 games only to finish second behind the Dodgers. There wasn’t much to criticize, and Brennaman found himself slipping into a professional trap. He began to think of himself as part of the team.

“We were in Atlanta, I believe, and the Reds had just beaten the Braves something like, 19-6, or something like that,” he said. “The next day I’m talking to (pitcher) Jack Billingham and I say, ‘Helluva game we played last night.’”

Billingham smiled, but corrected his friend very quickly. “He looked at me and said, “‘We? How many hits did you have last night?’ He was friendly about it, but the point was made. I was not a part of the team, nor would I ever be. That’s a select fraternity down there, and always will be.

“From that day forward, I became a more objective broadcaster, and I began to look at the game and how it’s played differently—more professionally.”

One’s stature in the game did not and does not justify slipshod play: the better the player the higher the expectation.

From 1976 through 1978, George Foster was perhaps the best offensive player in the game. The Reds outfielder led the league in home runs in ’77 (52) and ’78 (40), and RBI in ’76 (121), ’77 (149) and ’78 (120). He was the NL MVP in 1977.

Somewhere in this run, Foster had a particularly bad stretch. “I think the worst of it was in New York,” Brennaman said. “He had several bad at-bats, and made a couple of plays that led to runs. Well, I was all over him.”

After the game, Brennaman learned there were mitigating circumstances. Foster was playing with a 102° temperature and against manager Sparky Anderson’s wishes.

“I apologized to George,” Brennaman said, “and I went on the air the next day and said, ‘I was wrong. The man was sick. He had no business being out there in the first place.’”

Brennaman has never employed guerilla tactics as an announcer. He doesn’t hit and run. After all this time Brennaman continues to make a daily pass through the Reds’ clubhouse to ensure that any player who has an argument with him has ample opportunity to confront him.

Brennaman has never employed guerilla tactics as an announcer. He doesn’t hit and run. After all this time Brennaman continues to make a daily pass through the Reds’ clubhouse to ensure that any player who has an argument with him has ample opportunity to confront him.

Everything he brings to the air today is the culmination of experience, so much offered in so few words. The other day the Reds were grinding toward another loss. It was the third or fourth inning and the Reds were already down three or four runs, another was just crossing the plate.

Brennaman said nothing for a moment, just let it settle in on his listeners. “Well,” he said, “when you have next to no offense and ineffective pitching, this is what you get.”

In a few words, he’d summarized not just a season, but seasons—plural.

He is signed through 2018. After that, he is not sure what he will do. He’s 75. The West Coast road trips are becoming more difficult. Time with his wife, Amanda, and his grandchildren is increasingly important.

He is signed through 2018. After that, he is not sure what he will do. He’s 75. The West Coast road trips are becoming more difficult. Time with his wife, Amanda, and his grandchildren is increasingly important.

“The time has not come for me to quit, but I can sure as hell see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Brennaman said. “I don’t know how long it will take to get here, but I can sure as hell see it coming.”

One day we will turn the game on and Brennaman will no longer be there to spoil us. It will be like opening a package and, crud, it’s just not what we expected or it doesn’t quite fit.

It will be a hard day – for a lot of people.

“Yeah,” Brantley said, “we’ve had a lot of talks about that.”